Bernard Lewis, the eminent scholar of Middle East politics and religion, died on May 19. He was, for some 80 years, a towering scholar of Islam, and informed scholarly, governmental and popular audiences alike.

The outlines of his long career are well known. Born to Jewish parents in London in 1916, Lewis received his Ph.D. from the University of London in 1939. Among his professors were Sir Hamilton Gibb, the famous Arabist, and Norman H. Baynes, the historian of Byzantium.

After serving in the British army during World War II, Lewis became a professor of history at the School of Oriental and African Studies, part of the University of London, from 1949 to 1974. Subsequently, he was appointed professor of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University and a long-term member of the Institute for Advanced Study. He retired from Princeton in 1986.

The author of some 30 books and 200 articles, his studies have been translated into more than 25 languages. Most deal with Islamic history, chiefly Arab and Turkish, although he also translated poetry from Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, and Persian into English. He had gained renown as a pioneer researcher in the vast Ottoman archives in Istanbul.

Among his seminal works are The Arabs in History (1950); The Emergence of Modern Turkey (1961); The Muslim Discovery of Europe(1982); The Jews of Islam (1984); Semites and Antisemites (1986); The Political Language of Islam (1988); Islam and the West (1993); Cultures in Conflict: Christians, Muslims and Jews in the Age of Discovery (1995); The Multiple Identities of the Middle East (1998); and From Babel to Dragomans: Interpreting the Middle East (2004). He published his own memoirs, Notes on a Century, in 2012.

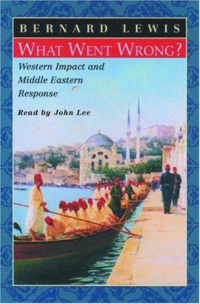

Most famous — and controversial — were the books What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response (2002), and The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror (2003).

Lewis was also notable for his public debates with the prominent Palestinian academic Edward Said, a humanities professor at Columbia University whose 1978 book, Orientalism, helped establish the academic field of post-colonial studies. Said once charged that Lewis was “dripping with condescension and contempt toward the Arab world.”

Decades of discord between Lewis and Said led to a famous debate between them in the New York Review of Books in 1982. Said contended that Lewis had an “extraordinary capacity for getting everything wrong” and accused him of “suppressing or distorting the truth.” Lewis responded by calling Said’s comments “an unsavory mixture of sneer and smear, bluster and innuendo, and guilt by association.”

As Lewis became more of a public intellectual, his enemies, many of them acolytes of Said’s, increased the level of criticism, calling him an Orientalist, a bigot, an advocate of western imperialism, and so on.

Lewis also withstood criticism for his stance that the slaughter of Armenians starting in 1915 did not meet the strict definition of “genocide.” He acknowledged the huge loss of life among ethnic Armenians in what was then the Ottoman Empire, but he insisted that there was insufficient evidence linking it directly to orders by Ottoman rulers

Martin Kramer, who teaches Middle Eastern history at Shalem College in Jerusalem and is a former student of Lewis, noted that Lewis, four decades ago, “foresaw the rise of radical Islam … and much else besides.”

Kramer was referring to “The Return of Islam,” an article Lewis published in Commentary magazine in January 1976. He predicted that Islam’s conflict with Christendom and the West would once again take center-stage in global politics, because each “recognized the other as its principal, indeed its only rival.”

Lewis argued the roots of the battle lay in the similarities at the core of the two faiths, distinguishing them from other major religions. “You had two religions with this shared ideology living side by side,” he told National Public Radio in 2012. “Conflict between them was inevitable.”

In a 1990 article for the Atlantic entitled “The Roots of Muslim Rage,” he warned that “we are facing a mood and a movement far transcending the level of issues and policies and the governments that pursue them. This is no less than a clash of civilizations” — a term that three years later was popularized by the Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington.

Lewis, therefore, considered the Israeli-Palestinian conflict only one of many struggles between the Islamic and non-Islamic worlds.

The Iranian revolution of 1979 had already helped transform Lewis into a well-known academic, because it made Washington pay attention to political Islam. After 2001, Lewis observed, “Osama bin Laden made me famous.”

Lewis harbored few illusions about the “Arab Spring” of 2011. “Many of our so-called friends in the region are inefficient kleptocracies. But they’re better than the Islamic radicals,” he told Jay Nordlinger, a senior editor at the National Review. Democrats, however, he added, are best of all — “and they do exist.”

Not that Lewis was infallible: For instance, in “The Revolt of Islam,” an article published in the New Yorker in November 2001, not long after the 9/11 attacks, he seemed to suggest that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein may have been implicated in the Al-Qaeda operation and that he had what Lewis called “unconventional” weapons. This, we now know, was untrue.

In an essay in The Wall Street Journal in 2002, Lewis wrote that in both Iraq and Iran, “there are democratic oppositions capable of taking over and forming governments,” and predicted that Iraqis would “rejoice” over an American invasion. These scenarios did not happen.

Lewis summed up his whole career this way: “For some, I’m the towering genius,” he told the Chronicle of Higher Education in 2012. “For others, I’m the devil incarnate.”

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.