My eldest daughter called with the news around bedtime on April 2. The Canadian Jewish News, the weekly newspaper of record where I worked as a reporter, editorial writer and columnist from 1974 until 2013, was ceasing all operations with the publication of the April 9 edition.

My first reaction was one of surprise and shock. How was it possible that Canada’s leading English-language Jewish periodical, serving communities in Toronto and Montreal but also beyond, could not sustain itself in such a prosperous country?

I had assumed that the CJN was on a fairly firm financial footing after a near-death experience in the spring of 2013, when I was laid off in an abrupt, ruthless cost-cutting operation, along with a few reporters, the editor, the general manager, and the advertising manager.

My optimism was misplaced. Newspapers and magazines by the hundreds have fallen in recent years as digital platforms have replaced them. In this turbulent and uncertain climate, the CJN, buffeted by declining advertising revenues, an aging readership and declining community subsidies, could barely keep its head above the water.

And when the coronavirus pandemic struck, resulting in the mass closure of businesses, the end could not be far off. As the CJN’s publisher, Elizabeth Wolfe, wrote in a lament, “Unfortunately, we too have become a victim of COVID-19. Already struggling, we are not able to sustain the enterprise in an environment of almost complete economic shut down. It is with deep sadness that we announce the closure of our beloved CJN, both in print and online.”

In her missive, Wolfe, the daughter of previous publisher Ray Wolfe, held out the hope that the CJN can be revived yet again. Revival may be possible once we’ve seen the back of this catastrophic health and economic crisis. But for the moment, the CJN is dead and gone, having been felled by forces way beyond its control. One can only hope that this vacuum in Canadian Jewish journalism will eventually be filled.

Even during the best of times, one could never be sure what the future held in store for the CJN. Paid circulation was never more than 31,000 in a 300,000-strong Canadian Jewish community. The majority of its readers were middle-aged and older, and most young people did not bother with it, regardless of the caliber of its articles, all of which conformed to professional industry standards and a few of which, in terms of style and content, rose to superior heights.

Certainly, it did not attract the interest or attention of the intellectual and academic class.

Part of the problem was that the CJN, in my time at least, discouraged explicit criticism of Israel’s often blinkered approach to the Palestinians and a two-state solution. The CJN’s misguided policy, I strongly suspect, turned off some potential readers and created the impression that it was a mere adjunct of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Occasionally, my stories and columns were edited to reflect the CJN’s status quo position on Israel and the Arab-Israeli conflict, a topic in which I specialized and which, to my satisfaction, provided me with opportunities to report from the Middle East. In the interests of keeping my job, I sometimes practised a form of self-censorship, knowing full well where the boundaries lay.

To some readers, my views merited dismissal. Meyer Nurenberger, the right-wing Zionist who founded the CJN in 1960 and who edited a short-lived competitive Jewish newspaper in the 1980s, went as far as to accuse me of being a Palestinian dupe. Years later, I was advised to treat Palestinian Authority President Yasser Arafat, whom I interviewed in 1994 in the Gaza Strip, with greater severity.

Periodic calls for my dismissal went unheeded because each of the four editors with whom I worked harmoniously — Ralph Hyman, Maurice Lucow, Patricia Rucker and Mordecai Ben-Dat — defended me from detractors, some of whom were ideological, inflexible and unreasonable. I’m eternally grateful for their support and their instinctive understanding that journalism is a respectable craft, and that journalists should be given the freedom and the space to explore ideas.

In one instance, though, my critics were absolutely right, objecting to a photograph of myself at a restaurant consuming a non-kosher meal of a smoked meat sandwich and a vanilla milk shake.

I’m glad to say that, with very few exceptions, I enjoyed my 38-year run at the CJN. In fact, I regarded my job with the enthusiasm one brings to a favorite hobby.

