Who betrayed the celebrated Dutch Jewish diarist Anne Frank? That’s the burning question Canadian historian Rosemary Sullivan addresses in her deeply-researched, probing book, The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation (HarperCollins).

Anne and her family, along with four other Jews fleeing Nazi genocidal tyranny, lived in a claustrophobic attic in Amsterdam’s Jordaan district during the Nazi occupation, “trapped like caged creatures,” as Sullivan empathetically describes their ordeal.

They went into hiding in July 1942, but were discovered in August 1944. They spent a total of 761 days undetected in the secret annex at 263 Prinsengracht, during which time Anne composed her remarkable diary, which was published posthumously following World War II.

As Sullivan writes in the preface, Anne’s betrayal has been an unsolved mystery, or a secret well kept, until now. It was cracked open by a “Cold Case Team” of researchers and investigators.

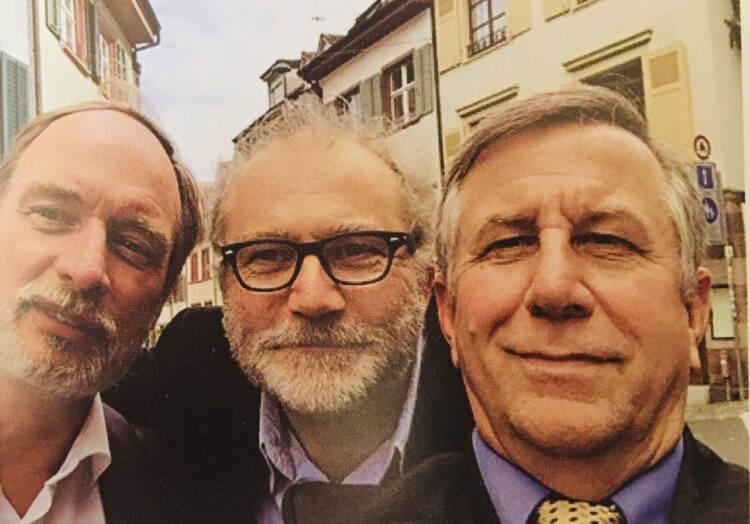

In 2016, the Dutch filmmaker Thijs Bayens invited his friend, the journalist Pieter van Twisk, to investigate the Nazi raid that led to the discovery of the annex. Scores of investigators, including Vince Pankoke, an American who had been a special FBI agent for 27 years, devoted five years to the project.

They were bent on achieving two overlapping goals — identifying the betrayer and trying to understand what happens to a captive population under the boot of a harsh enemy occupier. Sullivan’s instructive book deals not only with these pertinent issues, but with Holland’s Jewish community before, during and after the Holocaust.

For decades after the war, Holland clung to the rosy narrative that most Dutch people had opposed the Nazi occupation and supported or had joined the resistance movement. The reality was “much less monochromatic,” she notes, saying that “a more nuanced picture” has emerged in the past 30 years. This balanced interpretation of Dutch history is reflected in her book.

Sullivan acknowledges that Holland, from the 17th century onward, acquired an image of tolerance due to its status as a safe haven for persecuted Jews. And compared to other European countries, antisemitism in Holland was relatively mild. Yet Holland was home to a Nazi movement, and three-quarters of Dutch Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, the highest death rate in Western Europe.

Of 140,000 Jews, 107,000 were deported and only 5,000 returned from German extermination camps. Twenty five thousand Dutch Jews went into hiding, but one-third were betrayed, like Anne, her sister Margot, her parents, Otto and Edith, and several of their acquaintances.

Otto Frank, Anne’s father, was a German Jew. Born in Frankfurt in 1889, he served in the German army during World War I. In recognition of his bravery, he was promoted to lieutenant. Everything changed after the Nazi seizure of power in 1933. Seven months after Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor, Otto and his family emigrated.

They settled in Amsterdam, where they felt at home. Otto earned a living from two companies he had established thanks to a loan from his brother-in-law. Opekta was a retailer of pectin, the gelling agent in jam. Pectacon sold herbs, spices and other seasonings.

He hoped that Germany would respect Holland’s neutrality, as it had during World War I. But on May 10, 1940, Germany invaded Holland. Within five days, the Dutch government surrendered. From that point inward, Holland was ruled by a German official, Arthur Seyss-Inquart.

In December 1940, seven months after the German invasion, Otto moved his business into a 17th century building at 263 Prinsengracht facing one of the city’s ubiquitous canals. Like many of the period buildings, it had a four-storey annex attached at the rear, says Sullivan. Although the annex was invisible from the front of the building, it could be seen from the back, which abutted on a large interior courtyard. Sullivan speculates that Otto rented this building because he had been thinking of going into hiding.

