For more than 500 years, between the 10th and 15th centuries, Spanish Christians, Jews and Muslims coexisted in what Jeffrey Gorsky calls “unparalleled harmony.” This period, known by some as the convivencia, a word which means living together in Spanish, ended tragically in persecution, forced conversion and expulsion.

Gorsky’s masterful account of this golden era unfolds in Exiles in Sepharad: The Jewish Millennium in Spain, published by The Jewish Publication Society. It’s a nuanced work that acknowledges both the heights and depths of the Jewish experience in Spain, where Jews enjoyed a level of prosperity, acclaim and power not matched anywhere else in Europe.

Jews in Muslim and Christian Spain lived within an unsettled framework of symbiosis and conflict, says Gorsky, an American lawyer and diplomat. In the Muslim kingdoms, Jews prospered until an intolerant brand of North African Islam forced them to flee to Christian Spain, where they were welcomed in exchange for financial and other services.

“But even at the best of times, Jews never were fully safe and secure under the convivencia,” Gorsky notes.

Antisemitic riots broke out in the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon in 1391, compelling Jews to choose between death and conversion. One-third to one-half opted for the latter, in the greatest mass conversion in modern Jewish history.

Jewish converts, or conversos, became enormously successful in Spanish society, marrying into the Catholic aristocracy and attaining high positions in government and the church. Their success fostered resentment among “old” Christians, who accused them of secretly practising Judaism. The Inquisition initially targeted conversos, but Jews were ultimately affected. The rationale for their expulsion, resulting in the dispersal of Sephardi Jews around the world, was that their very presence undermined the Christian faith of the conversos.

Jews arrived in the Iberian peninsula after the destruction of the first temple in Jerusalem, but their well-being was jeopardized by the Visigoths. A Germanic tribe that controlled much of Spain by the end of the fifth century, they promulgated the most repressive anti-Jewish laws until that juncture.

Muslim invaders in the eighth century displaced the Visigoths, establishing a culturally-rich caliphate that lasted about 700 years. Jews, regarded by Muslim rulers as valuable and trustworthy allies, generally flourished in Muslim Spain, or al-Andalus.

“The most successful Jews became courtiers, fully assimilated (except for religion) in the life of the Islamic court,” writes Gorsky, citing Samuel ben Joseph Halevi ibn Nagrela, the grand vizier of Granada, as a prime example.

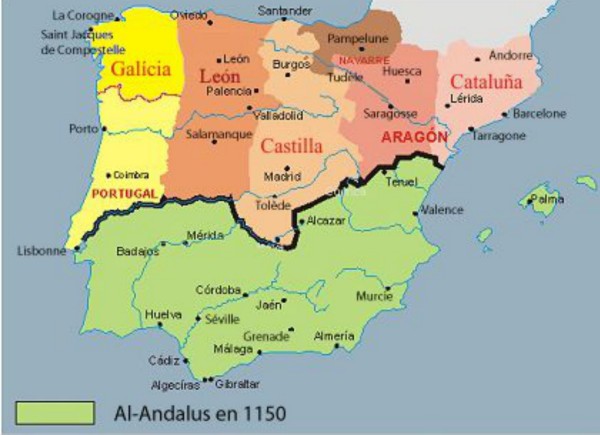

The rise of Islamic fundamentalism in al-Andalus prompted the majority of Jews to flee to the Christian kingdoms of Castile, Leon, Navarre and Aragon. By the 12th century, most Spanish Jews lived almost exclusively under Christian rule, largely in Castile and Aragon. By then, 80,000 Jews resided in Christian Iberia, in a population of about two million Christians and one million Muslims.

Christian Spain was a land of religious tolerance and fanaticism. At a time when Britain and France were expelling their Jewish residents, the Christian kingdoms offered Jews “the most tolerant refuge in Europe,” Gorsky observes. With Christian kings busy reconquering territory from Muslims in the reconquista, Jews were perceived as valuable subjects. But traditional anti-Jewish attitudes and tropes remained deeply embeded, causing periodic violence.

