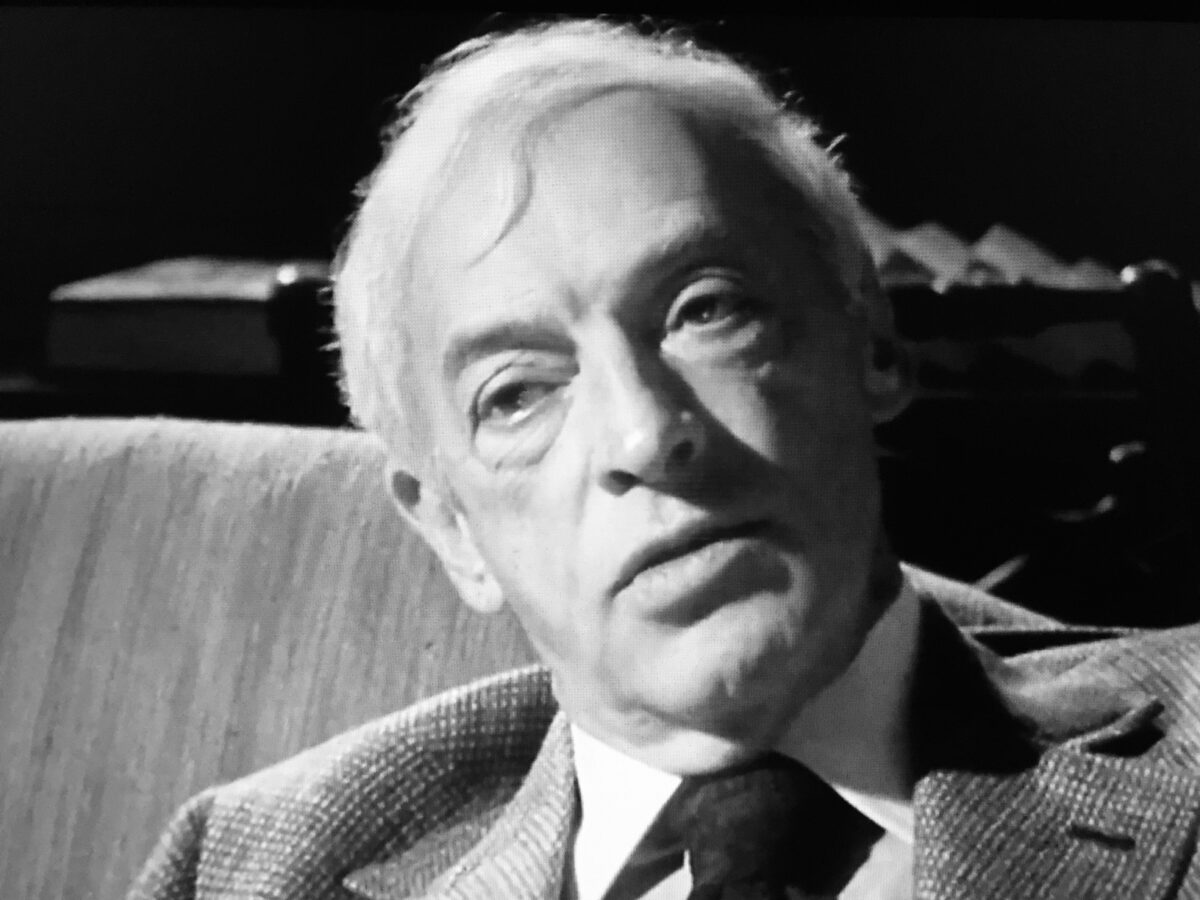

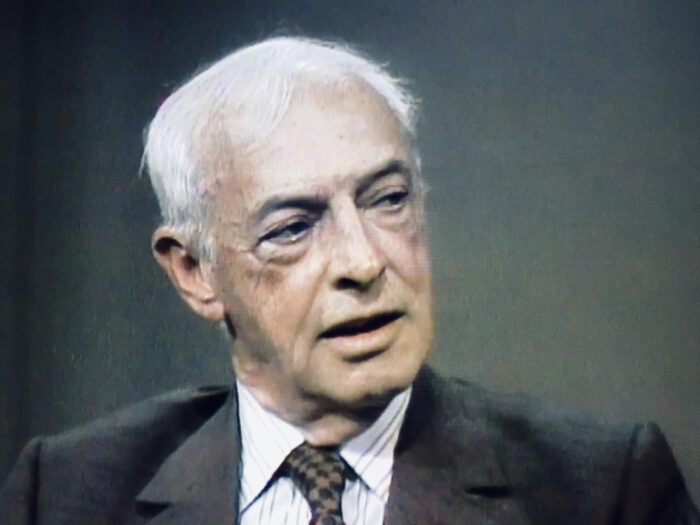

Saul Bellow was in the privileged and enviable position of knowing he was the most acclaimed American novelist of his generation. The winner of the 1976 Nobel Prize for literature, he was the author of critically praised novels that may yet stand the test of time: Seize the Day, Herzog, Mr. Sammler’s Planet, Ravelstein and The Dean’s December.

Bellow, who died in 2005, a few months short of his 90th birthday, is the subject of Asaf Galay’s fascinating biopic, The Adventures Of Saul Bellow. It will be screened online at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 3-13.

