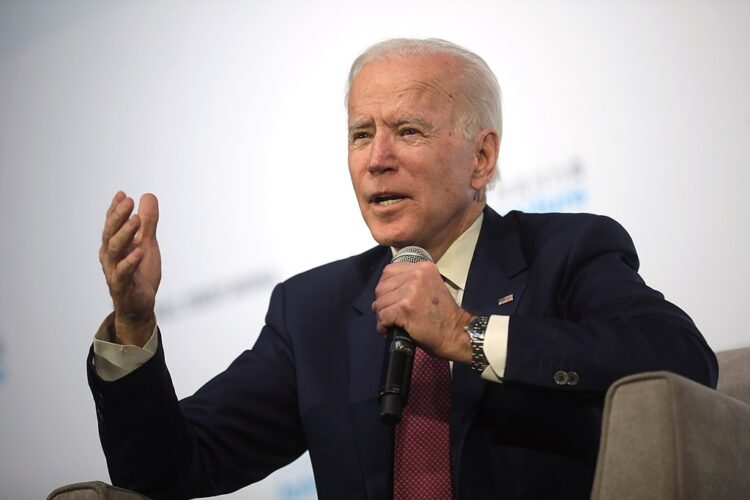

Joe Biden bit the bullet on April 24 and acknowledged what no previous U.S. president had ever dared to boldly state in public: the mass murder of Christian Armenians in the Ottoman Empire about a century ago was nothing less than genocide.

Much to Turkey’s chagrin, 30 countries, ranging from Canada and Germany to Argentina and Russia, had already recognized the killing of 1.5 million Armenians as genocide.

In the wake of Biden’s announcement, Israel’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement recognizing the “terrible suffering and tragedy” of the Armenians. The ministry stopped short of defining their terrible fate as genocide. Israeli diplomats were obviously concerned that Israel’s frayed ties with Turkey may unravel further if the Israeli government follows Biden’s lead.

Some Israeli politicians, notably President Reuven Rivlin and Yair Lapid of the centrist Yesh Atid Party, believe that Israel — a haven for Holocaust survivors — has a moral obligation to officially recognize the Armenian genocide. In 2011, the Knesset allowed an open discussion of it for the first time, but no resolution was passed.

Until now, the United States was reluctant to take that giant leap, fearing it would offend Turkey, one of its principal allies in the Middle East. President Ronald Reagan came close in 1981 when, in a speech commemorating the Holocaust, he made a passing reference to the “genocide of the Armenians.”

But apart from this fleeting remark, not a single American president after Reagan had the temerity or the courage to challenge official Turkish dogma that the mass slaughter of Armenians could not be described as genocide.

Turkish leaders admit that widespread atrocities took place, particularly between 1916 and 1916, but adamantly deny that the massacres fall under the broad category of genocide.

So it was hardly surprising that Biden’s statement, issued on the 106th anniversary of the start of the killings, stirred anger in Turkey.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan denounced his recognition as “groundless” and warned it had opened a “deep wound” in bilateral relations, which are strained over a plethora of contentious issues.

Turkey’s foreign minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, was just as indignant. “Words cannot change or rewrite history,” he wrote on Twitter. “We have nothing to learn from anybody on our own past. Political opportunism is the greatest betrayal to peace and justice. We entirely reject this statement based solely on populism.”

The Turkish foreign ministry accused the United States of mangling historical facts and charged Biden with undermining “our mutual trust and friendship.” The ministry urged the Biden administration “to correct this grave mistake.”

It is extremely unlikely that the United States, which is home to a substantial Armenian community, will heed Turkey’s advice. The die has been cast.

Biden’s declaration was in keeping with his abiding belief that human rights must be a pillar of U.S. foreign policy. His predecessor, Donald Trump, had a fairly good relationship with Erdogan, but because they were at odds over two key issues, he imposed sanctions on Turkey. Nevertheless, he shied away from declaring the mass murder of Armenians as genocide.

Biden felt no such compunctions. In the past few years, U.S.-Turkish relations have deteriorated to such an extent that he could see no risk in breaking with American policy on the Armenian question.

Turkey, the sole Muslim member of the NATO alliance, alienated the United States and its allies by purchasing the S-400 missile defence system from Russia in 2017. By way of retaliation, the Trump administration halted the delivery to Turkey of the state-of-the-art F-35 stealth aircraft, which has been sold to Israel and Australia, among other Western nations.

In the wake of the failed 2016 coup, which some Turks blamed on American machinations, Turkey demanded the extradition of Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen, who lives in exile in the United States. Erdogan, once Gulen’s close friend, claimed he had masterminded the coup from his home in Pennsylvania. Much to Turkey’s anger, Washington declined to extradite Gulen.

The United States and Turkey have also been at loggerheads over its armed incursions into northern Syria, which has been embroiled in a civil war since 20011.