In Christian Spain, Jews were prominent in science, medicine, astronomy, astrology, alchemy and cartography. One of the greatest, most enduring figures was the philosopher Moses Maimonides. Jews were also employed in tax farming, which contributed to their unpopularity.

Antisemitic resolutions passed by four ecumenical Lateran Councils between 1123 and 1215 marginalized European Jews as well, Gorsky says. These measures isolated and denigrated Jews, altered their status from a legal and theological point of view and set the stage for the riots of 1391. These pogroms spelled the demise of convivencia, which, in the final analysis, had been a marriage of convenience for both sides.

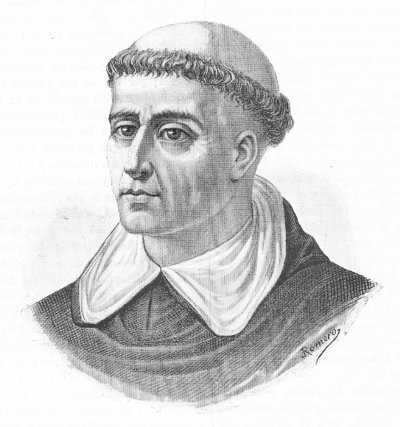

The riots, though fueled by political and church leaders, were mainly instigated by one person, Ferrand Martinez, an archdeacon who had launched an anti-Jewish campaign 12 years earlier. Outbreaks of violence erupted in, among other cities, Toledo, Seville, Cordoba and Segovia. In the face of these outbursts, many Jews converted to Christianity. One of the most important converts, Solomon ha-Levi, who had been the chief rabbi of Burgos, changed his name to Pablo de Santa Maria.

The rapid creation of a new class of Christians, or conversos, was unprecedented. As Gorsky puts it, “Never before in Europe had so many Jews been assimilated into a Christian nation.” As “new” Christians, conversos enjoyed untrammelled upward mobility, establishing alliances with the most powerful families in Spain and filling key positions in the church hierarchy. The mother of Juan de Torquemada, an uncle of the future inquisitor general of the Inquisition, was probably a converso himself, Gorsky speculates.

Nonetheless, conversos were viewed in some circles as insincere converts — Jews at heart and thus heretics and enemies of Christianity. Gorsky argues that conversos aroused the ire of “old” Christians because they maintained close family and social ties to Jews and clung to Jewish rituals and traditions.

Assessing their level of sincerity, Gorsky believes that, by the mid-15th century, some conversos were devout Christians, while still others were secret Jews. In the final analysis, many, if not most conversos, were practicing Christians, he adds.

Whatever the case, conversos were impacted by the passage of the first comprehensive racial exclusion laws in modern Europe, passed in 1449 and not abolished until the 19th century. If a converso was unable to prove Christian lineage for four generations, he was barred from public office and prevented from holding an important position in the hierarchy of the church.

The last vestiges of convivencia were demolished by Ferdinand — supposedly a descendant of a converso — and Isabella, the royals who had previously allied themselves with Jews and conversos and had begun their reign embracing religious tolerance.

Their drastic decision to expel Jews from Spain was made on the assumption that the Jewish community had undermined the Catholic zeal of the conversos. As Gorsky points out, the 1492 Edict of Expulsion brought Spain’s policy toward Jews into conformity with much of the rest of Europe. The bulk of Sephardi Jews settled in North Africa, the Middle East and the Balkans.

Jews who chose conversion were not required to leave and could keep their property. The most prominent Jew to convert was Abraham Senor, a court Jew who took the new name of Fernan Nunez Coronel.

By 1500, Gorsky estimates, 250,000 Spaniards in a population of seven to nine million were classified as conversos. The most zealous of conversos became founding members of the Jesuit order and, ironically, leading members of the Spanish Catholic church.

Who could have known.