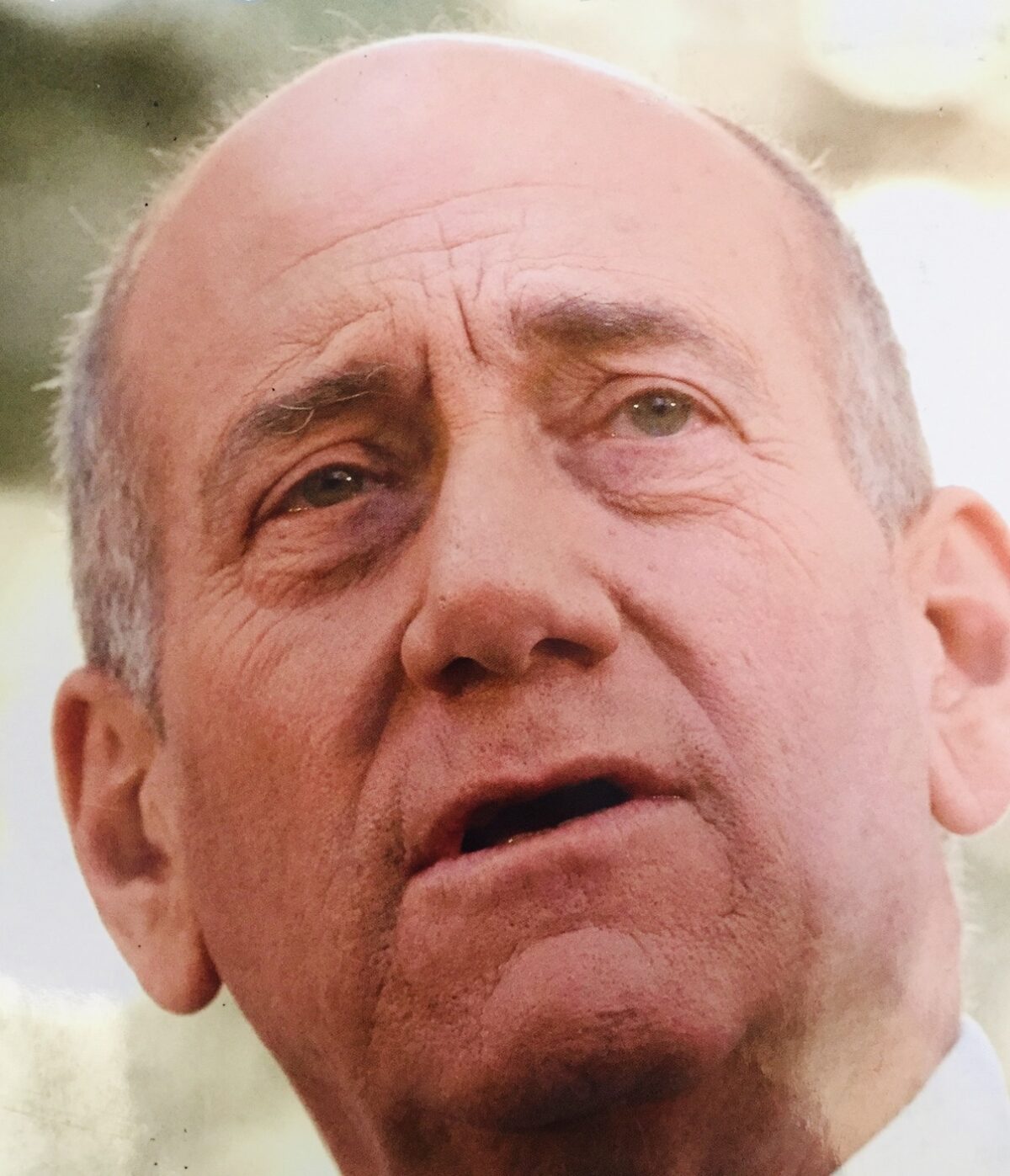

Ehud Olmert was Israel’s prime minister for a relatively short time during a consequential era in its turbulent history.

A hawk who reinvented himself into a dove on key security issues, he was in office from 2006 to 2009. His predecessor was Ariel Sharon. His successor was Benjamin Netanyahu.