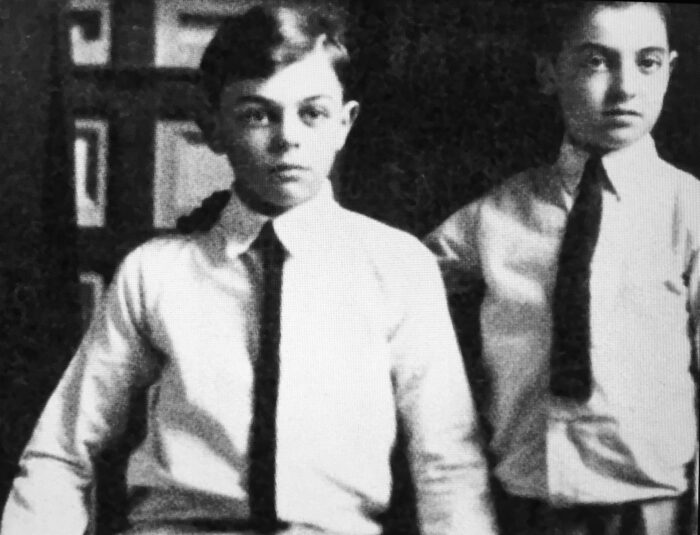

Galay, an Israeli, presents an impressionistic, mostly non-linear portrait of this giant. Born in the Montreal suburb of Lachine, the son of Lithuanian immigrants, he was raised in Chicago, a city where some of his novels are set.

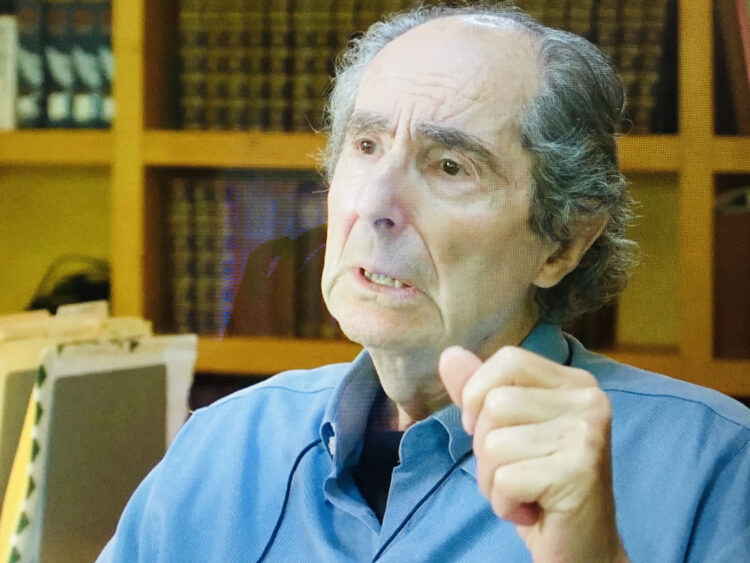

A procession of authors, ranging from Philip Roth to Salman Rushdie, offer succinct appraisals of Bellow that enhance the richness of the film. As Roth says, “The Adventures of Augie March changed my opinion of where a novel could go, of what a Jewish writer could do with his experience. I’m stamped with his prose and influence.”

In Rushdie’s view, Bellow mined the essence of Chicago to create an entirely self-contained universe.

Bellow’s sons weigh in with comments, too. One of them, Adam, remembers his father as a workaholic who sought refuge in his writing and wanted to be left alone.

An elegant prose stylist whose novels explored themes such as isolation, human awakening and spiritual dissociation, Bellow wrote with his soul rather than with his brain and heart, an observer says.

He grew up in a home where Russian, Yiddish and English were spoken. His father, a bootlegger, fled to the United States out of fear that Canadian police were hot on his trail. A philistine who could not understand his son’s literary ambitions, he thought Bellow was little more than “a schmuck with a pen.”

At university, his anthropology professor told him his essays were more like short stories than social science papers. Another professor, presumably an antisemite, said he was not born to English literature. Fortunately, Bellow disregarded his inane observation and went on to develop a prose style that incorporated the voices of unheard Americans into the highest levels of the language.

In the estimation of English literature professor Ruth Wisse, a fellow Montrealer, all of his novels brimmed with characters who resembled Bellow.

Politically, Bellow was a leftist in his youth, but after Europe’s disastrous bouts with Italian fascism and German Nazism, he grew to dread extremism and instability and became a conservative. Given his new outlook, he disliked the upheavals that rocked the United States in the 1960s.

The British novelist Martin Amis thinks he was unable to manage his love life. Judging by his five marriages, Amis’ comment may be true. “He liked to have a lot of ladies,” says a son.

One of his ex-wives, bedridden after injuring her ankle, fell in love with him after he read her excerpts from The Adventures of Augie March.

“My only wish was to make them happier than when I found them,” he says of the women he knew. “But I am not a social service agency,” he quickly adds.

His last wife, Janis Freedman, bore him a child, his only daughter, when he was 84 years old and five years away from death. Bellow was certainly a ladies’ man, but above all, he was a supremely talented writer.