The status of Soviet Jews deteriorated sharply after World War II as the Cold War intensified and Jewish citizens in the now-defunct Soviet Union developed a more acute national identity, says a European scholar.

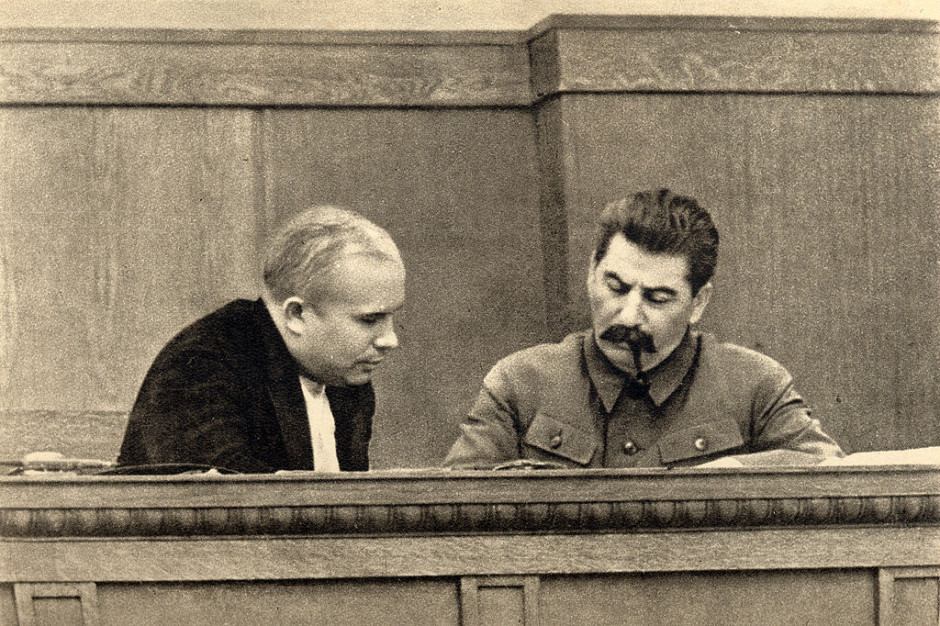

Alongside this development, the relationship between Jews and non-Jews in the Soviet state, headed by Joseph Stalin, was damaged by a resurgence of antisemitism, said Diana Dumitru, a history professor at the Ion Creanga State Pedagogical University in Chisinau, Moldova.

Currently a visiting professor at the University of Toronto, she has studied these interlocking issues and discussed them in a lecture at the University of Toronto’s Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies on April 4.

For Soviet Jews, the postwar period was punctuated by disillusionment and disappointment, said Dumitru, the author of a newly-published book, The State, Antisemitism and Collaboration in the Holocaust (Cambridge University Press).

The scarcity of housing in the Soviet Union in the wake of the war spawned mutual animosity, she said, focusing on the situation in the Ukraine. Ukrainian Jews who had been evacuated from their homes during Germany’s blitzkrieg discovered they had been expropriated and occupied by their gentile neighbors, who declined to return them. Heated arguments broke out, giving rise to antisemitic slurs.

According to Dumitru, wartime anti-Jewish propaganda disseminated by the Nazis left its mark on the local population. “Antisemitism had grown to a level Jews had never seen before,” she said in a reference to the era from the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution onward.

After the war, Soviet officials acknowledged that Germany had stirred up latent antisemitic feelings, but claimed that its gravity had been exaggerated by Jews.

Further tension surfaced when Jews learned that some of their non-Jewish neighbors had betrayed other Jews during the German occupation.

With the Holocaust still a fresh memory, increasing numbers of Jews embraced their Jewish identity, grew more vocal in protecting their national rights and fought antisemitism.

The refusal of the Soviet government to permit the publication of a “black book” on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union was rooted in the belief that Jewish suffering should not be singled out, she added.

Jewish loyalty to the motherland was questioned by Soviet officialdom, which looked askance at the voluminous flow of letters between Jews and their relatives in the West. And the warm welcome that Israeli ambassador Golda Meir was given in 1948 by about about 50,000 Jews during her visit to the Choral Synagogue in Moscow also turned heads in the Kremlin.

Israel’s tilt to the West, following the Soviet Union’s recognition of the Jewish state, aroused suspicion as well in Moscow, Dumitru pointed out.

The marginalization of Soviet Jews proceeded as the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was disbanded, the “rootless cosmopolitan” campaign got under way and the so-called Doctors’ plot emerged.

Stalin’s campaign against “cosmopolitans” — a code word for Jews — led some Soviet citizens to conclude that open antisemitism was acceptable, said Dumitru, whose talk focused on the years from 1945 to 1953.

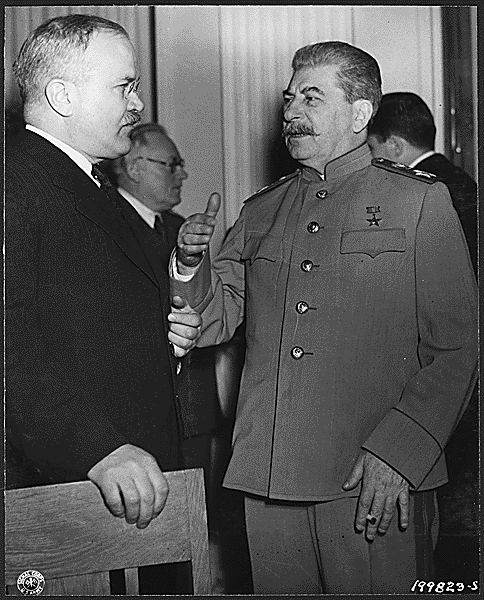

Stalin’s sudden death saved Soviet Jews from possible deportations and pogroms. In his last year, he was supposedly mentally unstable, and even his closest associates, including Vyacheslav Molotov, the longtime foreign minister, feared for their lives.

“Stalin just went nuts,” she said.