During these eventful years, Israel fought a month-long cross-border war with Hezbollah in Lebanon, led a serious effort to reach a peace agreement with the Palestinian Authority, bombed Syria’s nuclear reactor, engaged Syria in fruitless peace talks, and launched the first war against Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

Olmert might well have been prime minister for considerably longer had he not been caught up in a scandal that ruined his political career. Convicted of bribery and money laundering in the Holyland Hotel Affair, he spent 16 months in prison from the winter of 2016 onward.

It was there, in the Maasiyahu penitentiary in central Israel, that he wrote much of his book, Searching for Peace, which was originally released in Hebrew and which was published recently by the Brookings Institution Press.

As one might imagine, Olmert believes he was a victim rather than a felon. “I have never been a criminal,” he writes in chapter one. “To the contrary, every office I held was seen by everyone who dealt with it as a model not only of efficiency and effective decision making, but also of probity.”

Claiming he successfully cleared his name in all but “a small number of tangential and minor charges,” Olmert contends his convictions were based on “highly questionable evidence” stemming from his tenure as mayor of Jerusalem and minister of industry and trade.

He argues that a “tremendous array” of right-wing forces in Israel and the United States coalesced to smear his reputation. Vehemently opposed to territorial compromise in the West Bank, they were intent on “erasing me from the political map.”

This was an ironic turn of events, given Olmert’s ideological orientation.

Raised in a home in awe of Vladimir Jabotinsky, the founder of the Revisionist school of Zionism, Olmert was a Herut Party loyalist completely in sync with the ideas of Menachem Begin of the Likud Party.

An ardent advocate of the settlement movement in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, Olmert was a fierce opponent of the peace treaty with Egypt, which required a full Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula.

Born in Tel Aviv in 1945, he was the son of Mordechai and Bella Olmert, East European Jews from Harbin, China, who arrived in British Mandate Palestine in 1933. They lived in the rudimentary village of Shuni, which had no running water or electricity.

Olmert’s father, a hardline Zionist, was the head of Herut’s settlement division. In this capacity, he built new settlements and reconstructed Mishmar Hayarden, a village in the Galilee which was destroyed by the Syrian army during the 1948 War of Independence.

Following in his footsteps, Olmert joined a right-wing student body in his freshman university year. He then worked as an aide to parliamentarian Shmuel Tamir. He was elected to the Knesset in 1973, several months after a ceasefire ended the Yom Kippur War. In 1988, he was appointed treasurer of the Likud.

Olmert regrets having voted against Israel’s 1979 peace treaty with Egypt. In retrospect, he believes, it was “the proper and unavoidable thing to do.” He credits Moshe Dayan, the then foreign minister, with having laid the groundwork for Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s historic visit to Israel in 1977 and Egypt’s decision to trade land for peace.

Begin could not accept the idea that the “inevitable next step” after Israel’s withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula would be its relinquishment of the West Bank. As Olmert writes, “His failure to understand this sowed the seeds of unending conflict. Our spiritual servitude to the idea of the Greater Land of Israel proved catastrophic.”

In theory, Olmert subscribes to this notion with all his heart. “But if we are ever to end the state of perpetual war (with the Arabs), we still have to give up the territories we captured from Jordan in 1967. Most of them. Almost all of them.”

Begin’s unwillingness to vacate the West Bank, he notes, strengthened the settlement movement, which, he warns, endangers “the future of Israel as a Jewish state.” And Begin’s support for Palestinian autonomy rather than statehood in the West Bank was a non-starter. “Begin was not ready for compromise,” he says.

Turning to Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, Olmert claims the Israeli army was not prepared for the kind of warfare it encountered and therefore suffered heavy losses.

He describes his tenure as minister of health as “one of the most gratifying periods” of his career. Addicted to his job, he claims he reformed the health care system.

Olmert credits Yitzhak Shamir, the then prime minister, with having exercised admirable restraint during the first Gulf War in 1991. At the request of U.S. President George W. Bush, he scrapped a plan to send commandos to western Iraq to destroy missile batteries that had launched missiles at Israel.

“Sometimes, strength is knowing when to say no. Shamir had that in spades.” He clearly admires Shamir who, he says, was “forged of steel. I never met anyone with (his) determination and mental strength.”