Prior to moving into the new premises, Otto subverted an antisemitic German law by “aryanizing” his company. He did this by appointing one of his employees, Victor Kugler, as managing director. “Had the company remained Jewish, it would have been liquidated,” says Sullivan.

In January 1941, Jews were required to register with the authorities. The vast majority complied with this order, knowing that failure to do so carried a prison sentence of up to five years. By then, the Dutch Nazi Party (NSB) had been reconstituted after having been banned in 1935. NSB gangs roamed the streets, assaulting Jews and smashing Jewish properties.

Amsterdam’s Jewish quarter was sealed by the Germans and Dutch police on February 12, 1941. Ten days later, 389 Jews were sent to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

On February 25, some 300,000 Dutch workers staged a massive strike to protest the roundups. According to Sullivan, it was the first public protest against the Nazis in occupied Europe and the only mass demonstration against the deportation of Jews to be organized by Christians. The organizers were arrested and executed.

During this period, Otto desperately tried to obtain foreign visas for himself and his family. Otto’s quest coincided with the mass deportation of Dutch Jews to Nazi extermination camps in Poland by way of the Westerbork camp in Holland.

The Nazi-appointed Jewish Council played a central role in this process. Its chairmen were David Cohen, an academic, and Abraham Asscher, the director of a diamond factory. In retrospect, the council was “a weapon in the hands of the Nazis,” Sullivan writes. “It had had hardly any influence and delayed nothing.”

Sullivan believes that more than 10,000 Jews, including those in mixed marriages, managed to receive exemptions from the deportations.

Otto and his family retreated into the annex on July 6, 1942. They were assisted by one of his employees, Miep Gies, and her husband. The Franks were joined by Hermann van Pels — who had worked for Otto since 1938 as an expert in spices — and his wife, Auguste, and son, Peter. Another person who found refuge there was the dentist Fritz Pfeffer.

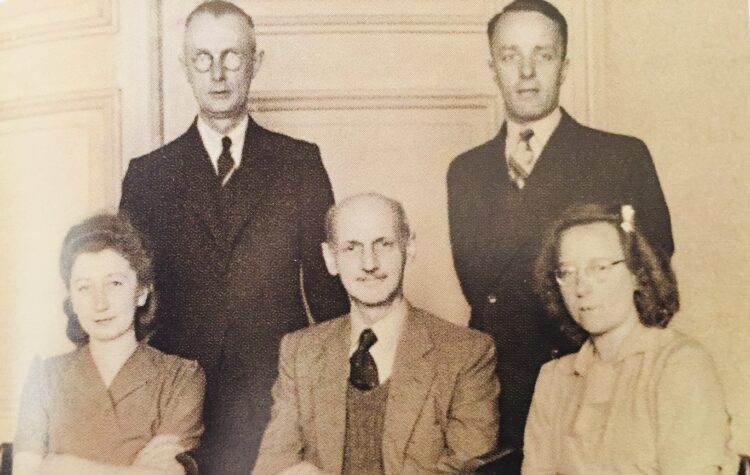

During their incarceration in the annex, they were completely at the mercy of Otto’s employees, who remained loyal and provided them with the necessities of life. Among them were Johannes Kleiman and Bep Voskuijl.

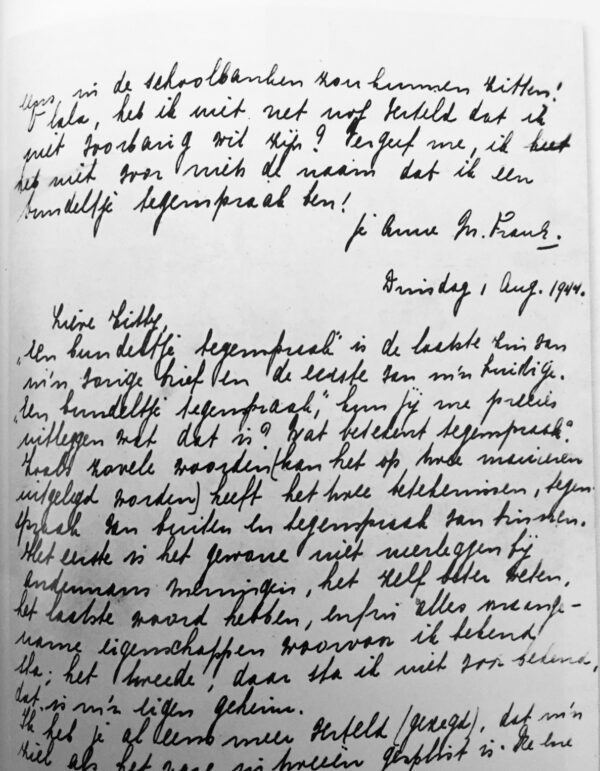

Anne started her diary shortly after she received it as a gift for her 13th birthday on June 12, 1942. She wrote continuously. Her last entry was on August 1, 1944, three days before she and her companions in the attic were arrested by a 33-year-old German SS officer, Karl Josef Silberbauer, who was attached to a “Jew-hunting” unit. He was accompanied by two Dutch policemen and a detective. Silberbauer’s commanding officer, Julius Dettmann, had received a telephone tip alerting him to hidden Jews in a warehouse complex.

