The biggest misconception of the present-day Middle East is a distinction between “good guy” liberal democrats and “bad guy” Islamists. There is no such distinction because there are no such democrats, at least in the tumultuous fertile crescent of Syria and Iraq.

What we’re seeing in these two countries is a death struggle between Islamists, mainly along the lines of a 1,300-year-old theological dispute that produced Shiism and Sunniism, the rival Islamic groups well represented in both states.

Western onlookers would do well to keep this reality in mind as their governments try to cobble together a consistent position toward these conflicts. The United States has been scrambling since 2011 to find “moderates” among the anti-Assad opposition, whose foe America opposes on account of his support for Hezbollah and connections with the Iranian mullahocracy.

Meanwhile, the Obama administration has long promoted the view that things are going just fine in Iraq, largely to support its withdrawal of troops in December 2011.

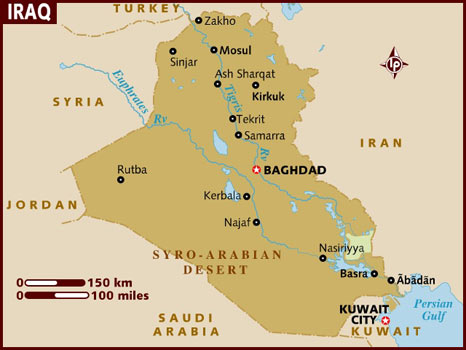

Things are not, so to speak, going just fine. An Islamist proto-regime called the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria has taken Mosul, Tikrit, and Fallujah, and is on the march to Baghdad. The irony is that while the United States rhetorically supports the anti-Assad forces in Syria, it is now chastising their very equivalents in Iraq who are attacking a government largely obedient to Iran, the very regime in whose opposition the Americans have taken the anti-Assad side in Syria.

American policy in these countries is, in other words, an inconsistent mess, especially when one considers that it is both sides that are Islamist, and that these two states are one large battle ground in the territorial confrontation between the two principal Islamic sects.

Movements in favour of liberal democracy, which the Americans are eager to arm and fund, are not to be found among the major players in this conflict.

But this misunderstanding also pervades the public.

This morning, I happened to look at the Wikipedia entry discussing the relations of Assad and Iran during the Syrian civil war. The article’s introduction notes how crucial Iranian armaments and money have been to the Ba’athist effort, but doesn’t mention that religious agreement is the principal point of connection between them. Instead, it says that Iran sees Syria as a crucial part of its interest. No kidding, one thinks: Iran has an interest in Syria because of its sizable Shiite population.

Ditto for Iraq’s Shiite-dominated government, which Iran has pledged to help defend against what it calls an “extremist” faction. Real reason: ISIS is a Sunni revanchist group which Iran does not want to see succeed in Iraq, whose population is majority Shiite and which includes several important cities to their religion.

There is little to choose between these two warring sects for an American power still clinging to the hope that the Muslim world — of which Iraq and Syria are keystone states — can be reformed into peaceful and secular democracies. It’s very well for the United States to have power to project in the Middle East, but this power is useless when it has no clear interpretation of the conflict, let alone a strategy to advance its interest.

If I were the U.S. State Department, I would try to tilt American favour toward the Sunni side, on the one hand, because there are more of them than the Shiites, and on the other, because they can probably do less tangible damage to Israel than the Shiites, who have the major Persian state that is rhetorically committed to wiping Israel from the map and who generally seem better organized.

Overall, however, the United States should be trying to promote, to the greatest extent possible without needless employment of force, a balance of power between the two groups so as to make possible a long-term stability.

The only hope for such a future is in giving up on the existing borders of Iraq and Syria, at least in a de facto sense.

These boundaries are the relics of French and British mandatory regimes, emanating from the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire following World War I. They were not designed with confessional demographics in mind, as is painfully clear with this decade’s stunning display of sectarian war.

A partition of the countries is inevitable for the future, which, if the United States cannot help to facilitate, should at least abstain from delaying.

Jackson Doughart is founding editor of the new commentary website The Hustings (www.hustings.ca).

-30-

| Click to reply all |