In 1993, shortly after the start of the Oslo peace process, Olmert was elected mayor of Jerusalem. “I was steeped in the popular rhetoric about the holy city … I thought that one could never speak of dividing (it) … By the time I left the job a decade later, I knew there was no way to avoid changes to (its) municipal borders …”

“The necessity of dividing the city is grounded in the simple fact that wide parts of its current territory are not, and never were, part of the Jerusalem we dreamed about,” he goes on to say. “These areas are filled with hundreds of thousands of Palestinians … We are locked into slogans about a unified Jerusalem. But in reality, the city is not unified. How many Jewish Jerusalemites ever set foot in Sur Bahar or Shuafat, the Palestinian neighborhoods of Jerusalem? Day-to-day Jerusalem is a divided city. The contact between the two populations is minimal.”

The suicide bombings that convulsed Jerusalem during the second Palestinian uprising affected him deeply. “I attended every funeral of every terror victim in the city,” he says. “These were the worst days of my life.”

He blames Yasser Arafat, the then chairman of the Palestinian Authority, for having turned a blind eye to the attacks.

Olmert entered national politics after the newly-elected prime minister, Ariel Sharon, asked him to join his administration in a senior role and intimated he would succeed him. Olmert was appointed minister of industry and trade and deputy prime minister. In 2005, he became finance minister.

During this period, Sharon and his colleagues broke away from the Likud to form the centrist Kadima Party. With Sharon incapacitated by stroke, Olmert replaced him as prime minister.

One of the problems that concerned him was Lebanon, where Hezbollah reigned supreme. “No subject troubled me more, or took up more of my time,” he writes. Olmert feared that the Shi’a Lebanese militia might try to replicate Hamas’ success in kidnapping Israeli soldiers. In June 2006, Hamas operatives from the Gaza Strip emerged from a tunnel and killed two Israeli troops and kidnapped another soldier named Gilad Shalit, who would be held in captivity in Gaza for the next six years.

A month later, Hezbollah ambushed an Israeli patrol near the Lebanese border, killing several soldiers. Israel’s chief of staff, General Dan Halutz, was ready to respond and “send Lebanon back to the Stone Age.” Olmert had no desire to launch a war, as he told U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, but he was certain that Hezbollah’s naked aggression required “a massive response.”

Olmert approved the bombing of its rocket launchers, command centers and television station, but he would not allow the destruction of Lebanon’s civilian infrastructure. He denies he overreacted to Hezbollah’s bloody provocation.

Realizing that a “total victory” was unattainable, Olmert hoped to achieve a kind of victory that would deter Hezbollah in the future. He believes he attained this objective. “For fifteen years, Hezbollah has avoided conflict with Israel … This is a direct result of (its) crushing defeat (it) suffered in the Second Lebanon War.”

One may question his conclusion, given the cross-border skirmishes that have since occurred. But on the whole, Hezbollah has been deterred from pushing Israel into a third Lebanese war.

Unlike Netanyahu, Olmert supported the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement. Although it was far from optimal, it was preferable to an Israeli air attack on Iranian nuclear sites, which, he contends, would have failed to eliminate the threat. In his view, Netanyahu used Iran politically to whip up fear among Israelis and to make his voters dependent on his leadership.

Criticizing Donald Trump for having withdrawn from the agreement, he says, “Trump brought nothing positive to the table, and instead undid all the good the Iran deal had brought.”

Through the mediation efforts of the then Turkish prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Olmert attempted to make peace with Israel’s bitter enemy, Syria. Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian president, agreed to indirect talks. Several rounds of negotiations took place, but the process collapsed when Syria insisted on an Israeli announcement agreeing to return the Golan Heights before all the other issues had been settled.

As the negotiations wore on, Israel was busy with preparations to destroy Syria’s nuclear reactor in Deir al-Zour, which was only months away from being activated. “Successfully destroying the reactor in September 2007 was, without question, the most important achievement of my career,” he says.

He had been concerned that Syria might retaliate, setting off a war. But in the end, the Syrians took it in the chin quietly.

In reaction to Hamas rocket bombardments, Olmert initiated the first Gaza war on December 27, 2008. He sought “a more significant ground operation,” but was stymied by his defence minister, Ehud Barak. “The opportunity to land a final, irrevocable blow on Hamas was missed,” he says. “I was actively undermined by my defence minister … Politics got in the way.”

As might be expected, Olmert devotes a substantial portion of his book to the ubiquitous Palestinian issue.

