Plessy v. Ferguson, a U.S. Supreme Court verdict of immense magnitude, drew little national attention when it was handed down in 1896, but its effects on race relations in the United States were staggering and long-lasting.

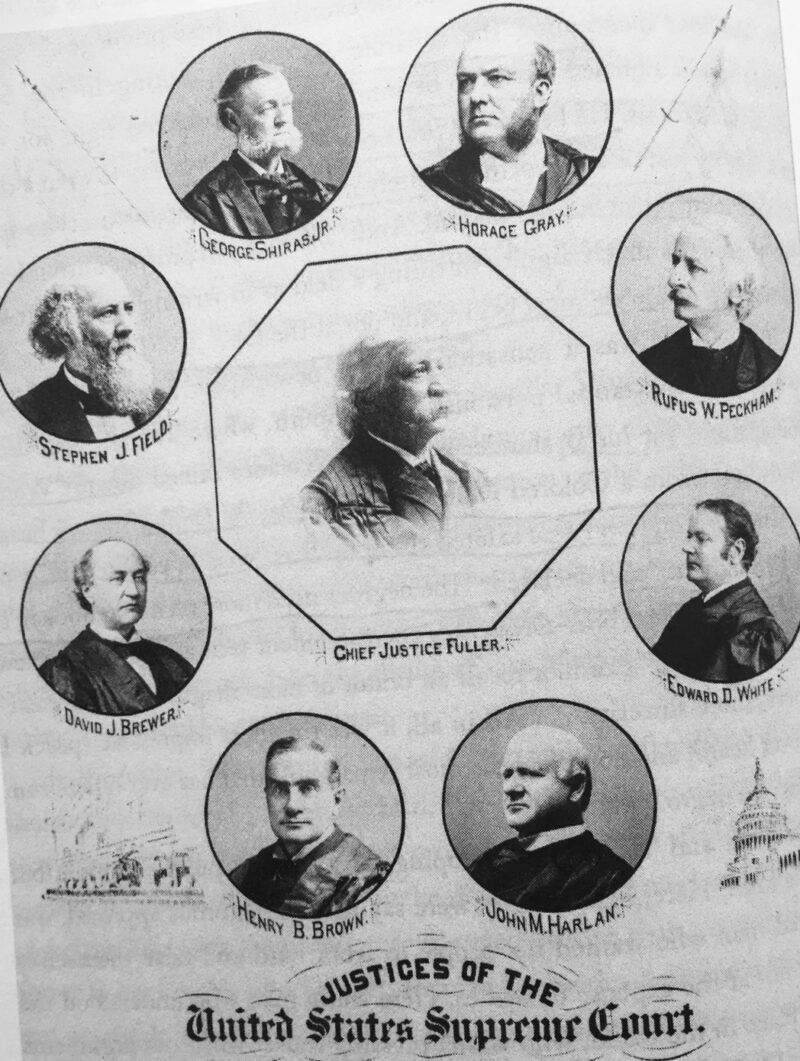

The ruling, written by Henry Billings Brown, upheld the Separate Car Act, which Louisiana had enacted in 1890 “to promote the comfort of passengers” on railways under separate but equal conditions. In fact, the legislation, expressly designed to ensure that white and black Americans could not be seated in the same railroad car, enshrined Jim Crow segregation practices in the Southern states.

Writing for the majority of justices, Brown, a Northerner, ruled that the Separate Car Act was not a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibited states from interfering with the rights of U.S. citizens. In reality, Plessy v. Ferguson had a devastating impact on the civil rights of African Americans for decades to come. Indeed, the period that followed was the darkest in modern African American history.

“It gave legal cover to an increasingly pernicious series of discriminatory laws in the first half of the twentieth century,” writes Steve Luxenberg in his gripping and thoroughly researched book, Separate: The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson (W.W. Norton & Company).

