During Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs were displaced from their homes and fields in a catastrophe they refer to as the Nakba. Displacements occurred in towns such as Jaffa, Lod and Ramle.

Alon Schwartz’s eye-opening movie, Tantura, documents what happened in the Arab fishing village of Tantura, which was 35 kilometres south of Haifa and close to the Jewish settlement of Zichron Yaacov. It will be presented at this year’s Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 9-26.

Tantura, population 1,500, was included in the proposed Jewish state under the United Nation’s 1947 Palestine partition plan. When the first Arab-Israeli war broke out in 1948, a day after Israel declared independence, the Israeli army launched an offensive to conquer Tantura, which blocked the vital road from Haifa to Tel Aviv.

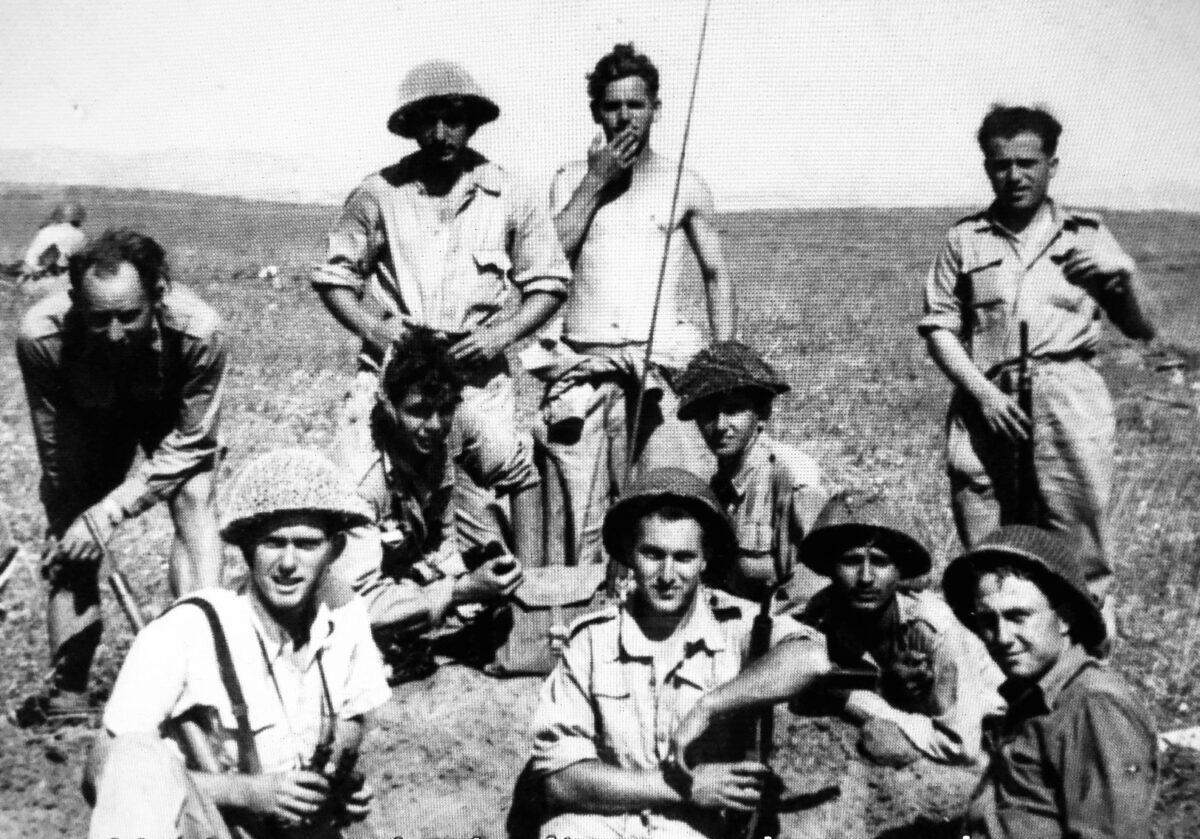

The Alexandroni Brigade captured the village on May 22, forcing many of its residents to flee. Three weeks later, a group of 63 Jews established Kibbutz Nachsholim on its grounds. The kibbutz is a thriving settlement today.