Anne and her family were caught when the tide of the war had turned against Germany. Two months earlier, the Allies had captured Rome and landed on the beaches of Normandy in the largest amphibious invasion in history. And the month before, the Red Army had moved into Poland and German army officers attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

When Silberbauer ordered Anne and the others to collect their belongings for the trip to Gestapo headquarters, she picked up her father’s briefcase, inside of which was her diary. Silberbauer grabbed it from Anne, threw the diary on the floor, and filled the briefcase with valuables and money that Otto and the others had accumulated for an emergency.

“Had Anne held on to the briefcase and been allowed to keep it …. her diary would certainly have been taken from her … and destroyed or lost forever,” says Sullivan.

After being detained for four days, the eight prisoners were transported to Westerbork, which had been opened in 1939 to accommodate legal and illegal Jewish refugees from Germany and other countries where Jews were imperilled.

A Holocaust survivor who met Anne there said she was animated by a sense of freedom. This was an illusion, of course. From Westerbork, she was sent straight to Auschwitz. And from there, she and her sister were transported to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where they perished in 1945. Their mother, Edith, died of hunger in the same year. Otto, the only survivor, was liberated by the Red Army on January 27, 1945. He died in 1980.

Dutch Jewish survivors who returned to Holland were treated shabbily, says Sullivan. They were denied public assistance and instructed to apply to Jewish organizations for financial help. Still other Jews received tax bills covering the years they had been imprisoned in Nazi camps.

Toward the close of 1945, Otto decided to publish Anne’s diary, which had been saved by Gies. “He knew that Anne wanted it published, and he was determined to show the world that something positive could come out of all the grief,” writes Sullivan. The first edition came out in 1947. American and British editions followed in 1952. Since then, 30 million copies of The Diary Of A Young Girl have been published around the world.

Dutch police investigations into Anne’s betrayal were conducted in 1947-1948 and 1963-1964, but no firm conclusions were drawn. In 2017, Anne Frank House in Amsterdam theorized that the Germans found Anne by chance during a search for illegal weapons and goods. Gies hinted she knew the name of the betrayer, but never disclosed it.

Cold Case researchers studying the profiles of possible betrayers considered several individuals. Among them were Tonny Ahlers, who had been a member of the Dutch Nazi Party, and Anna van Dijk, a Jewish blackmailer and Nazi informant. There was no hard-and-fast evidence that the betrayer had been a resident of the working-class Jordaan district.

Having eliminated them as persons of interest, the researchers focused their attention on Arnold van den Bergh, a prominent notary and member of the Jewish Council. “The Cold Case team knew that (he) and his wife were never deported, were never listed as being in any concentration camp, and survived the war,” Sullivan observes. “What did Van den Bergh do to secure their survival?”

After the war, the Jewish community set up “honor courts” to question Jews who had collaborated with the Germans. Having been on the Jewish Council, Van den Bergh and four other defendants were summoned to appear before one of these courts in Amsterdam. They chose not to participate. In 1948, the court ruled that they had assisted the Nazis in a variety of ways. Van den Bergh, who died in 1950, was tacitly cleared of having betrayed Anne.

The Cold Case researchers, however, are of the view that Van den Bergh was, in fact, the person who betrayed Anne. “He did not turn over the information out of wickedness for for self-enrichment, as so many others had,” says Sullivan. “His goal was simple: to save his family. That he succeeded while Otto Frank failed is a terrible fact of history.”

Ultimately, Van den Bergh was not responsible for her death, she adds. “That responsibility rests forever with the Nazi occupiers who terrorized and decimated a society, turning neighbor against neighbor. It is they who were culpable in the deaths of Anne Frank, Edith Frank, Margot Frank, Hermann van Pels, Auguste van Pels, Peter van Pels, and Fritz Pfeffer. And millions of others, in hiding or not.”

Since the publication of The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation, the Dutch publisher, Ambo Anthos, has suspended further printing, though the American publisher intends to continue selling the book.

Ambo Anthos made this announcement after a group of Dutch historians blasted it as “a shaky house of cards” and claimed it “does not hold water.”

John Goldsmith, the president of the Anne Frank Fund, based in Basel, told a Swiss newspaper that the accusation against Van den Bergh could be likened to a “conspiracy theory” and is “full of errors.”

In response, the Cold Case team has defended its research as “very detailed and extremely solid” and insisted that Van den Bergh cannot be “removed as the main suspect.”