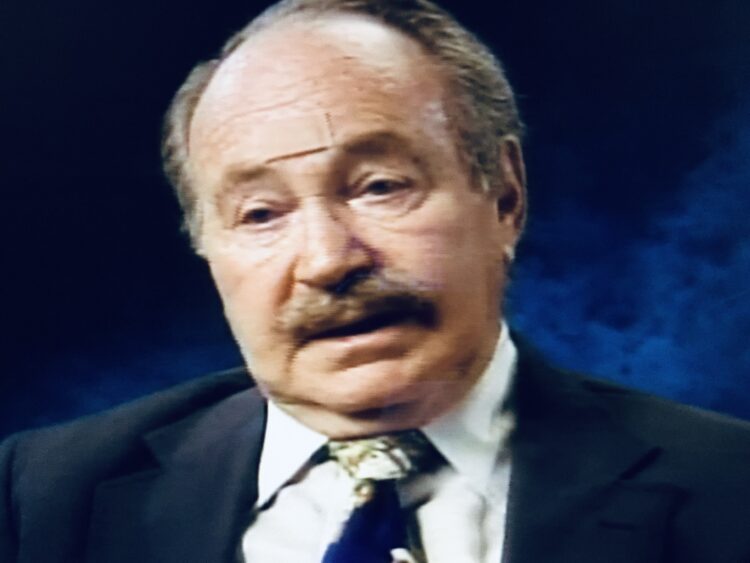

He was, as an admirer succinctly put it, a “bolt of lightning.”

Marty Glickman was probably the fastest Jewish sprinter of all time. A member of the U.S. track and field team at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, he was later the first Jewish broadcaster in major league sports.

He’s the subject of James Freedman’s absorbing documentary, Glickman, which can be viewed on ChaiFlicks, the Jewish streaming network.

“I always ran,” he says in the first moments of the film. “It was just my nature to run.”

“I was always the fastest kid on the block,” he adds, speculating he inherited his athletic prowess from his father, an immigrant from Romania.

Thanks to his abilities, he received a sport scholarship from Syracuse University, where he played on the football squad and competed for the track team.

At the Olympic trials, he finished fifth in the sprints, just behind the great Jesse Owens, and qualified for a place on the U.S. track team. Glickman’s best time would be 9.5 seconds.

Although some Jewish athletes boycotted the Olympics in Nazi Germany, Glickman wanted to go there to break the myth of Aryan invincibility. He and sprinter Sam Stoller would be the only Jews on the American team.

Glickman and Stoller were due to compete in the 400 meter relay race, along with Foy Draper and Frank Wykoff. At the last moment, coach Dean Cromwell replaced them with Owens and Ralph Metcalfe, claiming their replacements would enhance the chances of a U.S. victory.

Cromwell’s decision was highly irregular. He would not budge from his position even when Owens volunteered to step aside so that Glickman could be included in the race.

The Americans won the gold medal by a wide margin. The Germans finished a distant fourth. Glickman was angry, frustrated and disappointed, having missed the chance of a lifetime for Olympic glory.

Some believe that Cromwell was motivated by antisemitism. Still others think that Avery Brundage, the head of the U.S. Olympic team, removed Glickman to appease the antisemitic Nazi regime. This may well have been true, though Brundage heatedly denied the accusation. After the Olympics, tellingly enough, Brundage’s construction company won the bid to build the new German embassy in Washington, D.C.

Glickman’s days as a world-class sprinter essentially ended in the wake of the Olympics. In 1937, he segued into sports broadcasting. Except for a brief period, when he served with the Marine Corps in the Pacific theater, he spent the rest of his career in broadcasting.

Unlike Mel Allen, whose real surname was Israel, Glickman did not anglicize his name. Which, perhaps, is why one of his employers, NBC, fired him when he was at the top of his game.

Glickman hit his peak in the 1950s and 1960s, when he was a play-by-play announcer at football, basketball and baseball games and at horse races. He covered the New York Giants, the New York Jets and the The New York Knicks.

As a broadcaster for 56 years, he covered 200 track meets, 1,000-plus basketball games, 3,000-plus baseball games and 15,000 horse races. In addition, he offered commentary at high school football games of the week. And for a decade, he was the voice of Paramount newsreels.

In the estimation of his peers, Glickman changed the landscape of sports broadcasting, and this film pays him proper homage.