Films reflect historical reality, registering the feelings and attitudes of an epoch.

As the American historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote,”The fact that film has been the most potent vehicle of the American imagination suggests all the more strongly that movies have something to tell us not just about the surfaces but about the mysteries of American life.”

Schlesinger’s observation can be transposed to the Jewish community in the United States. “Through movies, we can better understand America’s Jews and the changes in America that had an impact on (them),” writes Eric Goldman in The American Jewish Story Through Cinema, published by Texas University Press.

Goldman’s thesis can be summed up in a few words. When Jews were not as widely accepted in American mainstream society as they are today, Hollywood tended to downplay Jewish characters and themes. But with assimilation and acceptance, Hollywood moguls, many of whom were Jewish, grew more comfortable with portraying Jewish protagonists and experiences.

Goldman, a professor of cinema at Yeshiva University and the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City, begins with an examination of the silent era in Hollywood.

“Throughout the early years of cinema, the first decades of the 20th century, Jewish moviemakers focused largely on stories of successful assimilation into American society,” he observes.

Such assimilation, he notes, was often expressed through intermarriage. Films like The Cohens and the Kellys (1926) and Abie’s Irish Rose (1928) were representative of this genre. The first “talkie,” The Jazz Singer (1927), starring the irrepressible Al Jolson, hewed to this theme as well.

Clearly identifiable Jews disappeared from the screen following the rise of Nazism in Germany and the release of Darryl Zanuck’s The House of Rothschild (1934), he notes.

Goldman adds: “Even The Life of Emile Zola (1937) barely reveals that the accused Alfred Dreyfus, championed by Zola and a central figure in the film, is Jewish, despite the fact that his Jewishness is the key to understanding his plight.“

Warner Brothers` Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939), was a bold anti-Nazi film, the first of its kind to come out of Hollywood. But it was perceived by isolationists as a call for American involvement in European politics, an unpopular cause. Jewish producers, feeling the chill, pulled back and shelved screenplays about antisemitism.

Despite the climate of the day, Charlie Chaplin, a non-Jew, made The Great Dictator (1940), a spoof on Nazism and Adolf Hitler. “It took a non-Jew to have the courage to make such a film, as the comfort level for Jewish producers simply precluded any moviemaking on the subject,” Goldman says.

With the entry of the United States into World War II, Jewish characters reappeared in movies like The Purple Heart (1944) and Pride of the Marines (1945). “But the approach was still a cautious one, with Jewish characters … joining others of different ethnic origins and religions to fight America’s enemies abroad,” Goldman explains.

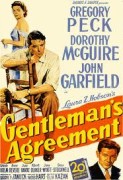

The Holocaust emboldened Zanuck, a non-Jew, to purchase the movie rights to Laura Hobson’s Gentleman’s Agreement, a novel about the scourge of antisemitism in the United States. Jewish leaders in Los Angeles attempted to dissuade Zanuck from making the film, fearing that calling attention to antisemitism would only inflame it.

Zanuck refused to give in to the pressure, and production on Gentleman’s Agreement proceeded. Released in 1947 and starring Gregory Peck as a gentile masquerading as a Jew, it won the Academy Award for best motion picture. Goldman delves deeply into the making of this ground-breaking movie, and his treatment of the topic is the best thing about The American Jewish Story Through Cinema.

Interestingly enough, Gentleman’s Agreement was not the only movie of 1947 that dealt with antisemitism. Crossfire, a low-budget film, was the eighth-highest grossing film of that year.

During the 1950s and 1960s, a few producers turned to the Holocaust and Israel. The Juggler, starring Kirk Douglas and set partially in Israel, appeared in 1953. The Diary of Anne Frank, shorn of much of its Jewish content, reached theaters in 1959. Otto Preminger`s Exodus, starring Paul Newman as an Israeli fighter, came out in the early 1960s.

In Goldman`s judgment, Goodbye, Columbus, adapted from a novel by Philip Roth, signified something important: “The Jew in America had finally arrived socio-economically..”

Films such as The Heartbreak Kid (1972) and Hearts of the West (1975), he adds, attested to the growing stature of American Jews. Goldman claims that Sydney Pollack’s The Way We Were, featuring Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford, exemplified this trend in fimmaking, as did Yentl, adapted from Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Yentl the Yeshiva Boy. Barry Levinson’s Avalon (1990) and Liberty Heights (1999) were also part of this process.

Goldman argues that Woody Allen has struggled on screen with his Jewish identity, citing films like Sleeper (1973), Annie Hall (1977) and Zelig (1983).

Goldman concludes with an analysis of Everything is Illuminated (2005), drawn from Jonathan Safran Foer’s novel of search for one’s ancestral roots in eastern Europe.

On balance, The American Jewish Story Through Cinema is a competent work of scholarship. But it could have been better had Goldman tightened his sprawling writing style.