In his prime, from the late 1960s to the opening years of the 21st century, Seymour (Sy) Hersh was one of the great investigative reporters of our times.

A dogged journalist with a nose for news, he uncovered the 1968 My Lai massacre in Vietnam, which earned him the 1970 Pulitzer Prize for international reporting, and exposed the 2004 Abu Ghraib prison scandal in Iraq, which added yet more lustre to an already distinguished career.

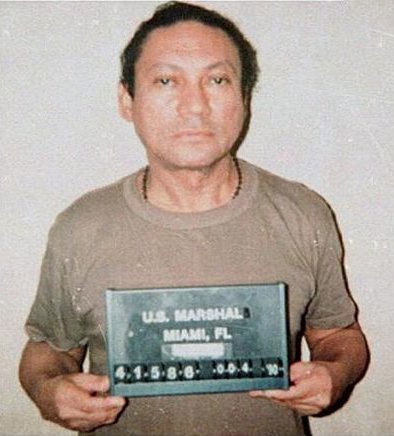

An old-school reporter who values scrupulous research and objectivity, Hersh is also credited with having unmasked the United States’ illegal bombing campaign in Cambodia, the American role in the overthrow of Chilean President Salvador Allende and the drug dealing of corrupt Panamanian President Manuel Noriega.

In addition, Hersh has written a slew of books from the The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House to Chain of Command: From 9/11 to Abu Ghraib.

It goes without saying that few journalists have compiled such a stellar record of achievement.

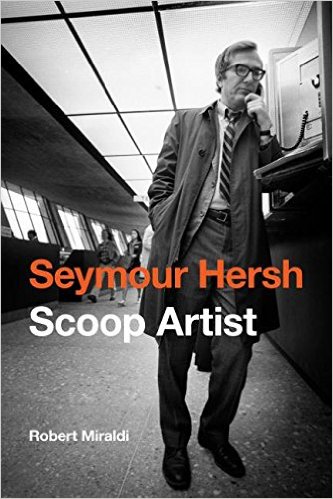

Robert Miraldi, in Seymour Hersh: Scoop Artist (University of Nebraska Press), paints a nuanced portrait of a man he describes in the prologue as “crusty, crabby and aloof.” Miraldi, a journalist who teaches at State University of New York, did not gain access to his subject, forcing him to rely on Hersh’s enormous body work, his comments on it, his speeches and his interviews with the media. Despite this handicap, Miraldi’s book is both thorough and illuminating.

Interestingly enough, Hersh — the son of Isador Hershowitz, a Lithuanian Jewish dry cleaner who arrived in America in 1921 — had no formal training in journalism when the City News Bureau, a collective owned by Chicago’s five daily newspapers, hired him in 1959.

Before landing an entry-level position at the City News Bureau, where reporters chased down murders, rapes and muggings, Hersh studied history and then law at the University of Chicago. After flunking out of law school, he held a succession of dead-end jobs.

City News Bureau, a boot camp in journalism, was straight out of The Front Page, the 1928 Broadway play that was made into a Hollywood film.

An editor who worked closely with Hersh says he was “very aggressive.” Having learned the fundamentals of reporting, he and a partner started to publish a weekly newspaper in a Chicago suburb. The gig lasted about a year.

Subsequently joining the UPI news agency, Hersh was sent to South Dakota as its lone correspondent. He viewed the posting as a stepping stone to a better job. In 1964, he joined the Associated Press as a general assignment reporter in Chicago. “The challenge in this, of course, was mastering new issues every day and having to produce stories at lightning speed, “writes Miraldi. “There was a deadline every minute.”

Thanks to his productivity and resourcefulness, Hersh was moved to the Pentagon, where he acquitted himself well. But when his hard-hitting seven-part series on the Pentagon’s chemical and biological warfare program was emasculated into one bland article, his days at AP were numbered. Demoted back to general assignment, Hersh quit. “The AP was good to me,” he would say. “It was my apprenticeship.”

Working as a freelancer, he wrote his first book on America’s weapons of mass destruction. He then spent a year as press secretary for presidential aspirant Eugene McCarthy.

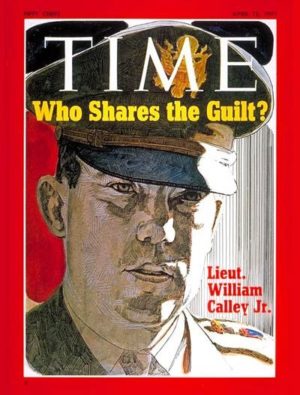

Back in journalism again, Hersh received the tip of a lifetime when he was told that an American army officer, William Calley, had been charged with spearheading an atrocity in a Vietnamese village. Certain that this could be a first-class story, Hersh homed in on it. “I started making calls and got nowhere,” he recalled. “Most reporters would have given up.” Hersh’s perseverance paid off. Eventually, he tracked down Calley, who spilled the beans.

