Syria has been in agony for the past ten years, its self-inflicted torment expected to fester indefinitely.

A decade ago, on March 15, President Bashar al-Assad’s Baathist regime violently crushed peaceful demonstrations around the country, setting off a civil war in this predominately Sunni Muslim nation.

Syrians in large numbers took to the streets to protest the high cost of living, the soaring unemployment rate, and the glaring absence of democracy.

Assad, a self-declared reformer, assumed he could quell the unrest by brute force. He was dead wrong. As more protesters were killed by security forces, the violence escalated into a full-blown uprising that has yet to subside.

The civil war has exacted an appalling toll on Syria, the beating heart of Arab nationalism.

Upwards of 500,000 Syrians, including 12,000 children, have been killed and more than one million have been wounded. At least 50 percent of its 17 million citizens have been displaced. Five million civilians have been pushed out of Syria, and Syrian refugee camps have sprouted in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq.

Towns and villages have been reduced to rubble. Neighborhoods in major cities like Damascus and Aleppo have been destroyed by indiscriminate bombing raids carried out by Syrian and Russian planes.

Much to international condemnation, Syria has repeatedly deployed banned chemical weapons — the nerve agent sarin and chlorine — to batter its enemies into submission. Syria’s steadfast allies, Russia and China, have blocked the International Criminal Court from investigating its war crimes.

According to United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, Syria is a “living nightmare.” As he put it last week, “It is impossible to fully fathom the extent of the devastation in Syria, but its people have endured some of the greatest crimes the world has witnessed this century. The scale of the atrocities shocks the conscience. Syria has fallen off the front page. And yet, the situation remains a living nightmare.”

Geir Pedersen, the United Nations’ special envoy for Syria, has said that the suffering of the Syrian people defies “comprehension and belief.”

A succession of mediators have tried to defuse the crisis, but to no avail. The civil war rages on, even as these lines are written.

One can safely assume that Assad never expected such a deadly outcome. From the outset, he thought he could ride out the storm unleashed by the Arab Spring, the internal revolts that engulfed Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen from December 2010 onward. These rebellions touched off civil wars and led to the downfall of a procession of Arab leaders.

Assad, having inherited his position after the death of his father, Hafez, in 2000, believed the unrest would not reach Syria, a police state that tolerates no real dissent.

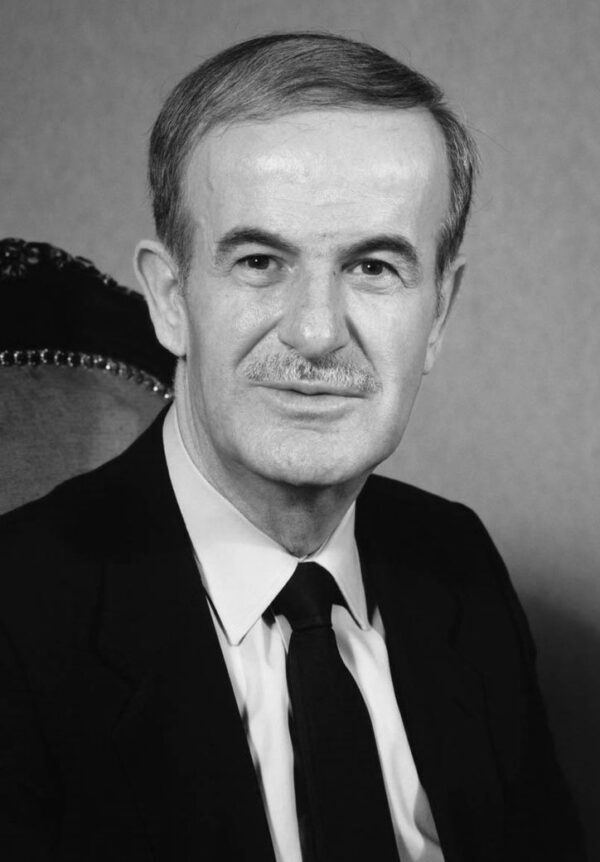

Hafez al-Assad, an air force general and minister of defence who belonged to the minority Alawite sect, which comprises about 12 percent of Syria’s population, seized power in 1970, seven years after a coup d’état staged by the army and the Baath Party. In the winter of 1982, Assad’s regime ruthlessly suppressed an Islamic fundamentalist rebellion in Hama. From that point onward, coup-prone Syria achieved unprecedented political stability.

