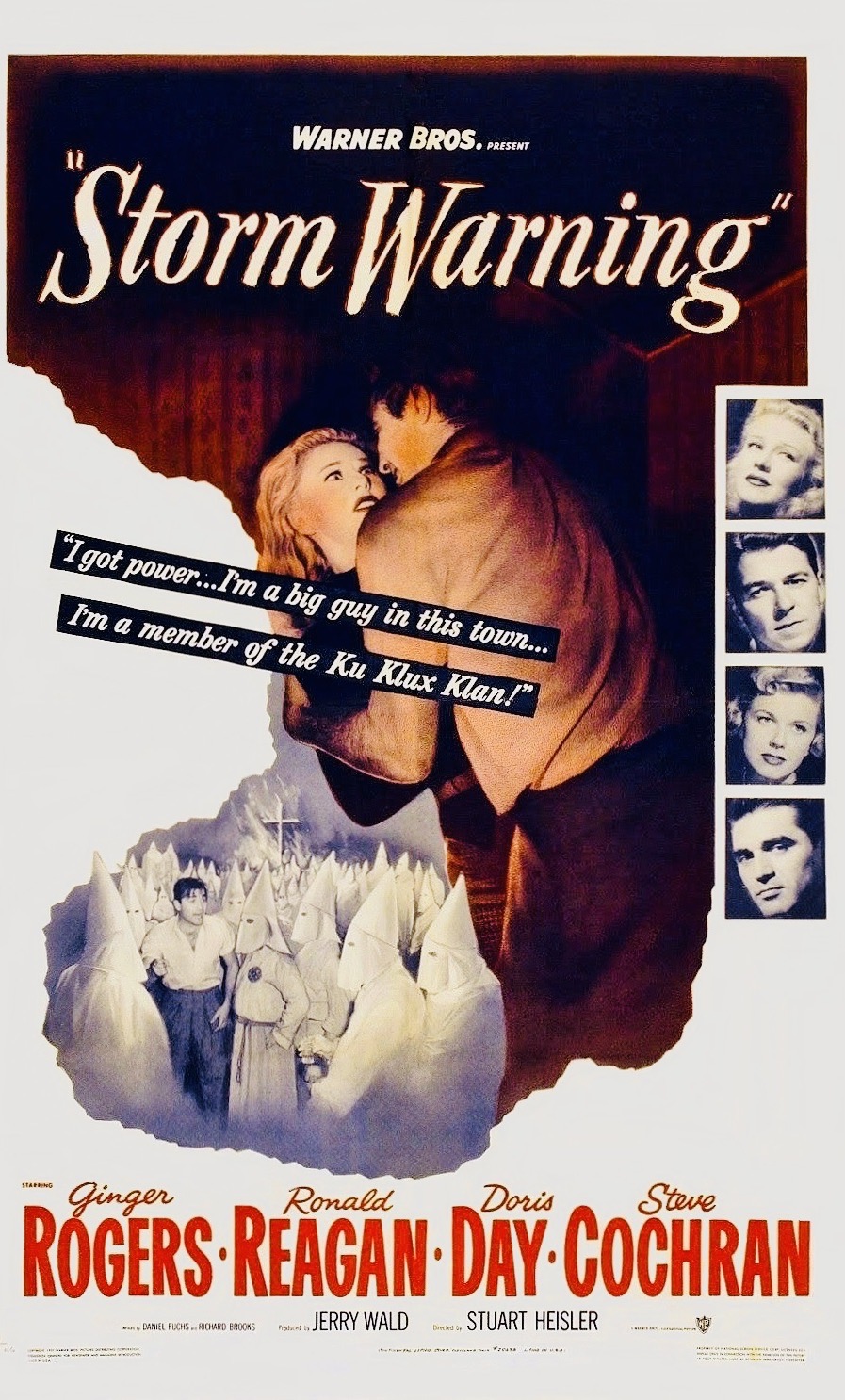

Stuart Heisler’s taut drama, Storm Warning, is a rarity, one of the relatively few mainstream Hollywood films that have been critical of the Ku Klux Klan, a notorious racist organization that gained immense popularity, even respectability, in the United States in the first decades of the 20th century.

Recently screened on the Turner Classic Movies channel, it was preceded by the release of Black Legion and followed by, among other films, Mississippi Burning and A Time To Kill.