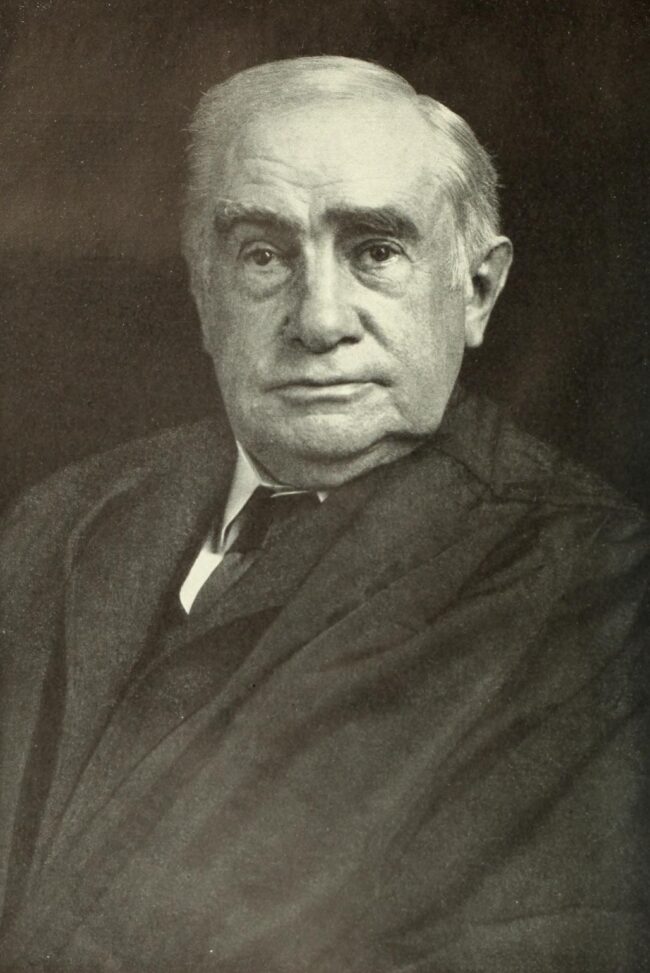

The key figures in this historic clash were Louis Martinet, the mixed-race publisher of a New Orleans newspaper who sought to test the constitutionality of the Separate Car Act; Albion Tourgee, a white journalist, author, lawyer and advocate for racial equality who presented that argument to the U.S. Supreme Court; Homer Plessy, a light-complexioned shoemaker from New Orleans’ Creole community who bought a first-class ticket from the East Louisiana Railroad in 1892 to challenge the separate but equal doctrine; John Ferguson, a Louisiana judge who deemed the Separate Car Act as a legitimate exercise in legislative authority and was thus the defendant in the case, and John Harlan, a Southerner from a Kentucky slave-holding family and the lone U.S. Supreme Court dissenter in this monumental case.

Luxenberg, an editor at The Washington Post, draws on archival collections, letters and diaries to recreate an era whose reverberations are felt to this day, particularly in the wake of the police murder of African American George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25, an event that led to nation-wide protests calling for racial justice.

As Luxenberg points out, the web of Jim Crow edicts and regulations with which the South was so inextricably identified originated in the North, which abolished slavery during the U.S. Civil War.

The notion of separate seating for different classes of people was introduced in the third decade of the 19th century.

In 1838, the railway era in America was ushered in with the maiden trip of an Eastern Rail Road train departing from Salem, Massachusetts. Tickets were sold to all travellers without regard to race, but whites and coloreds went to separate cars.

“At first, the practice provoked no outcry, not even from the abolitionist movement,” says Luxenberg. But within a few years, civil rights activists demanded a law forbidding it. White passengers insisted that their “comfort and convenience” would be seriously diminished if they were forced to share “the company of blacks.”

They lost their appeal, and by mid-century Jim Crow seating in railroads was a thing of the past in many northern U.S. states.

But in New Orleans, a city of European and African culture where men and women of color were well established, segregation was standard procedure. The City Railroad Company hewed to the separation convention, which conductors rigorously enforced.

The native-born mixed race Creoles, whose complexions ranged from nearly black to almost white, felt closer to whites than blacks and resented being shunted to separate cars.

Creoles thought they had achieved equal rights with the passage of the 1875 Civil Rights Act, a landmark achievement of the Reconstruction period following the Civil War. It read, “All persons shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges,” regardless of race.

Much to their dismay, the Civil Rights Act was widely ignored and rarely enforced, thereby enabling railway companies to direct passengers to separate seating. As Luxenberg says, colored passengers had “to cope with a maddening, shifting kaleidoscope of practices that differed from Southern state to Southern state, from railroad to railroad.”

He adds, “As long as the Civil Rights Act cases remained in limbo, equality would have to stand in line behind whim, confusion and the predisposition toward prejudice.”

