It was one of the strangest incidents in the annals of the Middle East.

Middle Eastern politics can often be murky, but the Saad Hariri comic opera was unprecedented in terms of its layered opaqueness.

Now, more than a month after the Lebanese prime minister tendered his resignation in Saudi Arabia, only to rescind it in Beirut some weeks later, pundits are still scratching their heads over this bizarre and unprecedented incident.

While its broad outlines seem clear, virtually everything else about is shrouded in mystery.

On November 3, Hariri — a dual citizen of Lebanon and Saudi Arabia — was summoned to Riyadh, the Saudi capital, by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the 32-year-old son of King Salman and the heir apparent to the Saudi throne.

Speaking on Saudi television, Hariri — a Sunni Muslim — resigned. Claiming his life was in danger, he condemned Iran, Saudi Arabia’s rival, and its Lebanese ally and proxy, Hezbollah. “Wherever Iran is present it plants discord and destruction, attested to by its interference in Arab countries,” he said. “Iran’s hands in the region will be cut off.”

These uncompromisingly tough words were music to the ears of Saudi Arabia — the seat of Islam in the Muslim world — and Israel.

Saudi Arabia, a predominately Sunni Muslim nation, and Iran, the foremost Shiite power in the region, have been squaring off for dominance in the Middle East since the Iranian revolution in 1979. Tensions reached a breaking point last year, when Saudi Arabia severed diplomatic relations with Iran after Iranian demonstrators attacked the Saudi embassy in Tehran following Saudi Arabia’s execution of a prominent Shiite cleric.

Saudi Arabia, like Israel, denounced the 2015 nuclear agreement, which was signed by Iran and six major posters — the United States, Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany. The Saudis fear that the accord, while freezing Iran’s nuclear program for at least the next decade, will enable Iran to become a full-fledged nuclear power.

Much to the disgust of Iran, which has repeatedly called for Israel’s destruction, Saudi Arabia has established a behind-the-scenes security relationship with Israel based on the Arab proverb that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” On December 10, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said that Iran is ready to restore relations with Saudi Arabia if its ends its “false friendship” with Israel.

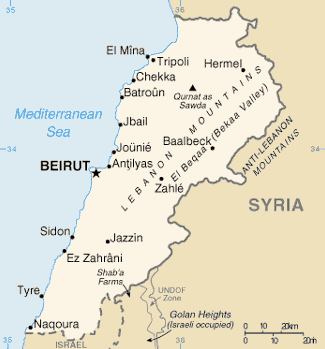

Saudi Arabia’s struggle with Iran has played out primarily in Syria, Yemen and Lebanon.

In Syria, Iran supports the secular regime of President Bashar al-Assad, while Saudi Arabia backs rebels fighting to topple Assad. In Yemen, Iran supports Houthi fighters challenging the central government of President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who has fled into exile. Saudi Arabia has pushed back by means of an air campaign supported by the United States. And in Lebanon, Iran exerts increasing influence through Hezbollah, which is arguably the most powerful political and military organization in the country and which fought a month-long war with Israel in 2006.

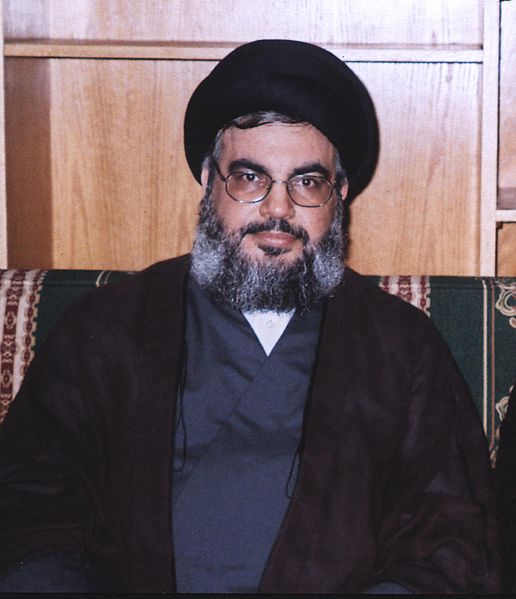

Last year, after two-and-a-half -years of political deadlock, Hariri resumed his position as prime minister of Lebanon, a country riven by deep sectarian tensions. Hezbollah, headed by Hassan Nasrallah, acquired 16 of the 30 seats in Hariri’s cabinet. Hezbollah thus became the chief power broker in Lebanon, which was dragged into the Arab-Israeli conflict by the Palestinians after the 1967 Six Day War and by Hezbollah in the wake of Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon.

