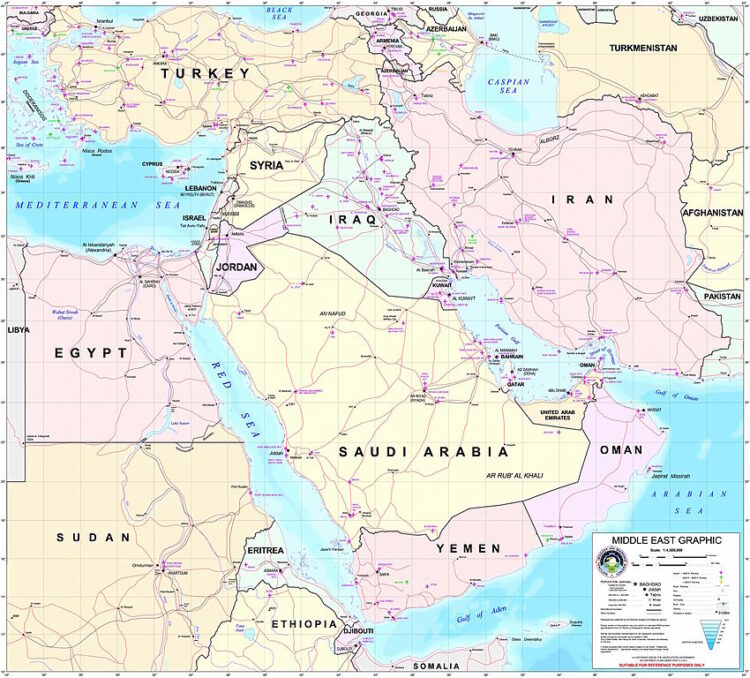

The grassroots revolts that erupted in the Arab world from 2010 onwards, widely known as the Arab Spring, held out the tantalizing promise of positive transformation in the Middle East.

“For the first time, mass movements of ordinary people sought to take their political fate into their own hands and shape a better future for themselves,” writes Noah Feldman in The Arab Winter: A Tragedy (Princeton University Press).

These uprisings began in Tunisia and swept through Egypt, Libya, Syria and Yemen, bringing upheaval, bloodshed and disappointment. The Arab Spring, a mirage and a false dawn, led to the Arab Winter.

Several dictators, ranging from Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak to Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi, were removed peacefully or by force, but the common people in the forefront of the popular uprisings never achieved a scintilla of power.

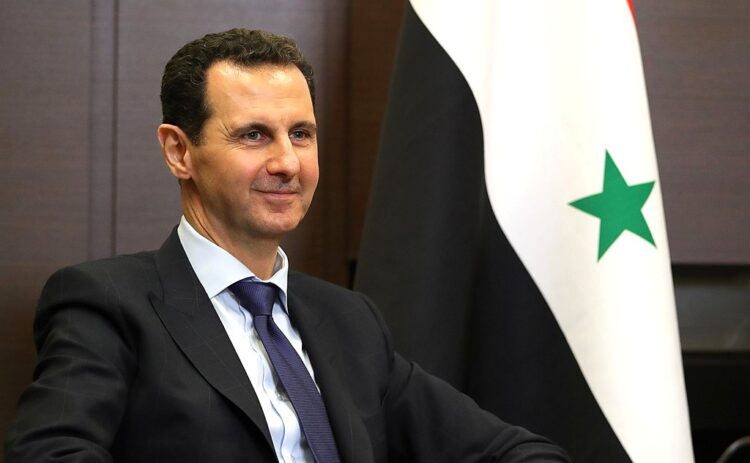

In Egypt, Abdel Fattah el-Sissi, the minister of defence, deposed a democratically-elected president, Mohammed Morsi, and established yet another dictatorship. In Syria, President Bashar al-Assad struck back ferociously, triggering a civil war that still rages on. And in Libya and Yemen, civil wars erupted as well. Tunisia was affected by the chaos, but it managed the transition quite successfully.

The energies released by the Arab Spring gave rise to the Islamic State organization, which seized large swaths of territory in Syria and Iraq and launched terrorist attacks in the Middle East, Asia and Europe.

Feldman, a professor of law at Harvard University, acknowledges that the Arab Spring failed to achieve most of its grander aspirations and ultimately made many people’s lives worse than before.

But he argues that it marked a new and unprecedented phase in Arab political experience. “The Arab Spring demonstrated the existence of a trans-national sense of cross-border political identification,” he says. Its participants engaged in collective action for self-determination rather than for anti-colonial objectives. Feldman’s third claim is that political Islam was transformed by the Arab Spring.

