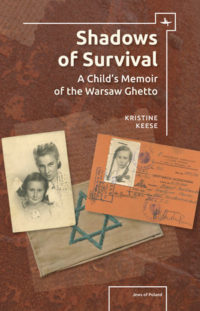

With the 75th anniversary of the April 19 Warsaw ghetto uprising looming, Kristine Keese’s Shadows of Survival: A Child’s Memoir of the Warsaw Ghetto (Academic Studies Press), is certainly timely.

Keese, born into an assimilated Jewish family in the Polish capital, was eight years old when she and her mother were forced into the ghetto. They managed to escape, passing as Christians with false documents. In this spare and affecting work, she tells a story of survival against the greatest of odds.

Shortly after Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, German aircraft bombed the apartment building in which they lived. “Our house was one of the first to be destroyed in the heavy bombing,” she writes. For the next little while, they moved around before finding accommodation in the so-called small ghetto.

Hunger dogged its inhabitants. One day, she and her mother, Genia, were walking back home from a bakery with a loaf of bread when small boy darted at them and bit into it. “He did not try to grab it, just bite into it.”

This was the “new normal.”

For a brief time, they were allowed to receive food packages from Brazil containing such exotic luxuries as coffee, tea, canned fruit and canned fish. Genia sold them to restaurants outside the ghetto.

During the first year of their incarceration, Genia considered baptizing Kristine, believing that her chances of survival would improve. In the meantime, she encouraged her to memorize Christian prayers and rituals, a practice that would prove to be very helpful.

Food shortages grew increasingly acute, engendering a sense of doom. “I saw groups of people huddled around garbage cans … looking for food … We were told to keep away from them as they might carry infectious diseases, just the way Aryans were told to keep away from Jews, who, they were told, carried typhus.”

Rumors began circulating that Jews were being murdered on a massive scale. In July 1942, the Germans started deporting Jews from the ghetto. Keese and her mother managed to avoid the roundups. Jasio, her uncle, provided them with scraps of food. “I remember the bread as very dark and heavy. Often there were strange objects inside, stones or jagged pieces of metal, so one had to be very careful eating it.”

They lived under a black pall. “The knowledge that deportations meant death must have been universal. I knew it, but it had no name. If you had asked me what I thought happened to my friends, Ella her sister and Marek, when they were taken, I had an image of them falling into a big black hole, never to be seen again.”

By then, realizing what lay in store if they remained in the ghetto, many of her mother’s friends had escaped into there Christian side. “They had friends they could rely on. This was especially true for members of certain professions. Doctors, lawyers, actors and musicians could rely on their prewar Aryan colleagues to prepare hiding places for them. No small matter, as the penalty for hiding a Jew was death.”

Her aunt Cesia survived by living with a Polish friend in the countryside as her housekeeper. Cesia’s husband and son, who never joined her, were killed.

Keese and her mother did not leave the ghetto primarily due to lack of funds. “She had jewelry that she saved, but no cash to buy her way out, to pay someone to keep us, which was the most common way to hide.”

Finally, Genia managed to escape by joining the Polish resistance movement. She placed her daughter in a boarding school.

During the 1944 uprising in Warsaw, she and Genia lived in an apartment building that took a direct hit from a German bombardment. “We rushed back to the shelter. Running with us was a small dog that was on fire. It was a very frightening sight and most people seemed worried that he would set other things ablaze. I ran through the nearest open door and grabbed a blanket, which I threw over the dog. Its owner appeared and took over.”

Keese and Genia were placed on a farm, and shortly afterwards, she was enrolled in a convent school. No one knew she was Jewish, and she successfully passed as a Catholic.

She describes the end of the war as the lifting of a death sentence. But old habits died hard. “The habitual behavior of caution, not telling the truth, distrust of strangers and preserving a cover had become who I was. I did not know how to act otherwise. I certainly did not want to be exposed as a Jew among my schoolmates or the nuns.”

Traumatized by her experiences, Keese did not utter the word “Jew.” For many years after 1945, she admits, she would not acknowledge she was Jewish.

Much to her sorrow, she discovered that her father, Bolek, had been killed during the war.

Her mother, she says, regarded the future of Poland with optimism despite news of pogroms. As for herself, Keese was certain that “one should not advertise one’s Jewish past.”

Not surprisingly, she and her mother left Poland, immigrating to the United States. Keese earned a BA in philosophy from Cornell University and an EdD from Harvard. Most recently, she was a social science researcher at Brandeis University’s department of sociology. Until her death in 2016, she worked on her husband’s fishing boat, which was a long, long way from Warsaw.