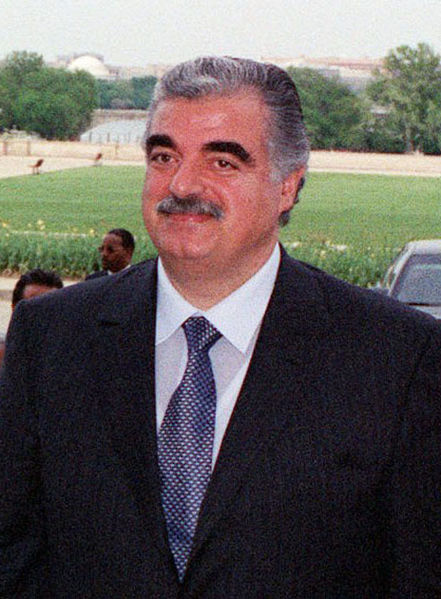

Hariri, the head of the Future Movement, agreed to work with Hezbollah despite its involvement in his father’s violent death. A wealthy businessman and the former prime minister, Rafik Hariri was assassinated in 2005 in Beirut. According to a United Nations tribunal in The Hague, Hezbollah had a direct hand in his assassination. Syria, the arbiter in Lebanese politics until its decision to withdraw its garrison from Lebanon in the same year, also played a role in his murder.

Hariri may well have been thinking of these events when he announced he was stepping down. Within hours of his speech, the Houthis in Yemen fired a missile at the airport in Riyadh. The Saudis shot it down, but blamed Iran and Hezbollah for the launch, characterized it as an act of war and ordered its citizens to leave Lebanon.

Reacting to Saudi Arabia’s accusation, Nasrallah heightened tensions by claiming the Saudis had asked Israel to attack Lebanon.

Amidst the sound and fury, Saudi Arabia arrested a bevy of princes, government ministers and businessmen on charges of corruption, prompting speculation that Prince Salman was consolidating his grip on the ruling House of Saud hierarchy.

As this drama unfolded, rumors abounded that Saudi Arabia had pressured Hariri to resign so as to check Iranian and Hezbollah influence in Lebanon, and that Hariri would not be released from house arrest until his Hezbollah-leaning government had fallen.

Saudi Arabia’s ploy came to nothing when Lebanese President Michel Aoun, an ally of Hezbollah, said he would accept Hariri’s resignation only in person.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia came under intense Lebanese and international pressure to allow Hariri to return to Lebanon. As the foreign minister of Lebanon, Gebran Bassil, visited Western capitals in a bid to free Hariri, French President Emanuel Macron invited Hariri and his family to Paris. Leaving Saudi Arabia after two weeks, Hariri paid Macron a visit. En route to Beirut, he paused in Cairo to confer with Egyptian President Abdul Fatah al-Sisi to discuss “the stability of Lebanon.”

Having returned home, Hariri rescinded his resignation, dealing a setback to Saudi plans to roll back Iranian and Hezbollah influence in Lebanon.

The issue, however, remains relevant.

In accordance with Hariri’s views, the Lebanese government has since reaffirmed its policy of “disassociation” from regional conflicts. It was adopted four years ago to keep Lebanon out of the civil war in Syria. Lebanon has managed to insulate itself from that six-year-old war, but 1.5 million Syrian refugee have poured into Lebanon, seriously straining its resources, and Hezbollah has sent thousands of troops to defend Assad’s regime.

Hezbollah, having grown stronger since its bold intervention in Syria, could place Lebanon at risk if it confronts Israel militarily again. Keenly aware of this possibility, Hariri and his allies have called on Hezbollah’s to disarm. Hezbollah has categorically rejected this demand, thereby leaving Lebanon open to widespread carnage should another Israel-Hezbollah war break out.

Last week, Hariri redoubled his efforts to insulate Lebanon from a future war. Following the visit of an Iranian-backed Iraqi militia leader to the Lebanese border with Israel, a trip that was arranged by Hezbollah, Hariri accused him of having violated Lebanese laws and instructed Lebanese security forces to ensure that such “military activities” do not happen again.

It’s doubtful whether Hariri’s edict will be respected, since Hezbollah is virtually free to do whatever its pleases in Lebanon, Crown Price Mohammed bin Salman notwithstanding.