Feldman believes that the protesters who took to the streets to demand change sought an end to “presidential dictatorships,” which were built on an intricate combination of military power, secret services and statist market economies.

Protesters in Jordan and Morocco called for constitutional reform rather than wholesale change because they did not question the legitimacy of these monarchies.

Nowhere did the term “democracy” figure as a major demand, he notes. What the protesters desired was freedom, dignity and social justice, even though the regimes they opposed offered them food subsidies, employment in state enterprises and low-cost education.

Feldman, in his study, focuses on three countries — Egypt, Syria and Tunisia.

Protesters in Egypt played a greater role in bringing down Mubarak and then Morsi than the armed forces, which had much to gain from removing him. “The greatest prize was massive institutional legitimacy,” says Feldman. “If the army appeared to be acting at the behest of the people, it would consolidate the belief that the army was uniquely the only institution that was serving the people’s interests.”

Feldman contends that Morsi, a high-ranking official from the now-banned Muslim Brotherhood, committed a “historic error” by not coopting secular and liberal allies. “Had Morsi and the Brotherhood shared power rather going it alone, they still might not have survived. But their odds of survival would have been far greater.”

In Feldman’s view, the fundamental cause of the violence in Syria was rooted in the disempowerment of the Sunni majority by the Alawi-dominated Assad regime. Challenges to Assad’s regime were regarded as existential threats to Syria’s minority Alawis, who comprise 15 percent of the population.

“The Arab Spring brought war to Syria because the regime and the protesters alike quickly entered a dynamic in which both sides rejected compromise in favor of a winner-take-all struggle for control of the state,” he says.

Alawis identify ethnically as Arabs and religiously as Muslims, but in order to avoid persecution they created “a culture of inward-looking solidarity based on secrecy, mutual loyalty, and distrust of outsiders,” Feldman states.

Alawis gravitated toward Baathism, Syria’s dominant political ideology since the early 1960s, because it promised them full citizenship on equal terms with Sunnis. But after the eruption of the uprising in Syria in 2011, Assad portrayed it as a Sunni movement against the Alawis. The army’s officer corps, mostly composed of Alawis, rallied behind Assad.

Assad might have lost the war if not for Russian intervention and military assistance from Iran and Hezbollah. Feldman believes that the American approach to Syria was muddled. “To put it bluntly, U.S. policy was to strengthen the forces threatening the regime enough to keep them in the fight, while refusing to take definitive steps that would make them win.”

“The result, intentional or otherwise, was to prolong the civil war indefinitely,” he adds.

Feldman thinks that a “massive air campaign” by the United States, modelled after the one carried out in Libya, would likely have succeeded in ousting Assad.

Feeldman is scathing in his criticism of Islamic State, whose version of political Islam was decidedly illiberal and non-democratic. Islamic State arose in Iraq and spread to Syria, and for a while its caliphate in these countries functioned like a state.

The combination of Western air power, Kurdish and Shi’a militias and Russian air and ground support of the Syrian government ended Islamic State’s run of good luck, he says.

Its virtual demise in Syria and Iraq has had consequences. “Political Islam is now left without a noteworthy model of a state form that might actually work,” says Feldman. “Political Islam stands more discredited than at any time in the past century.”

Tunisia is the only success story of the Arab Spring. “Contrasted with the failure of Egypt and the disaster of Syria, Tunisia looks like any extreme outlier in the broader, regional phenomenon that it started.”

Tunisian President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali was the first Arab ruler to be sent packing. He left the country on January 14, 2011. After his departure, secular and Islamic activists, civil society institutions, new politicians and the public engaged in what Feldman describes as a “slowly evolving, high-stakes process of negotiation and compromise that led to the emergence of a relatively stable, functioning, constitutional liberal democracy.”

Feldman credits Tunisia’s good fortune to, among others, Rached el-Ghannouchi, the leader of its largest Islamist party who guided Tunisia into “a remarkable synthesis of Islam and liberalism.” Ghannouchi’s combination of intellect, character and leadership were absent in the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and particularly in Morsi, he says.

What ultimately happened in Tunisia was astonishing.

“The protesters went to the streets seeking jobs and social justice, believing that regime change would bring both. What they got was a constitutional democracy with elected politicians.

“Taken on its own, the story of Tunisia is not a tragedy but a moving chapter in both the inspirational and quotidian realties of self-government. To have created the first functioning Arab democracy is a generational, historic achievement.”

This is particularly true in light of the fact that the Arab Spring produced little more than blood and tears elsewhere in the Middle East.