Life, the nation’s largest mass circulation magazine, declined the story, as did its competitor, Look. Resorting to Plan B, Hersh sold it to David Obst, a 23-year-old anti-war activist who had recently started the Dispatch News Service to disseminate stories about the Vietnam war that no one else would produce. Thirty five American dailies bought it, including the Boston Globe and the Miami Herald. Overseas, major British newspapers carried it as well.

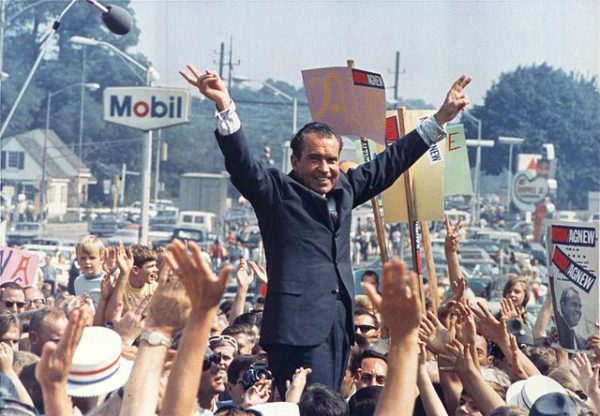

The Nixon administration was enraged by Hersh’s expose. “It’s those dirty rotten Jews from New York who are behind it,” President Richard Nixon railed.

Miraldi says Hersh was influenced by the Vietnam reportage of David Halberstam, a New York Times correspondence, and I.F. Stone, whose newsletter on current affairs was a must-read in Washington, D.C. “Stone’s maxim that ‘all government’s lie’ was adopted by a legion of young reporters, including Hersh.”

Hersh, whose ambition was to work for the New York Times, was offered a job there in 1972 by the managing editor, A.M. Rosenthal, with whom he would have a mercurial relationship. His first assignment took him to Paris, where the Vietnam peace talks were unravelling.

Hersh was also placed on the evolving Watergate story, which would bring down Nixon’s presidency, and was assigned to cover the Central Intelligence Agency. Hersh’s discovery that President Manuel Noriega was a glorified drug dealer resulted in the U.S. invasion of Panama and Noriega’s arrest and imprisonment.

For all his acumen, Hersh missed one of the most important stories of the day. Informed by a fellow reporter that U.S. Vice President Spiro Agnew had accepted bribes, Hersh, astonishingly enough, dismissed it as a non-story. Miraldi treats his faux pas lightly: “A few misses did not affect Hersh. He was non-stop in pursuit of scoops.”

Miraldi devotes several pages to one of Hersh’s most controversial books, The Samson Option: Israel’s Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy. Believing that Israel should be held to the same standard of accountability as other countries, Hersh claimed that Israeli duplicity and American connivance had allowed the Jewish state to develop an atomic capability.

After leaving the New York Times, he began writing for the New Yorker magazine. Tipped off about abuses at a prison near Baghdad, Hersh wrote three articles about the wrongdoing. The stories rocked the Bush administration and thrust Hersh into the limelight yet again.

Hersh’s newest book, The Killing of Osama Bin Laden (Verso), essentially deals with two separate topics — the U.S. commando raid that culminated with Bin Laden’s assassination in 2011 and the decision by U.S. President Barack Obama in August 2013 to call off an expected aerial bombing campaign in Syria.

Claiming that Obama “told the world a series of lies” about the killing of Bin Laden, Hersh maintains that Pakistan was directly complicit in his death. Indeed, a senior Pakistani general insisted he would have to be killed. The United States continues to maintain that the mission was an all-American affair.

With respect to Syria, Hersh discloses that Obama cancelled a planned attack against Syria after British intelligence confirmed a Russian claim that the Syrian army had not deployed chemical weapons in attacking rebels near Damascus. An analysis demonstrated that the sarin gas supposedly used by Syria did not match samples known to exist in Syria’s arsenal.

Hersh writes that the Al Nusra Front, an affiliate of Al Qaeda, had been developing chemical weapons. But he doesn’t come out and say that the Al Nusra Front carried out the attack for which the Syrian government of President Bashar al-Assad was blamed.

The Americans had been contemplating a “monster” air strike to eradicate Syria’s military capabilities. But after receiving word from Britain that Syria had not been involved in the sarin attack, the chairman of the U.S. joint chiefs of staff, General Martin Dempsey, convinced Obama that a strike would be an unjustified act of aggression.

Delving into the Syrian morass still further, Hersh says that weapons and ammunition funnelled from Libya to Syria via Turkey ended up in the hands of Syrian jihadists opposed to Assad’s regime.

He discloses that Israel, Russia and Germany passed on information about the whereabouts and intentions of radical jihadist groups to the Syrian army. In exchange, Syria provided information about its own capabilities and intentions.

Assad, via a contact in Russia, offered to reopen peace talks with Israel. The Israeli government rejected the offer, being convinced that Assad was effectively finished.

Hersh writes about these events in a sober, matter-of-fact style, staying clear of even traces of sensationalism.