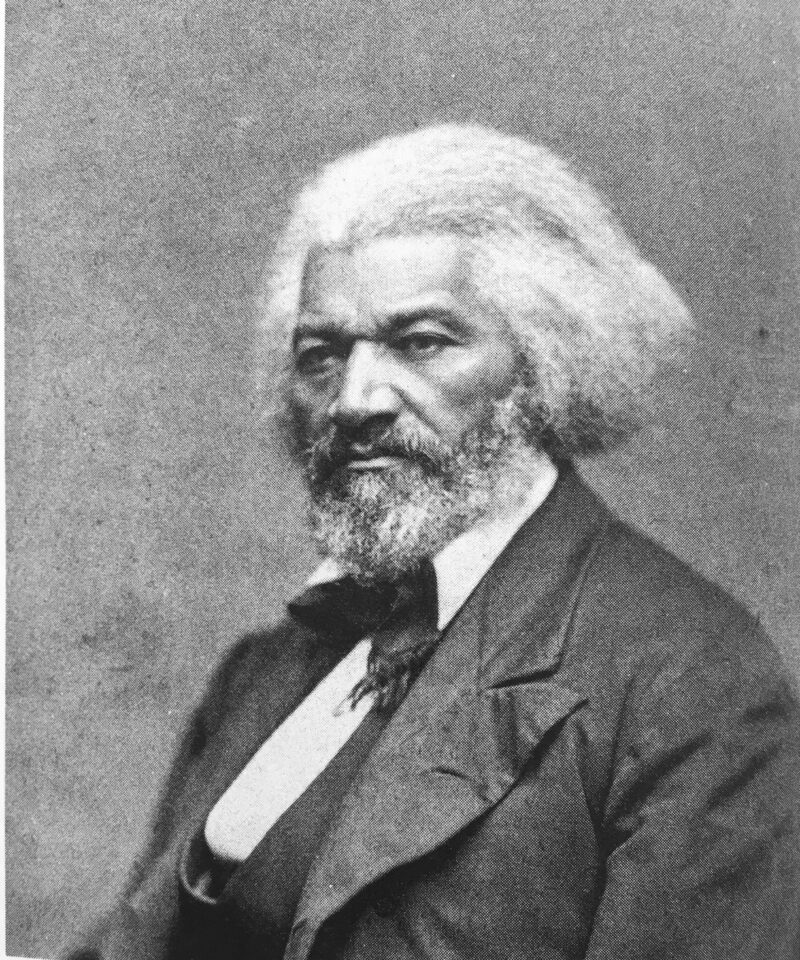

As the gains of Reconstruction fell by the wayside in Washington’s bid to rebuild the United States as a unified nation, African Americans suffered the consequences. Frederick Douglass, a major figure in the black community, observed that while slavery had been eliminated by President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, bigotry “hampers every step of our progress” toward genuine equality.

People of color could neither be silent nor settle into a “servile and cowardly submission” to injustice, he said.

In 1888, Mississippi passed a law requiring “all railroads carrying passengers” to provide “equal but separate accommodation for the white and colored races.” It was the first time the separate but equal concept had been enshrined in law rather than in custom.

Two years later, Louisiana followed suit with the Separate Car Act. The Times-Democrat, a newspaper published in the state, claimed it was not designed to humiliate “negroes,” but to “prevent any such dangerous doctrine as social equality, even in its mildest form.”

Shortly after its passage, Albion Tourgee denounced the new edict in a newspaper column. His blast prompted Martinet to form the Citizens’ Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law.

Tourgee, having concluded that unjust laws could best be overturned by courts rather than by legislatures, decided to challenge the edict by sending Plessy — a mild-mannered 29-year old Creole who was one-eighth African and seven-eights Caucasian — to purchase a ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad’s train from New Orleans to the resort town of Covington. Martinet agreed with Tourgee’s strategy.

As per Tourgee’s plan, Plessy did not obey the conductor’s order to leave the white car and was detained. Ferguson, in his ruling, declared that “separate” cars were legal, though he could not be certain whether white and black cars were really “equal.”

On the heels of his ruling, the Louisiana Supreme Court unanimously approved separation on trains within the state, claiming that the Separate Car Act treated the races with “perfect fairness and equality.” The court rejected Tourgee’s argument that it was discriminatory toward people of color.

Tourgee’s next step was an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, but it was a risky tactic. As Luxenberg puts it, “Defeat could mean an endorsement of separation that would be difficult to undo.”

