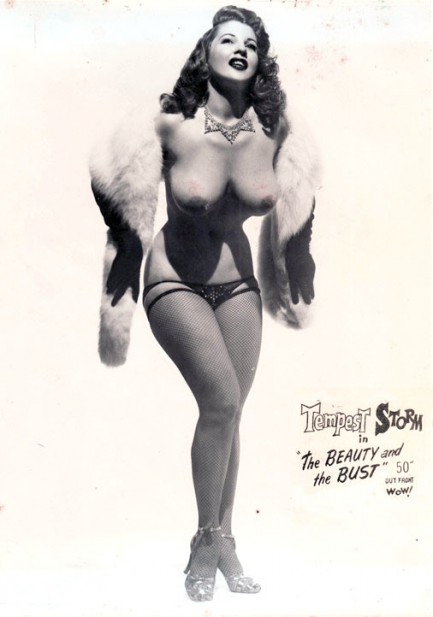

Nimisha Mukerji’s intriguing documentary, Tempest Storm, is a profile of a temptress from a bygone era.

The voluptuous lady who fits this description is Annie Banks, a “hurricane of seduction” who goes by the name of Tempest Storm. A sultry stripper who’s been dubbed the Queen of Exotic Dancing, she performs at burlesque festivals and attends autograph parties, rarely resting on her laurels.

Anatomically speaking, Tempest Storm is unusually endowed. With a 44DD/25/35 figure, long, flaming red hair and attractive features, she’s a specimen to behold. “I can’t identify with my age,” she coos.

Now 88, she’s a relic from the 1950s and 1960s. “No one has stayed in the business as long as I have,” she boasts in Tempest Storm, which opens in Canada on June 17. “I’m still the greatest,” she says begging the question why anyone might be interested in watching an octogenarian gyrate when porn and live streams with girls like Lori on cam are so readily available on the Internet.

The only exotic dancer ever to perform in Carnegie Hall, she’s been wowing men since she was a teenager fresh out of Eastman, Georgia, where she was born and raised. Sexually assaulted by her stepfather and gang raped by fellow high school students, she was 14 when she first tied the knot. Her first marriage lasted just two days, but her fourth and final fling at matrimonial bliss endured no less than 10 years.

Tempest Storm’s last marriage, to singer Herb Jeffries, caused an uproar because he was an African American. “To me, there was no color line,” she says. “But it was very dangerous for us to be together.”

Jeffries was a mulatto who could probably have passed for a swarthy southern European, but in Dwight Eisenhower’s America, even one drop of black blood was enough to consign a person to Jim Crow purgatory. Due to Tempest Storm’s marriage to Jeffries, her first manager quit, while Hollywood mogul Louis B. Mayer cut short her budding movie career.

Described as “a class act” by the film director Gary Marshall, she entered show business in Los Angeles and never really looked back. As Mukerji suggests, she turned to striptease to assert control over her destiny.

The secret of her success, apart from her body, was her aversion to cigarettes, alcohol and drugs. Smartly, she focused her attention on building a nest egg. “I was making big money,” she discloses. But because she was almost always on the road, she neglected her relationship with her daughter, causing a rift that has yet to heal.

Since she was the epitome of feminine beauty, Tempest Storm was never short of male company. She knew Elvis Presley intimately. “I taught him everything he knew,” she says wickedly without elaborating.

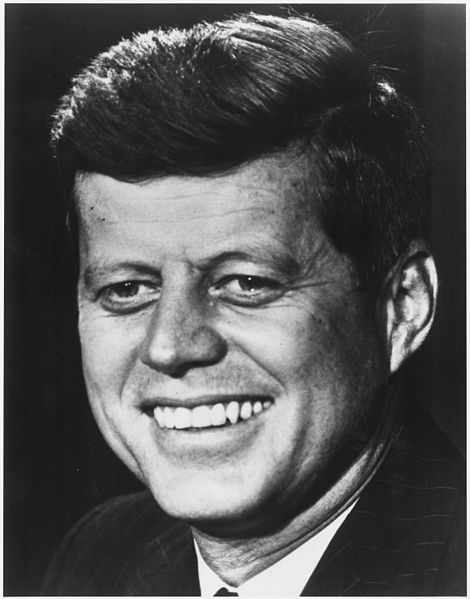

And she consorted with John F. Kennedy when he was a U.S. senator. They would meet at a hotel in Washington, D.C. for assignations. Coyly, she provides no further details, leaving it to our imagination to fill in the erotic gaps.

Through the course of the film, she flits from one place to the next — contacting her estranged daughter, meeting her two siblings in Georgia, visiting the cemetery where her biological father is buried, extolling the virtues of her current manager, Harvey Robbins, and basking in the praise of admirers from far and near.

“I’ve loved and lost and still have things to do,” she muses in a reflective moment, pretty much summing up the life and times of Tempest Storm.