When World War II broke out, Sweden teetered on the fence, declaring neutrality while maintaining trade with both sides in the conflict.

It was not the first time Sweden had chosen to remain neutral. In World War I, Sweden had adopted a similar policy. Now, in 1939, the Swedish government resolved yet again to remain on the sidelines, like Switzerland, Spain, Portugal and Ireland.

In accordance with its position, Sweden signed a trade agreement with Britain while selling iron ore to Germany.

For the duration of World War II, Sweden, fearing invasions from Germany and the Soviet Union, hewed to neutrality. Nonetheless, Sweden assisted Nazi-occupied neighbours and helped European Jews imperilled by Germany. Sweden adhered to this position even as the Swedish media exercised restraint in reporting on Nazi aggression and crimes against humanity in the Holocaust.

It was a masterful balancing act, suggests John Gilmour, a British historian, in Sweden, the Swastika and Stalin: The Swedish Experience in the Second World War (Edinburgh University Press), an important book that sheds light on a relatively little-known aspect of the war.

“Swedish wartime foreign policy decisions were reactive rather than proactive, driven by the demands of the belligerents and the war situation,” he writes.

Sweden’s main political parties, joined together in a social democratic-conservative coalition led by Prime Minister Per Albin, unanimously agreed that neutrality was in Sweden’s national interest.

“Debates over foreign policy arose out of differences over the extent and nature of the changes needed to achieve this aim,” Gilmour observes.

Sweden’s opted for neutrality despite its record of cordial relations with Germany. On the eve of the war, a high-level Swedish military delegation met with Adolf Hitler, Germany’s chancellor, while King Gustav V, the Swedish monarch, conferred a decoration on Hermann Goring, Hitler’s second-in-command, whose first wife had been Swedish. In addition, some Swedish visitors to Germany marvelled at its leadership and institutions.

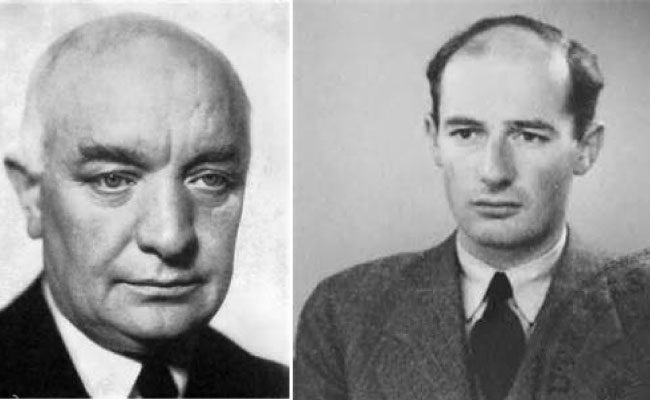

Sweden’s policy was implemented by career diplomat and foreign minister Christian Gunther, who reported to Albin, a social democrat. Although Gunther was generally regarded as pro-German, he adopted a supremely pragmatic approach, reminding foreigners that a strong, independent Sweden was in everyone’s interests. But to British politician Winston Churchill, a future prime minister, Sweden’s neutrality was a self-serving ploy to extract profit from war.

The first test of Sweden’s neutrality occurred when the Soviet Union demanded a naval base in Finland, a redrawing of their border and a mutual defence treaty.

At first, Sweden did not intervene. But after the Soviets attacked Finland on Nov. 30, 1939, in the first shot of the Winter War, Sweden came to Finland’s assistance. The Swedes sent weapons and munitions – rifles, machine guns, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns, howitzers, airplanes, 30,000 shells and 50 million cartridges. And in a humanitarian gesture, Sweden admitted 9,000 Finnish children.

Under German pressure, but in the face of Allied opposition, Sweden shipped iron ore, a strategic commodity, to Germany. Sweden also allowed German troops to cross its territory by rail to Nazzi-occupied Norway. Subsequently, Sweden authorized German aircraft to overfly its territory and reserved three airfields for emergency landings of German planes. Sweden, however, rejected a German demand to seize Soviet warships in Swedish ports.

By 1941, when Sweden’s policy of appeasement toward Germany was at its apogee, 670,000 German soldiers had transited to and from Norway. Clearly appreciative of Sweden’s position, Hitler, in a message to the king, expressed “warm thanks” for Sweden’s cooperative attitude.

Moscow was none too pleased by Sweden’s concessions to Germany. But in general, the Soviet Union regarded Sweden as a buffer zone against Germany.

Due to its concessions to Germany, Sweden was, as Gilmour points out, “on the slippery slope to becoming a German satellite.” Indeed, Goring suggested that Sweden could one day be part of a “greater Germany.”

But as the war ground on and Germany’s losses on the battlefield mounted, Sweden imposed limitations on the transit of German troops and goods through the Swedish corridor.

Throughout this period, the German embassy in Stockholm endeavored to promote Germany’s policies, polish Germany‘s image and influence Swedish public opinion. “German propaganda was prolific [but] it was fundamentally unsuccessful,” Gilmour notes, explaining that Germany’s repressive moves in Norway alienated Swedes.

Although antisemitic currents ran through Swedish society, as elsewhere in western Europe, and immigration was tightened in response to growing xenophobia, the Swedish government was not indifferent to the plight of Jews in Germany.

In the wake of Kristallnacht, in 1938, 3,000 German Jewish refugees were allowed into Sweden. But on the advice of Stockholm’s Jewish community, which feared an antisemitic backlash, the Swedish government pared down the number of Danish Jews who could request protective asylum in Sweden.

Nevertheless, Sweden defied Germany by admitting 7,000 Danish Jews between September and October 1943.

According to Gilmour, Sweden’s generosity was a function of its disgust with Germany’s central role in the Holocaust.

On Dec. 17, 1942, the British foreign minister, Anthony Eden, delivered a speech in parliament in which he spelled out the horrors of the Holocaust in detail. The Swedish media covered the story in full, shocking Swedes.

Sweden also came to the rescue of Jews in Norway, issuing Swedish citizenship papers to Norwegian Jews who had avoided Nazi deportations.

Due to its neutral status, Sweden became a focal point for various attempts to save Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe.

In 1943, Sweden acceded to a plan to admit 20,000 Jewish children on condition that they would be resettled elsewhere after the war.

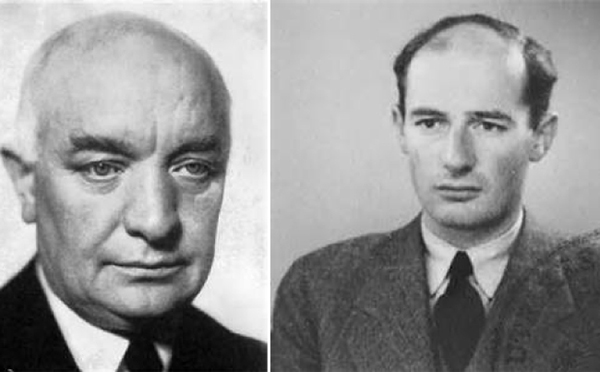

And in the most famous case of Swedish humanitarianism, the envoy Raoul Wallenberg, the first secretary of the Swedish legation in Budapest, issued upwards of 20,000 protective passports to Hungarian Jews in 1944.

Sweden’s policies angered Germany. Fearing German retaliation, Sweden mobilized its armed forces four times throughout these tense years.

In retrospect, Sweden’s neutrality could be regarded in both negative and positive terms. Thanks to Swedish cooperation, Germany was better able to sustain its war effort. Yet a policy of neutrality enabled Sweden to help its beleaguered Scandinavian neighbours and rescue thousands of Jews.