Given Turkey’s substantive differences with the United States, some critics have accused Erdogan of steering Turkey away from the West and into Russia’s orbit. Turkey, however, remains a vital cog in NATO, allowing its Incerlik air base to be used by the United States.

Turkey, too, hosts several million Syrian refugees, though the cost of this hospitality is borne by Western industrial countries to the tune of billions of dollars. If Turkey expelled the Syrians, they would surely head for Europe, a prospect European leaders would find most unpalatable.

Biden took all these factors into account before personally informing Erdogan of his decision to recognize the Armenian genocide, which was well documented by foreign diplomats and missionaries.

Framing it as his administration’s commitment to human rights, he said, “Each year on this day, we remember the lives of all those who died in the Ottoman-era Armenian genocide and recommit ourselves to preventing such an atrocity from ever again occurring. We remember so that we remain ever vigilant against the corrosive influence of hate in all its forms.”

In a comment designed to soothe Turkey’s ruffled feathers, he added, “We affirm the history. We do this not to cast blame, but to ensure that what happened is never repeated.”

Deborah Lipstadt, a professor of modern Jewish history and Holocaust studies at Emory University and the author of books on Holocaust denial and antisemitism, commended Biden for his principled approach to this highly sensitive topic.

“The Armenian genocide has been too long denied, diminished in importance or politicized,” she said. “This is a step in rectifying that. It comes too late for those who experienced this horror, but it will be a bit of a balm to their children, grandchildren and other descendants.”

By the early 20th century, the once mighty Ottoman Empire had been vastly reduced in size and influence by separatist rebellions and costly wars in southern Europe. With the outbreak of World War I, the Ottomans, aligned with Germany, faced threats from the east and the west from the Russian Empire and Britain.

The Committee of Unity and Progress, comprised of Turkish army officers who had seized power in 1908 in the name of the Young Turk movement, regarded the Armenian community as a pro-Russian fifth column. Concentrated mainly in eastern Anatolia and consisting of 2.1 million people, Ottoman Armenians were a vulnerable minority who had been the object of pogroms in the 1890s and 1909.

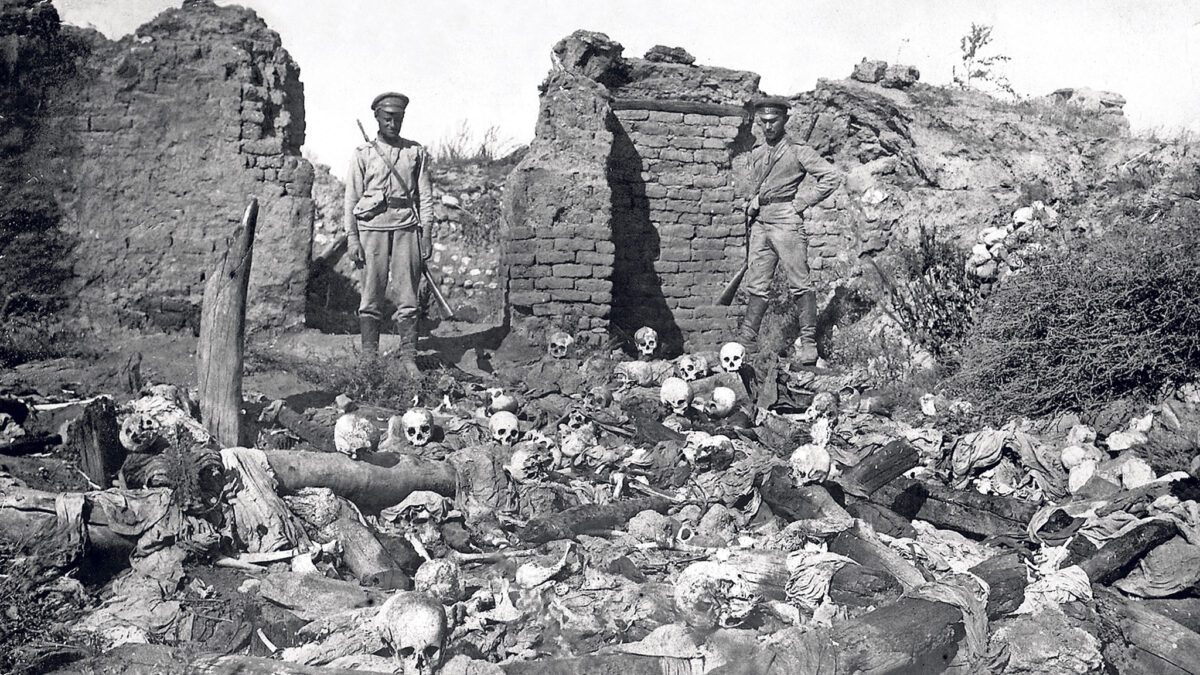

On April 24, 1915, a few hundred Armenian intellectuals who had come under suspicion were rounded up and executed. With the community at large considered a security threat, Armenian men, women and children were deported, marched across the Syrian desert where many died of starvation and exhaustion. Still others were summarily shot. Some Armenian girls were spared on condition they converted to Islam.

