The Kunstmuseum Bern in Switzerland should be congratulated for having established a set of commendable guidelines to deal with the issue of Nazi looted art.

Several days ago, the museum announced that experts had been hired to ascertain whether a fabulous collection of paintings, drawings and lithographs inherited from the son of a German art dealer who had worked with the Nazi regime were in fact “kosher” in terms of provenance. In the interests of openness, the museum also released a catalog of these precious works.

Abiding by its self-imposed standards, the museum made a solemn promise not to accept pieces that had either been stolen from their rightful Jewish owners or forcibly sold under market value.

Christoph Schaublin, the museum’s president, told a press conference in Berlin that it would conduct itself on the basis of the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. The protocol, signed in 1998 by 44 countries, mandates that member governments will scour national collections for looted art and resolve restitution claims.

It’s an admirable policy in light of the fact that scores of museums around the world, including some famous ones, have not behaved as scrupulously and honorably in the past.

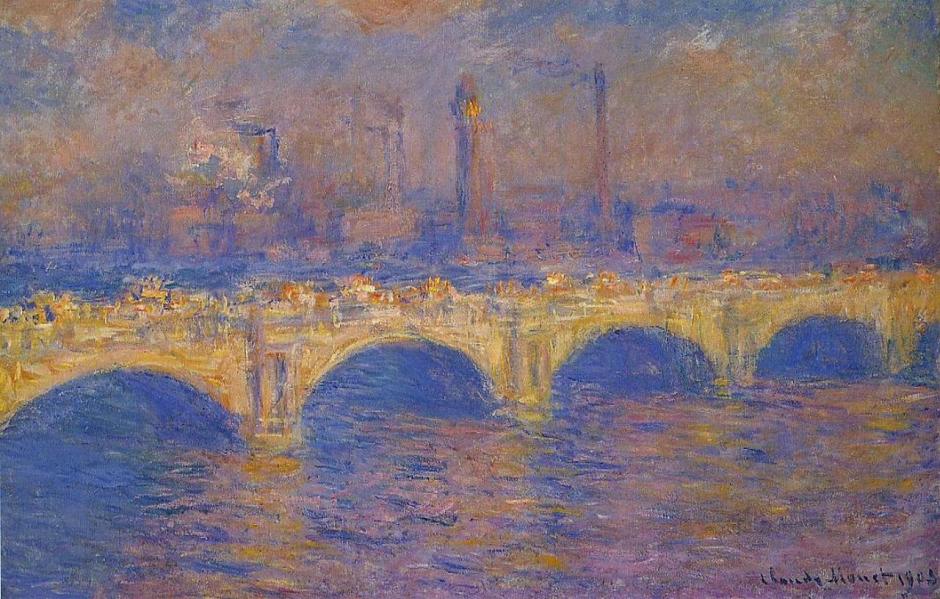

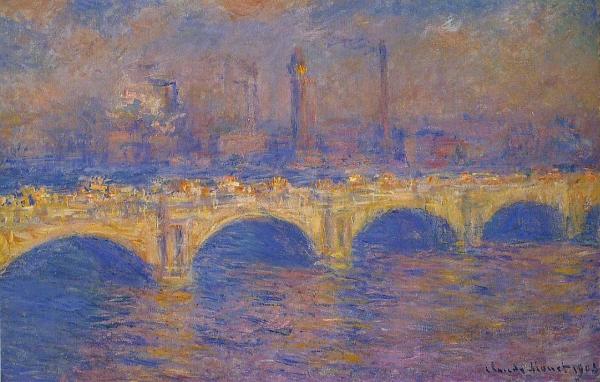

The paintings and drawings in question, reportedly worth hundreds of millions dollars, were bequeathed to the Kunstmuseum Bern by Cornelius Gurlitt, who died last spring the the age of 81. His collection, consisting of upwards of 1,600 works by such masters as Manet, Monet, Cezanne, Pissarro and Gauguin, was amassed by his late father, Hildebrand, a dealer of partial Jewish descent who was one of only four dealers permitted to buy and sell such art.

The Gurlitt trove was discovered by German authorities at Cornelius’ flat in Munich two years ago. Last winter, still more works turned up at his other home in Salzburg, Austria. They include Pissarro’s The Louvre Seen From Pont Neuf, Gauguin’s People Lying Down in Candlelight, Monet’s Waterloo Bridge and Cezanne’s Mont Ste.-Victoire.

By all accounts, more than 100,000 illegally acquired pieces remain unaccounted for today. Even before World War II had ended, the Allies established a special unit to track down this booty. The Monuments, Fine Arts and Archive Section, as it was called, was staffed by 350 investigators from 13 countries. Last February, The Monuments Men, a Hollywood movie inspired by its work and starring George Clooney, Matt Damon and John Goodman, opened in the United States.

The Monuments commission unearthed a considerable number of looted works, but it was not until 1991 that the art trade itself created a database, the Art Loss Register, to facilitate the search for these pieces.

The Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art proved to be a major breakthrough. Its principles, though non-binding, are clear:

Art looted by the Nazi should be identified. Relevant records and archives should be open and accessible to researchers. Resources and personnel should be made available to assist in the identification of such art. Every effort should be made to publicize its identification so that its pre-war owners or their heirs can be located. Efforts should be made to create a central registry of such information. Owners and heirs should be encouraged to come forward and make claims. If such individuals cannot be found, steps should be taken expeditiously to achieve a just and fair solution.

Much to its credit, the German government, a signatory of the Washington Conference, applied these principles to the Gurlitt case. As Germany’s Culture Minister Monika Grutters said recently, “We are facing our historical obligation with the utmost transparency in provenance research.”

If all goes according to plan, the Kunstmuseum Bern will continue to be a shining beacon in determining how museums ought to handle art restitution cases in the future.

This article appeared in the Times of Israel.