Jews in Palestine were not handed political sovereignty on a silver platter. Not by a long shot. As Bruce Hoffman observes in Anonymous Soldiers: The Struggle For Israel, 1917-1947 (Alfred A. Knopf), they achieved statehood through diplomacy and civil disobedience but above all through armed resistance and terrorist violence.

In this magisterial account, told mostly through the eyes of the British officials and soldiers who administered Palestine for some 30 years under a League of Nations mandate, Hoffman suggests that the Yishuv — the Jewish community of Palestine — could not have attained this objective without bloodshed.

Hoffman’s narrative begins with the arrival in Palestine of British general Edmund Allenby in 1917. Allenby, who had been singularly unsuccessful in breaking through German lines in Europe, acquitted himself better in the Middle East, defeating Turkish forces in the Gaza Strip and Beersheba. Following his triumphant entry into Jerusalem, he resumed his offensive near Megiddo, routing the Turks yet again and forcing them to surrender. As Hoffman reminds a reader, Allenby’s conquest of Palestine in 1918 ended four centuries of rule by the Ottoman Empire.

The British era got off to a bumpy start due to irreconcilable commitments made by the British government during World War I. In the McMahon-Hussein agreement, Britain promised to support Arab self-determination in areas vacated by the Ottomans. And in the Balfour Declaration, Britain came out in favour of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine.

Throughout the first decade of the British mandate, Palestine flourished and festered. As the population grew and the economy expanded, Arab violence exploded, prompted by fears that Jewish political and economic domination would lead to the loss of their lands. The Arabs, who outnumbered Jews by a substantial margin, demanded an end to Jewish immigration, a ban on Jewish land purchases and the creation of a democratic state based on proportional representation.

“Arab disquiet would henceforth neither abate nor be sated by anything short of Britain’s unambiguous disavowal of the Balfour Declaration,” writes Hoffman, an American scholar at Georgetown University.

The Arab revolt, which unfolded between 1936 and 1939, was rooted in Palestinian Arab dissatisfaction with the status quo. The rebellion, which posed a direct challenge to Britain and a dire threat to the Yishuv, manifested itself through urban riots and general strikes before becoming a fullblown guerrilla war. During this turbulent period, Hoffman notes, the mantle of Arab leadership passed from the traditional ruling elite to the new generation of radicalized youths.

David Ben-Gurion, one of the leading figures in the Yishuv, was convinced that Jews should abide by the Haganah’s long-standing policy of havlaga (restraint). The Haganah was the mainstream Jewish fighting force in Palestine. The Irgun, the military arm of the Zionist Revisionist movement, did not observe such niceties. It launched a series of attacks against the Arabs, eliciting condemnation from official Zionist organizations and newspapers.

With bloodshed consuming the country, a British royal commission recommended partition as a solution. As Hoffman points out, the British Foreign Office opposed partition on the grounds that it could only be imposed by force. Vehemently rejected by the Arab side as well, the plan was grudgingly accepted by the Yishuv.

Violence continued to flare, compelling Britain to reinforce its garrison and to strike hard at Arab marauders. With Europe edging closer to war, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain shocked the Yishuv by enunciating a pro-Arab policy. “If we must offend one side,” he said, “let us offend the Jews rather than the Arabs.”

Chamberlain’s comment was a precursor to the White Paper, issued by Britain in May 1939. Calling partition “impracticable,” it recommended that Palestine should remain a unitary entity and be granted independence after a 10-year transitional period, that Jewish immigration should be strictly regulated and that Jewish land purchases should be subject to restrictions.

The Irgun’s reaction was swift in coming. Throughout the following month, it struck British and Arab targets alike. But with the outbreak of World War II, the Irgun announced a suspension of all operations. The Yishuv, meanwhile, offered support for the British war effort while continuing to press for the repeal of the White paper. As Ben Gurion famously put it, “We will fight with Great Britain in this war as if there was no White paper, and we shall fight the White paper as if there was no war.”

Lehi, an extremist faction which had broken away from the Irgun, dissented from this position, announcing a policy of non-cooperation with the British and official Zionist institutions. Lurching further into the wilderness, Lehi attempted to form ties with fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, a bizarre episode that Hoffman describes at some length.