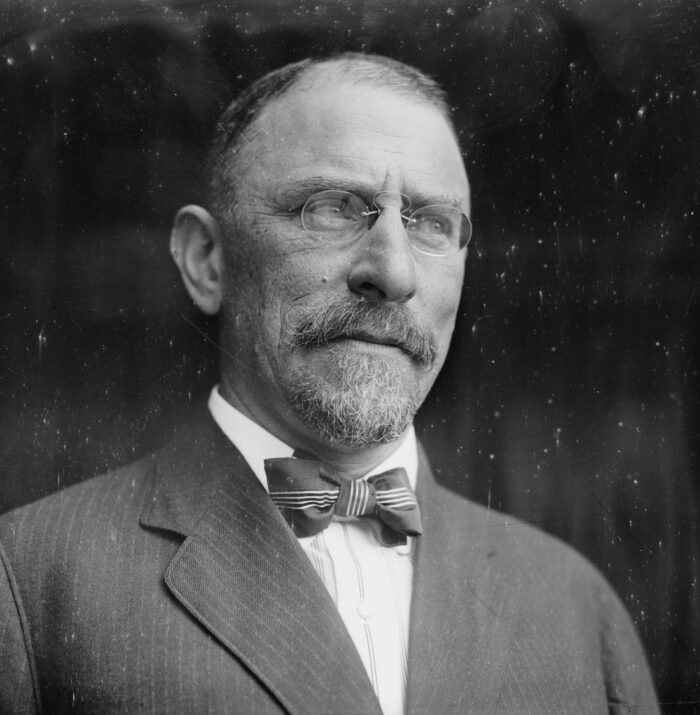

Henry Morgenthau, the U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, wrote a damning cable in 1915: “Reports from widely scattered districts indicate systematic attempts to uproot peaceful Armenian populations and through arbitrary arrests, terrible tortures, wholesale expulsions and deportations from one end of the empire to the other accompanied by frequent instances of rape, pillage, and murder, turning into massacre, to bring destruction and destitution on them. These measures are not in response to popular or fanatical demand but are purely arbitrary and directed from Constantinople in the name of military necessity, often in districts where no military operations are likely to take place.”

Aghast at the wholesale slaughter of Armenian civilians, The New York Times condemned the “policy of extermination directed against the Christians of Asia Minor.”

By 1922, a year before the emergence of Turkey as the Ottoman Empire’s successor state, 387,000 Armenians still lived there. Since then, virtually all of Turkey’s Armenian citizens have emigrated.

Denying that the atrocities can be equated with genocide, Turkish spokesman have argued there is no evidence that it was planned in advance.

True or not, the bottom line remains the same. As Morgenthau wrote in his memoirs, “When the Turkish authorities gave the orders for the deportations, they were merely giving the death warrant to a whole race. They understood this well, and in their conversations with me, they made no particular attempt to conceal the fact.”

Genocide, as generally defined, refers to the deliberate murder of a large number of people from a distinctive national, ethnic, racial or religious group. The word was coined by the Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in his book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, published in 1944, when several hundred thousand Hungarian Jews were murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Lemkin’s definition, adopted by the United Nations after World War II, can be applied to the Rwandan massacre of the Tutsi minority in 1994. But does this universally accepted definition apply to the Ottoman killing of Armenians?

The International Association of Genocide Scholars passed a resolution in 1997 unanimously recognizing the mass murder of the Armenians as genocide. In 2015, the European Parliament reached a similar conclusion

But can one compare the Holocaust with the Armenian genocide?

Nazi Germany, in its maniacal and systematic zeal to murder the Jews of Europe in the Final Solution, slaughtered as many Jews as it could possibly lay its hands on. The Ottoman Empire, though guilty of crimes against humanity, did not kill every Armenian within its jurisdiction. Nor was that its intention.

That’s an important difference to remember.

Adolf Hitler, in preparation of Germany’s impending invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, told army commanders on August 22 that his war aims included the “physical destruction of the enemy” so that Germans could acquire additional “living space.” The “enemy,” in his diabolical estimation,” consisted of “men, women and children of Polish derivation and language.”

He ended his thunderous speech with these taunting words: “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians.”

Hitler, of course, was ultimately wrong. The Ottoman mass murder of Armenians faded into the landscape of history and was almost forgotten by everyone but the Armenians themselves. But much to Turkey’s distress, this emotive issue has been stunningly revived by the president of the United States, and more nations will probably follow suit in recognizing the Armenian genocide.