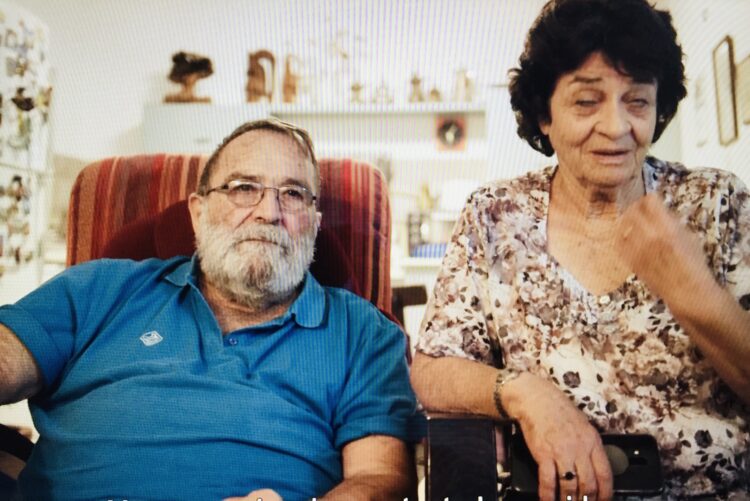

What occurred in Tantura following its surrender is at the core of Schwartz’s searing documentary. In the first scene, he introduces viewers to Yitzhak Pinto, 93, who, along with three women, are the last surviving original settlers. Later in the film, they discuss their diverse views about these events.

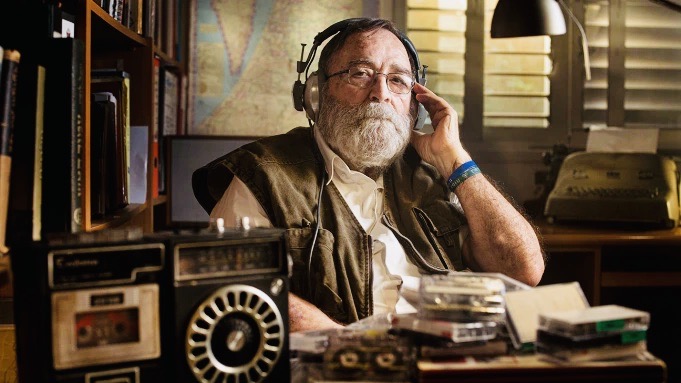

According to Teddy Katz, a resident of Kibbutz Nachsholim, Alexandroni Brigade soldiers committed war crimes in Tantura, driving out its inhabitants, killing some 200 Arabs and burying them in two mass graves. And by his reckoning, Arab women were raped.

Katz, a man in his 70s who has suffered multiple strokes and is in poor health, documented the atrocity in a Master of Arts history thesis submitted to Haifa University in 1998. The examiners were impressed, giving him an astonishingly high grade of 97 percent. Katz acquired much of his information from 135 Jews and Arabs who had witnessed the massacre and had agreed to be tape recorded. Katz amassed 140 hours of testimonies.

A journalist on the staff of the Maariv daily newspaper, having been tipped off about its explosive contents, wrote an article about the massacre. Once the details of Katz’s thesis came to light, there was a huge outcry among Israelis who either did not believe what had transpired or who sought to cover up the slaughter.

“All hell broke loose,” says Ilan Pappe, a former Haifa University historian critical of the Zionist movement.

Some veterans of the Alexandroni Brigade who had been interviewed by Katz recanted and sued him for defamation. Katz’s lawyer claims it was the first legal case in Israel to deal with the Nakba, which resulted in the dispossession of 750,000 Palestinians.

The controversy had a devastating impact on Katz. Haifa University compelled him to issue a letter of apology in which he retracted his claim concerning the massacre. Katz’s MA thesis was removed from libraries, cutting short his academic career.

Katz, who has been tarred as an “Israeli hater,” regrets having issued the apology, but he stands by his thesis. “There was a massacre,” he says emphatically. “Israeli soldiers killed many, many (Palestinians), and there was no reason to do it. We shot them for no reason.”

What occurred in Tantura was nothing less than ethnic cleansing, charges Pappe.

Hillel Cohen, a Hebrew University historian, accuses Haifa University of having silenced Katz. He believes the massacre was carried out because the Israeli government of Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion sought to eliminate the large concentration of Palestinians between Haifa and Tel Aviv.

In his interviews with veterans of the Alexandroni Brigade, Schwartz hears both sides of the story.

“You take a country by force,” says Haim Levin unapologetically. Another veteran adopts a radically different tone. “The village was eradicated,” he says flatly. A third veteran recalls witnessing a soldier shooting Arabs. An Arab bystander claims he saw 20 to 25 Arabs fatally shot.

“There was no tragedy like the tragedy at Tantura,” murmurs an elderly Arab woman who fled to the nearby Arab village of Fureides.

An Arab resident of Fureides believes that Israel should recognize the injustice and build a memorial in Kibbutz Nachsholim in honor of the victims. One of the original inhabitants of the kibbutz agrees with his recommendation.

Judging by the opinions of most of the Israeli veterans of the Alexandroni Brigade, the Tantura incident should be laid to rest once and for all. “There are things you don’t want to remember,” says one of the old soldiers. “I made myself forget.”