The Irgun, now under the command of a newly arrived Polish Jew named Menachem Begin, switched course in the winter of 1944, declaring “there can no longer be an armistice between the Jewish Nation … and a British administration in the Land of Israel …” Irgun fighters attacked British civil and police sites and tried to assassinate the British high commissioner, Harold MacMichael, one of the architects of the White Paper.

These attacks infuriated the Zionist establishment, which endorsed British efforts to stamp out Irgun terrorism. Lehi’s assassination of Lord Moyne, the Cairo-based British minister of state in the Middle East, redoubled the Yishuv’s determination to cooperate with the British authorities.

As Hoffman observes, the election of a Labor Party government in Britain in 1945 inflamed the situation. In opposition, Labor had been sympathetic to the Zionist movement and had staunchly opposed the White Paper. Once in power, Labor performed a volte face. The new prime minister, Clement Attlee, and the foreign minister, Ernest Bevin, disappointed the Yishuv by endorsing the White Paper.

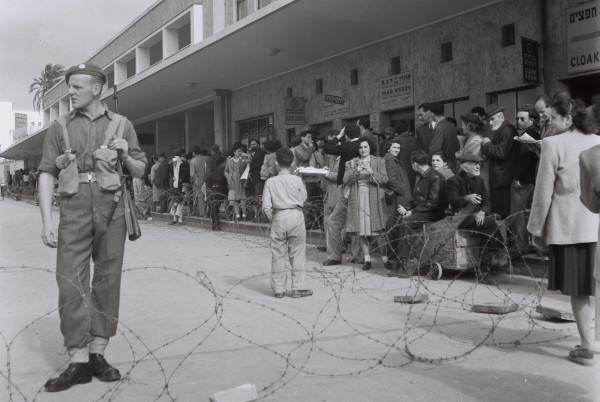

Stung by this betrayal, the Haganah, Irgun and Lehi formed an informal alliance and carried out joint operations. Unlike the Arab rebellion, the Jewish revolt was predominantly urban in nature, with fighters embedding themselves in the Jewish community. Assessing the violence, a senior British official concluded that, in the absence of “a firm, consistent policy,” Arabs and Jews “had been encouraged to feel that by agitation, by terrorism and by propaganda … they can always swing the pendulum over to their side.”

Alan Gordon Cunningham, the last British high commissioner in Palestine, believed the Yishuv should be brought to heel. But his colleague, General Evelyn Barker, cautioned that a “virile and intelligent people like the Jews could not be subjugated by force.” With tensions rising following the Irgun’s bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, which killed 91 people, Barker changed his tune. In an antisemitic jibe, he said that Jews should be punished by “striking them at their pockets and showing our contempt for them.”

Bevin’s proposal for a unitary, binational state in Palestine under United Nations trusteeship outraged the Yishuv. But Bevin’s idea was rendered irrelevant by a report from the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine unanimously recommending that the British mandate should be terminated and that Palestine should be granted its independence as soon as possible. Shortly afterwards, the United Nations General Assembly voted for partition.

British rule ended on May 15, 1948. In Hoffman’s view, Britain gave up Palestine for a number of reasons. British officials finally concluded that the differences between Jews and Arabs could not be bridged. Britain, sapped by World War II, could not afford to keep an army of 100,000 soldiers and police stationed in Palestine. The British government had come under intense American pressure to rescind the White Paper.

Hoffman contends that Jewish terrorism, which fostered a sense of hopelessness and despair, played a “salient role” in Britain’s decision to vacate Palestine. “Britain never really had a firm or consistent policy for Palestine,” he adds. “This, in turn, rendered successive British governments susceptible to terrorist pressure. The impression shared by Arab and Jew was that London could be influenced, intimidated or otherwise persuaded by violence.”

As Cunningham complained, the prevailing belief was that “England always gives in to force.”

In the final analysis, says Hoffman, “Britain’s commitment in Palestine exceeded not only its financial resources but, most important, its will to remain there whether for reasons of prestige or strategic considerations.”