Iconic Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman was born a century ago. His life and legacy are woven into Margarethe von Trotta’s biopic, Searching for Ingmar Bergman, which opens in Toronto at the TIFF Lightbox on December 7.

Bergman, one of the legendary figures of cinema, directed 45 feature films, from The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries to Winter Light and Persona. His movies were spare, austere and invariably morose, dealing with themes running the gamut from loneliness and mortality to sexual desire and religious faith.

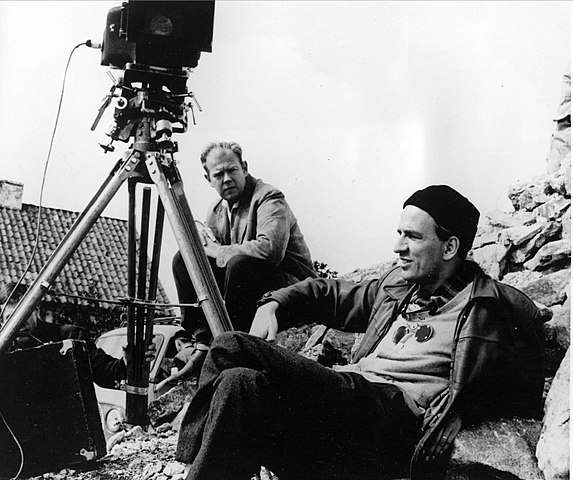

Von Trotta, a German filmmaker, is an admirer. Having watched her first Bergman movie, The Seventh Seal, in 1960, she was hooked. So much so that Searching for Ingmar Bergman starts on the bleak, rock-strewn beach where The Seventh Seal was shot 60 years ago. Images of Max von Sydow, the blond Swedish actor who starred in it, appear and reappear like an apparition from the past.

Bergman died in 2007, which means that Von Trotta must often rely on file footage. A viewer is more enlightened by her conversations with the directors Olivier Assayas and Ruben Östlund, the critic Stig Björkman, and the actresses Liv Ullmann and Gunnel Lindbloom.

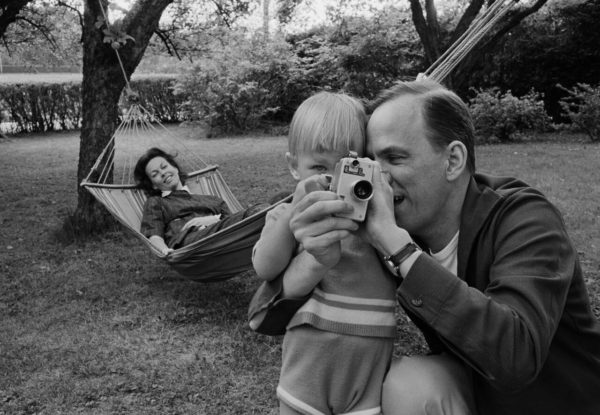

Ullmann, one of the celluloid beauties of the 20th century, knows Bergman better than most of her contemporaries, having been one of the six women who gave birth to his nine children. One of his offsprings, Daniel, a film director himself, says Bergman was closer to his own childhood than to his daughters and sons, a critique that strongly suggests he was a distant or absent father.

Von Trotta’s documentary is linear, somewhat choppy, and leaves out a lot. Despite its flaws, it manages to draw in a viewer.

Von Trotta has precious little to say about his youth, apart from the fact that he was raised in central Stockholm, where his father was the pastor of a church, and that he looked up to Adolf Hitler as a father figure after having visited Nazi Germany in 1936.

Judging by the comments of the interviewees, Bergman treated his actors with consideration and reserved his temperamental outbursts for his crew. He had a remarkable knack for choosing strong, sensitive and intelligent actresses, and demanded their full understanding of a script. During rehearsals, which always took place in cool and dimly-lit places, he insisted on maintaining full control.

Though outwardly self-confident, he had doubts about his craftsmanship and kept his ego in check. Bergman appeared to have no regard for industry awards, dismissing them as “these irrelevant things.”

One of the most dramatic episodes in his career occurred in 1976, when he was accused of tax evasion by the Swedish government. Bergman, shocked and flabbergasted, felt betrayed by the ruling Social Democratic Party, which he had supported, and contemplated suicide. He left Sweden and decamped in Los Angeles, but was unhappy there. Eventually, he settled in Munich, where he also directed plays.

Meticulous to the end, Bergman planned his own funeral and stored his casket in a barn.

Bergman was a complex man, but Von Trotta skips over the telling nuances that define him as person and film director.