It’s amazing to think that it has been 80 years since the famous Battle of Cable Street, which took place on October 4, 1936 in London’s East End, where most of England’s Jews lived at the time.

I say this because when I began researching my PhD dissertation on London Jews and British Communism in 1975, it was still fresh in people’s memories.

I interviewed many of the participants in the late 1970s. I wonder how many of them are still alive?

Sir Oswald Mosley, the British fascist leader who provoked the event, himself died 36 years ago.

Originally a rising star in the British Labour Party, Mosley had founded his British Union of Fascists (BUF) in 1932. Soon enough, marching through London in their Blackshirt uniforms, Jew-baiting and antisemitism became the mainstay of their activities.

By 1936, Blackshirt attacks on Jews had become a major problem. Many East End Jews considered the response of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, the community’s umbrella defence organization, as not being militant enough.

In response, the Jewish People’s Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism (JPC), set out, as its name suggested, to combat not only prejudice against Jews, but also the political movement seen as primarily responsible for it, fascism.

The BUF had announced its intention to march through the East End on October 4. Outraged, in particular that many areas of high Jewish population were on the proposed route, the JPC, led by Communists, began to organize opposition to Mosley’s plans.

Initially, the JPC attempted to persuade the authorities to prevent the event taking place altogether, gathering almost 100,000 signatures in the space of two days in support of a petition to prohibit such marches.

Their demands were, however, rejected by the government, on the grounds that prohibiting the procession would constitute a restriction of freedom of speech and would allow Mosley to portray himself as a victim.

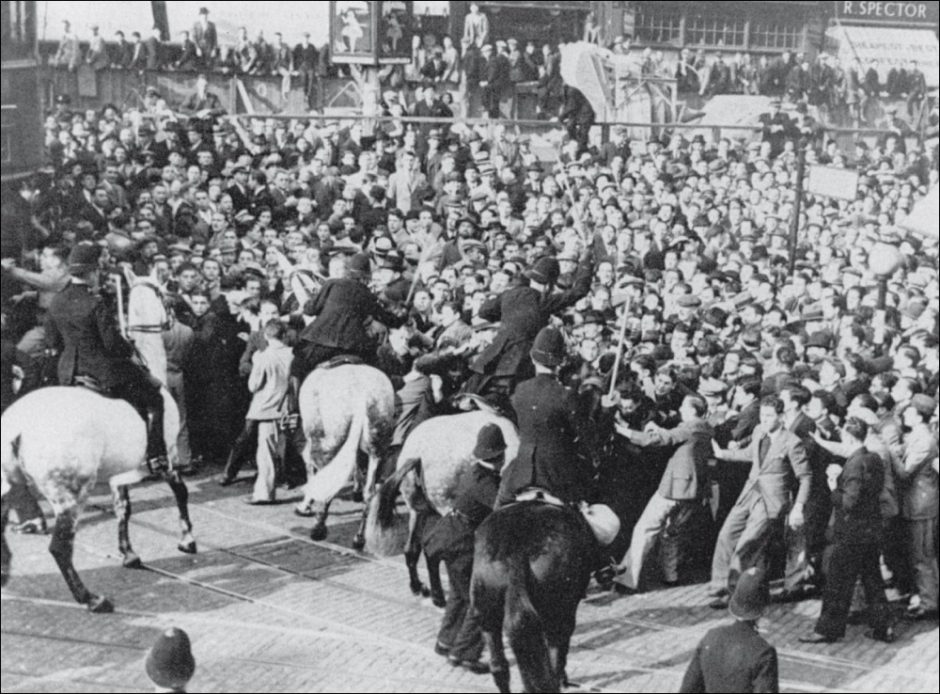

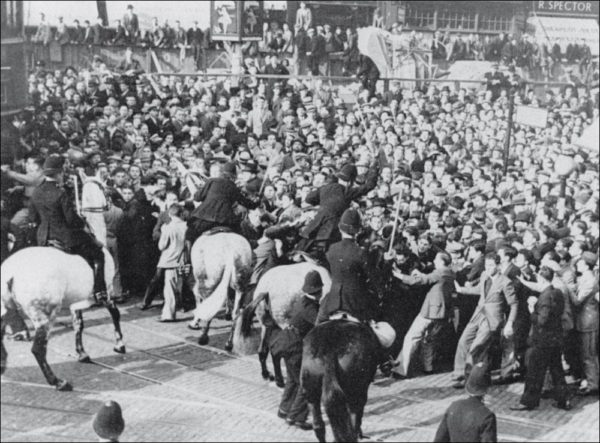

On the day of the march, a crowd of at least 100,000 protestors congregated in the East End to prevent the passage of Mosley’s column of Blackshirts, who were only a couple of thousand strong. Around 6,000 police officers were deployed to keep the two sides apart, and to clear a path for the marchers.

But in the face of determined, and often violent, resistance from the demonstrators, the authorities advised Mosley to call off the procession, which he agreed to do. Even so, some 80 protestors were arrested, and 73 police officers injured.

At Cable Street itself, the widespread adoption of the Spanish Republican slogan of no pasaran (they shall not pass) as a rallying call was a telling indication that the event was seen to transcend its East End setting, because that was also the slogan of the Spanish Republicans fighting against Francisco Franco’s fascists in that country’s civil war.

Some Anglo-Jewish historians have described the Battle of Cable Street as the most remembered day in twentieth century British Jewish history.

One of the prime Communist organizers of the battle against the BUF at Cable Street, Phil Piratin, would go on to be elected a member of parliament from the area in 1945.

As for Mosley, with the coming of World War II, he and many BUF members were interned, and the BUF banned.

He was released in 1943, but, politically discredited by his association with fascism, he moved abroad in 1951, spending most of the remainder of his life in France. He was never again a significant danger to the Anglo-Jewish community.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.