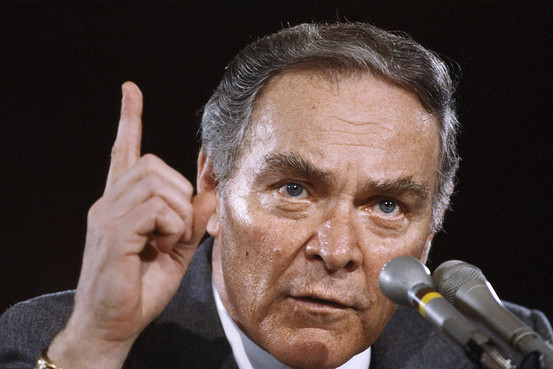

Testifying before a U.S. Senate committee in March 1981, Alexander Haig, the American secretary of state in President Ronald Reagan’s cabinet, said he would work to achieve “a consensus of strategic concerns” among the warring nations in the Middle East in a bid to check Soviet influence.

Haig, a former army general, said his goal was to persuade Arab and Muslim states, as well as Israel, to join an unofficial alliance to counter designs by the Soviet Union in the region. Israel was willing to cooperate, but the Arabs unanimously rejected Haig’s proposal.

And so it died on the drawing board.

But more than 30 years on, Haig’s practical and unheralded idea has found a new lease on life in the form of Israel’s unspoken alliance with its former enemy and neighbor, Egypt.

During the recent 50-day war in the Gaza Strip, Israel and Egypt were usually on the same page with respect to Hamas and Islamic Jihad, bound together in an informal and low-profile strategic consensus in opposition to these Islamist Palestinian organizations.

Egypt’s new authoritarian president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, a former general, chief of military intelligence and defence minister, regards Hamas — an offshoot of the reviled and now banned Muslim Brotherhood– as a dangerous and subversive adversary which must be contained.

His predecessor, Mohammed Morsi, had a very different approach. Morsi, the candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood who was ousted in a July 2013 coup after about a year in office, viewed Hamas in a favourable light. Consequently, 20 days into the most recent Gaza war, he praised Hamas and its allies. As he put it, “Our compass is set on supporting Palestine against the usurping occupier, and we are with any resistance against any occupier.”

Egypt, the first Arab country to sign a peace treaty with Israel, initially adopted a hands-off approach to the Gaza war, which broke out on July 8. In sharp contrast to two previous wars in Gaza, in 2009 and 2012, Egypt did not seriously try to impose a truce until Hamas and Islamic Jihad had been battered by Israel.

True, Egypt urged both sides to halt the escalating conflict shortly after it began, but essentially did nothing for the first few days. Furthermore, Egypt kept its Rafah border crossing into Gaza all but sealed, infuriating the Palestinians.

As the battles raged, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Sisi engaged in frequent and lengthy telephone conversations, Israel’s Channel 10 reported. According to the Times of Israel, Netanyahu was very pleased with the relationship he had formed with Sisi.

The Egyptian media is normally quite hostile to Israel, but during the war, a popular TV presenter and staunch opponent of the Muslim Brotherhood, Tawfiq Okasha, slammed Hamas — which is now banned in Egypt — and complimented “brave” Israel. His surprising comments prompted Al Jazeera’s Lebanese anchor, Ghada Owais, to issue a sharp rebuke.

When the Egyptian government finally offered both sides a concrete ceasefire proposal, the reaction was swift. While Israel accepted it with alacrity, Hamas and Islamic Jihad dug in their heels, angered by Egypt’s curt dismissal of their chief demand, the immediate lifting of Israel’s blockade of Gaza.

Much to Hamas’ chagrin, the truce that ultimately brought the war to a close late last month contained no provision for ending Israel’s siege. The matter will soon be addressed at talks in Cairo, but for the time being, the blockade remains firmly in place.

No one is suggesting that Egypt has suddenly become good friends with Israel. Their peace treaty, signed in March 1979, produced what many pundits describe as a “cold peace.” And on the grassroots level, Israel is extremely unpopular with the vast majority of Egyptians. In 2011, an Egyptian mob ransacked the Israeli embassy in Cairo, forcing some members of the staff to leave the country. Israel is still looking for a permanent location for its embassy.

So while Egypt and Israel quietly worked in tandem during the Gaza war to weaken Hamas and Islamic Jihad, the Egyptian government — which supports a two-state solution to defuse the Arab-Israeli dispute — continued to denounce Israel.

On July 9, just a day after the start of hostilities, foreign ministry spokesman Badr Abdelatty said, “Egyptian diplomatic efforts are aimed at immediately stopping Israeli aggression and ending all mutual violence.”

Two days later, Egypt’s foreign ministry condemned “the irresponsible Israeli escalation in the occupied Palestinian territory, which comes in the form of excessive and unnecessary use of military force leading to the deaths of innocent civilians. This represents a continuation of the oppressive policies of mass punishment.”

Prior to the war, Sisi, who swept to victory in an election this past May, declared he would not invite Israeli leaders to Cairo unless Israel makes real concessions to the Palestinians in peace talks. “Let them just make us happy by giving something (to) the Palestinians,” he said, referring to the formation of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza, with East Jerusalem as its capital.

Sisi’s predecessors, Anwar Sadat, who was assassinated in 1981, and Hosni Mubarak, who was deposed in 2011 during the Arab spring upheavals, often hosted Israeli prime ministers and cabinet ministers in Cairo.

Before last May’s general election in Egypt, Sisi’s campaign manager, Mahmoud Badr, launched a verbal barrage at Israel. “We support anyone who fights the Zionist enemy, but if these weapons are turned toward Egypt, we will chop off the hands that hold them,” he said.

Despite Badr’s venomous attack, Sisi, in a reassuring phone call to Israeli leaders in early June, made it crystal clear that Egypt will continue to honor its peace treaty with Israel.

All the same, Sisi did not invite Netanyahu to his inauguration ceremony. The Israeli daily Yedioth Ahronoth reported that an invitation was not be sent because Israel’s new ambassador to Egypt, Haim Koren, who assumed his post in May, had not yet presented his credentials to Sisi.

Egypt’s snub notwithstanding, the Israelis and Egyptians work closely together to combat Islamic radicalism in the Sinai Peninsula, which Israel returned to Egypt in phased withdrawals after a long occupation following the 1967 Six Day War.

The Egyptian army has destroyed more than 1,300 smuggling tunnels leading from Sinai to Gaza and has escalated its offensive against Al Qaeda-aligned radicals. Israel, turn, has permitted Egypt to station more soldiers and equipment in the Sinai than sanctioned by the peace treaty.

Three months ago, Egypt deployed an infantry battalion in the Taba area, just south of the border, in a bid to prevent more rocket attacks on Eilat, Israel’s most southerly city. In recent years, Eilat, Israel’s gateway to the Red Sea, has been shelled several times.

Sinai, once a tourist paradise, has become the redoubt of an outfit called Ansar Beit al-Maqdis, which shot down an Egyptian helicopter in January, claiming the lives of five soldiers, and subsequently killed several South Korean tourists in Taba heading toward Israel. In 2011 and 2012, Sinai-based terrorists killed a total of more than eight Israeli civilians and soldiers in southern Israel.

So while Israel’s official relationship with Egypt may be tense and sometimes even rocky, the two countries are in accord when it comes to combating Islamic extremism, be it in Sinai or Gaza.