Bashar al-Assad — an opthamologist by profession — was certain he could maintain the same iron grip on Syria as his father. In retrospect, he was remarkably myopic, having failed to realize that the Arab Spring had emboldened the masses to challenge the stultifying status quo.

On the advice of his advisors, Assad attempted to contain the seething anger by phasing in cosmetic reforms. It was a case of too little, too late. By this juncture, the protesters were demanding his resignation, a red line he refused to cross.

Assad had no intention of stepping down and resigning himself to exile like President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia or to imprisonment like President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt. Certainly, he intended to avoid the horrible fate of Libya’s strongman, Muammar Qaddafi, who was murdered by a mob, his bloodied and mangled corpse displayed for photographers.

Backed to the hilt by the armed forces, the ultimate arbiter in Syrian politics, Assad decided to tough it out, no matter the cost.

Assad’s foes ranged from conventional Syrian nationalists to Muslim radicals affiliated with the Islamic State organization or Al Qaeda. His opponents were aided and abetted by Western powers like the United States, Arab states such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, and Turkey, the successor state of the Ottoman Empire.

Syria was initially assisted by Iran, the preeminent Shi’a state in the Middle East, and by Russia, its most important ally outside the region. Hezbollah — the Lebanese militia supported by Iran — eventually contributed front-line troops to Syria.

At Iran’s request, Russian President Vladimir Putin greatly upgraded Moscow’s military aid to Syria, sending in aircraft and ground troops in 2015.

Russia’s intervention made a big difference. Before Russia stepped in, the Syrian government had lost about two-thirds of its territory to rebels. Since then, Syria has recovered a substantial part of it.

Idlib province, in the northwest, is still in rebel hands. Kurdish fighters, along with a modest contingent of U.S. soldiers, control much of northeastern Syria, the site of Syria’s oil fields. Islamic State fighters, having been driven out of their outposts in western Syria, have retreated to the eastern desert near the Iraqi frontier. Turkey, with American support, has established a buffer zone along stretches of its southern border with Syria.

Israel, Syria’s chief adversary, has been pulled into the fighting as well. Israel has bombed Syria’s artillery emplacements and bases in response to Syrian shelling from its side of the Golan Heights. Until about two years ago, Israeli field hospitals treated Syrians injured in battles.

In reaction to Iranian attempts to establish an anti-Israel front in Syria’s sector of the Golan, Israel has launched numerous air raids against Iranian sites in Syria. The Israeli Air Force has also struck Syrian missile batteries and Hezbollah arms convoys en route from Syria to Lebanon.

Israel and Russia have created a joint deconfliction committee to avoid unintentional clashes in the skies over Syria.

With the 10th anniversary of the civil war looming, Syria’s economy is in shambles. Its currency has all but collapsed. The price of basic goods, including food, has skyrocketed. Heating fuel is in short supply.

The World Food Program estimates that nearly two-thirds of Syrians are at risk of going hungry. “The socio-economic situation in Syria today is extremely difficult,” the Russian ambassador to Syria said recently.

The prospect of reconstruction is still far off, but the European Union has warned Assad that its sanctions will remain in place and that it will refrain from helping Syria rebuild its urban areas unless he resigns and fair elections are held, as called for by United Nations Security Council Resolution 2254.

“There will be no end to sanctions, no normalizations and no support for reconstruction until a political transition is underway,” Josep Borrell, the European Union’s top foreign affairs official, said recently.

The United States, which has sought Assad’s removal since the start of the civil war, is in full agreement with the policy of the European Union.

Syria, in the meantime, lies prostrate, bleeding profusely.