He describes Israeli settlements in the West Bank as “a political statement” designed to thwart Palestinian statehood. He then delves into his “diplomatic vision.” His plan was to initiate negotiations with the Palestinian Authority with the aim of reaching a full and final peace accord. “If we succeeded, great. If not, we would unilaterally withdraw from the great majority of the West Bank, including parts of municipal Jerusalem. We would establish a permanent border for our country.”

With this in mind, Olmert tried to “create an atmosphere of cooperation, mutual respect, trust and patience. I was determined to focus on the future, not the past.”

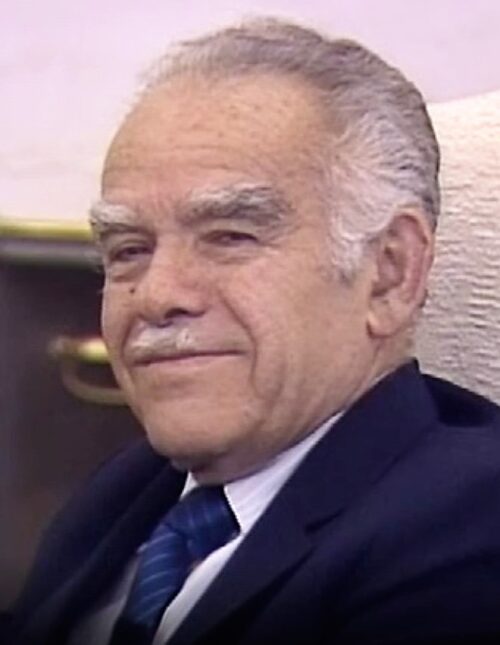

Arafat had given up on reaching a negotiated settlement with Israel, he claims. Mahmoud Abbas, his successor, seemed eager to turn a new page in the Palestinians’ often bumpy relationship with Israel.

During his first meeting with Abbas, Olmert told him “everything in on the table, including Jerusalem. There is no subject I refuse to discuss.”

“I had no interest in another round of posturing,” he adds in an implicit reference to previous talks. “I wanted to negotiate for real.”

Much to Abbas’ surprise, Olmert accepted the principle of Israel’s return to the 1967 borders. “I had no intention of allowing widespread building on other other side of the pre-1967 border known as the Green Line, but I felt it necessary to let off some steam from time to time, allowing a limited degree of construction, mainly within the settlement blocs, that would anyway remain under Israeli control and really did not undermine any future deal.”

Compared to previous Israeli proposals, Olmert’s plan was audacious, granting Palestinians statehood in 94 percent of the West Bank.

He explained his proposal to Rice on May 3, 2008. “I talked about the 1967 borders with land swaps,” writes Olmert. “I said we would annex about six percent (of the West Bank) and give (the Palestinians) the same amount of land within Israel. I said we would be able to take in a few thousand Palestinian refugees … on an individual, humanitarian basis, not an any ‘right of return.'”

As for Jerusalem, Israel would withdraw from Arab neighborhoods and keep Jewish ones, including those built after the Six Day War. Five states — Israel, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and the United States — would exercise sovereignty in the Holy Basin, or Old City.

Olmert presented his unprecedented proposal, his final offer, to Abbas shortly afterward. “It wasn’t put in writing. We did, however, draw up a map that included the most critical places to annex, as well as land we would be willing to exchange for it.”

“I believed this was a winning formula,” he says. To which Abbas responded, “This is serious.”

The long and short of it is that Abbas never formally replied. “Thirteen years have passed, and Abbas still hasn’t gotten back to us,” he says. “I was within a hair’s breadth of fulfilling the dreams of millions of Israelis who longed for peace. I had seen the Promised Land, but was not allowed to enter.”

Perhaps Abbas considered Olmert a lame duck prime minister. At this point, Olmert was mired in criminal investigations regarding crimes that were both “trivial and false.” In September of that year, he resigned.

Olmert is convinced that Abbas would have signed an agreement had Netanyahu been truly interested in peace. “He was much more of a talker than a doer,” he says of Netanyahu. “He followed a single principle. Survival. Israel’s survival in its present format, but mostly, his own political survival.”

To this day, he remains convinced that Israel must resolve the Palestinian question. “The occupation is an open wound, both for them and for us. It demands a solution that will require significant, painful and unprecedented concessions, first from our side, but also from theirs. I have no problem saying we have to go first, because if we don’t, no solution will ever come.”