In his presentation, Tourgee argued that the Separate Car Act violated every post-Civil War federal law guaranteeing African Americans the same rights as whites. White newspapers in New Orleans gave the proceedings a minimum of coverage.

Seven of the eight justices on the U.S. Supreme Court (one judge was not in attendance due to family issues) upheld the Separate Car Act. As Brown wrote in his judgment, “A statute which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races.”

Proceeding from the assumption that separate did not necessarily mean unequal, and that separate seating reduced the potential of friction between whites and blacks, Brown noted, “Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation.”

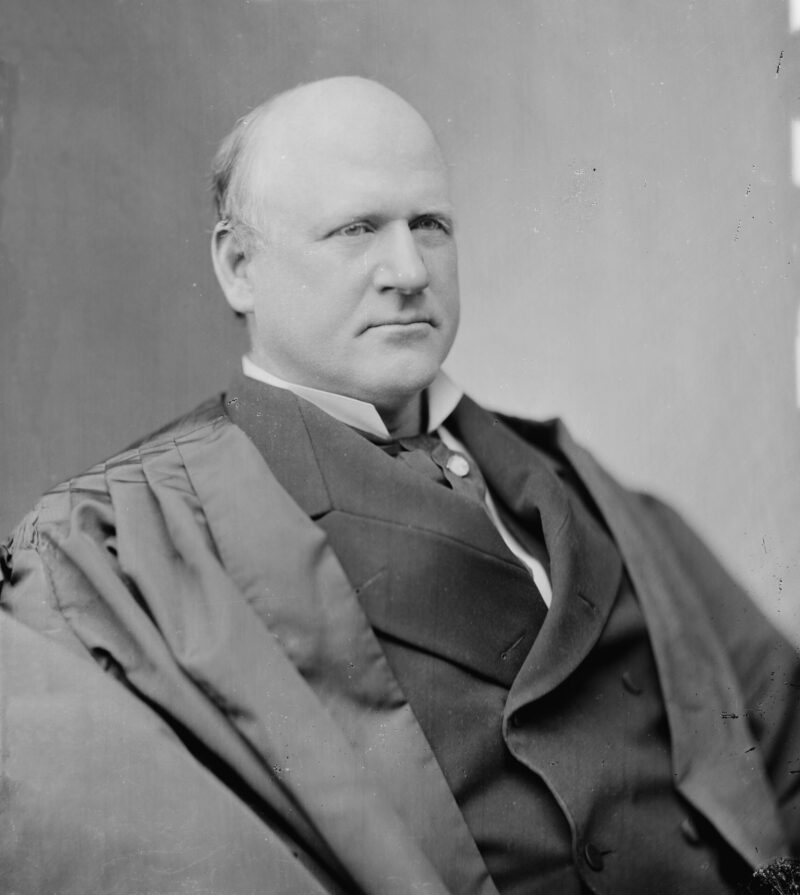

Casting a jaundiced eye on Brown’s judgment, Harlan presciently predicted that it would, in time, “prove to be quite … “shameful.” The Separate Car Act, he reasoned, “cannot be justified upon any legal grounds” and was contrary to the “color-blind” constitution, which “neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”

With his courageous dissent, Harlan had come a long way in his approach to race relations. Three decades earlier, Harlan, who regarded slavery with deep ambivalence, had opposed its abolition, as well as the first civil rights. In his opinion, they imposed “radical” changes in the “fundamental law of the land.”

But now, after a series of violent Ku Klux Klan attacks on African Americans in his own state, which had been a member of the Union during the Civil War, Harlan confided to a friend that federal intervention was the only method to “root out the evil” of institutional racism and segregation.

Clearly, Harlan was a man ahead of his times. But as Luxenberg points out, his spirit of tolerance did not extend to Chinese immigrants. Harlan, along with most of his fellow justices, classified the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act as constitutional.

“He had his blind spots, his prejudices, his preconceptions,” Luxenberg observes. “But unlike others, he had confronted his past, examined his fears, and had emerged with the belief that, for the white and black races, equality and opportunity could not survive if they came in different colors.”

Almost 60 years would elapse before the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Plessy v. Ferguson. In the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, the justices decreed that separation was inherently unequal.

It was a great victory, but more difficult battles lay ahead in the campaign for racial justice in America.