Released by the Warner Bros. studio in 1951, and starring Ginger Rogers, Doris Day and Ronald Reagan, this one hour and 33- minute picture comes out unequivocally against Klan hatred and violence, but avoids condemning its unadulterated racism. Its reticence is not hard to understand. Institutionalized segregation was the norm in the 1950s, when the United States was still very much riven by racial separation practices.

Given these parameters, Storm Warning treads carefully so as not to offend racially prejudiced viewers, particularly in the South.

Shot in film noir style, with a menacing score designed to underscore a sense of uncertainty and dread, it is set in Rock Point, a drab mythical town in flyover America. It is dismissed as a “dead end” place by a man on a bus sitting next to Marsha Mitchell (Rogers), his travelling companion and a dress model from New York City. On a whim, Marsha stops here to visit her newly-married sister, Lucy Rice (Day).

Unable to find a taxi, she walks to a recreation center where Lucy works. En route to her destination a few blocks away, she witnesses a murder and catches sight of one of the killers. A bunch of men clad in white Ku Klux Klan robes and hoods have fatally shot a middle-aged white man and left him sprawled on the sidewalk. The victim is a newspaper reporter who denounced the Klan in his articles. When she meets her sister, Marsha tells her what happened.

The scene shifts to the office of country prosecutor Burt Rainey (Reagan), who was born and raised in Rock Point. Rainey wants to solve this crime, unlike two local policemen who have reported it to him. Clearly, the Klan is woven into the fabric of the town, with people either reluctant or afraid to talk. Rainey’s associate, though, denounces Klan members as mere “hoodlums dressed up in sheets.”

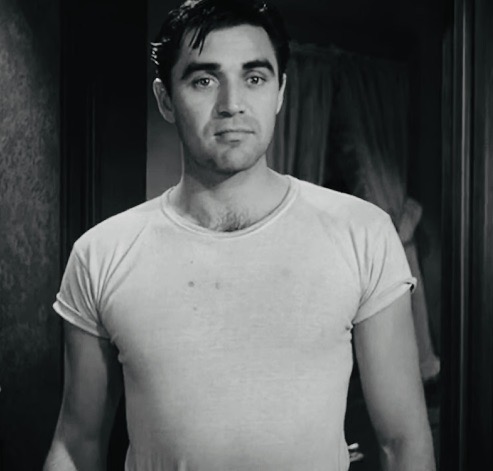

Much to Marsha’s surprise and distress, she recognizes Lucy’s husband, Hank (Steve Cochrane), a truck driver, as one of the Klan murderers. When Marsha informs Hank that she “saw the whole thing,” Hank desperately tries to change the conversation. “Outsiders hiding in Klan robes” killed the reporter, he says before changing his story.

Unimpressed by his far-fetched claim, Marsha blurts out the plain, unadorned truth about Hank’s criminal complicity. Cornered by Marsha’s forthrightness, Hank confesses, but lamely adds that the deceased reporter was “looking for trouble,” and that the Klan merely sought to “scare” him.

Rainey, meanwhile, is warned to back off, else he will ruin the town’s reputation. Attempting to protect her sister, Marsha disappoints Rainey by saying she would not recognize any of the Klansmen. Hank, nevertheless, is worried that she may spill the beans and incriminate him. Barr (Hugh Sanders), Hank’s venal employer and the local Klan leader, voices concern about Marsha’s reliability as well.

As these developments unfold, Rainey prepares an indictment against the Klan, having learned that Barr has committed fraud and is guilty of income tax evasion. Confronting Marsha, Barr tries to intimidate her, urging her to lie at the forthcoming coroner’s inquest. For good measure, he insists that the Klan is actually a positive force.

With tensions rising, Rainey’s associates implore him to drop the case against the Klan, claiming it will be bad for business, tarnish the town’s image, and ruin his career. Refusing to bend to their demand, he presses Marsha to tell the truth at the inquest. Mindful of Lucy’s vulnerability, she refuses, prompting Rainey to lament that the Klan is immune to law and order. Later, Barr confirms his fears. As he boasts, “We’re the judges and juries around here.”

This mortality tale does not end there.

Due to two major incidents, Marsha finally summons up the fortitude and courage to expose the Klan, emboldening Rainey to denounce its acolytes as “mean, frightened little men” who desecrate the cross.

Storm Warning, a serviceable and earnest film, batters the ramparts of the Klan with gusto. Rogers, Fred Astaire’s dance partner in a succession of 1930s musicals, acquits herself well in an entirely new role, as does Day, America’s sweetheart. Reagan, a future American president, comes across as Mr. Right, a straight arrow who seeks justice and can do no wrong.