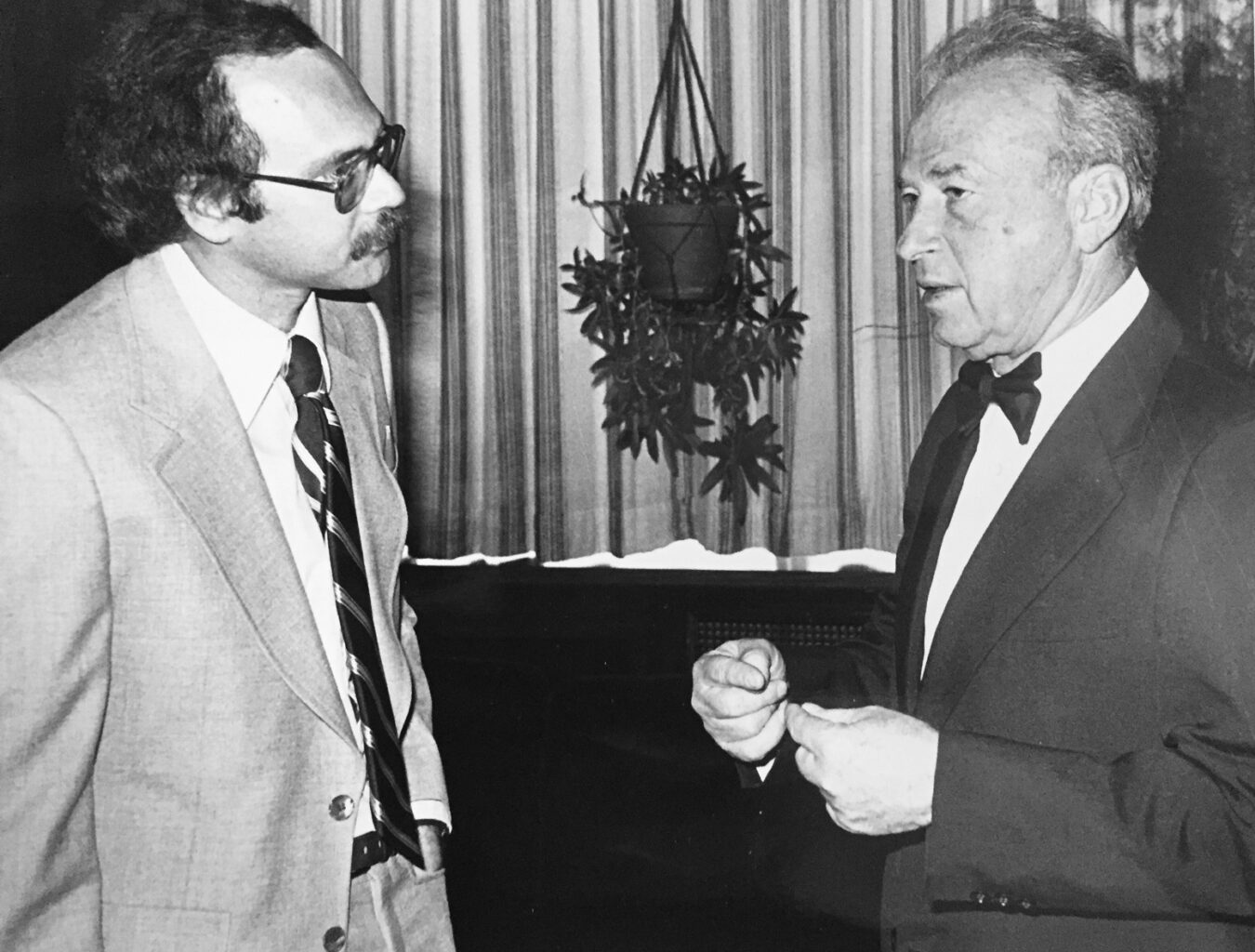

I wrote local news stories, produced analyses of Israeli and Middle East politics, turned in pieces on the Holocaust, churned out book and movie reviews and contributed travel pieces. In the process, I interviewed many people, including Yitzhak Rabin and Chaim Herzog, respectively Israel’s prime minister and president. I was a jack-of-all-trades and revelled in my role. My late father, a practical man, once expressed concern that I would be unable to earn a living in journalism, but fortunately the CJN proved him wrong.

I was hired by Ralph Hyman, a courtly old school journalist whose tenure as editor began after his retirement as an esteemed reporter for The Globe and Mail. He had a nose for a good story and recognized that my idea of a series on Syria, Israel’s arch enemy, Egypt, Israel’s newest “friend,” and Jordan, which shared the longest border with Israel, would go over well with our readers.

His successor, Maurice Lucow, was the former editor of a garment trade magazine. Gruff and friendly depending on his mood, he introduced computers to our office, though he never personally used one and preferred to edit paper versions of incoming stories. Lucow, who retired to Victoria after stepping down in the late 1980s, handed me assignments that required me to travel to, among other destinations, Argentina, South Africa, Venezuela and Costa Rica.

Lucow was succeeded by our first and so far only female editor, Patricia Rucker, who expanded our staff and gave me considerable leeway in travelling to countries such as Russia, Poland, Germany and Ukraine. By chance, I was fortuitously in Moscow when an abortive coup shook Russia to its core.

Mordecai Ben-Dat, a lawyer by training and a writer by inclination, took over from Rucker in the mid-1990s and stayed for 19 years, the CJN’s longest serving editor and the winner of a succession of awards for his incisive editorials. During his first years, the paper improved and grew fat and fairly prosperous. These, perhaps, were its golden years, when the possibilities seemed limitless. Although his center/right views on the Arab-Israeli conflict did not always coincide with mine, he tolerated dissent, much to his credit.

Over the years, freelancers flowed in and out of the office, but the most remarkable one by far was the columnist J.B. Salsberg. A communist until he broke ranks with the Soviet Union in the mid-1950s over its mistreatment of its Jewish minority, Salsberg was also a former member of the Ontario legislature as well as an ardent Yiddishist. Chatty, theatrical and irrepressible, he was a real character, cutting an imposing figure as he arrived each week to hand deliver his “col-yum.”

Although reporters came and went, as at any other newspaper, a few of us were “lifers” who liked their jobs and enjoyed the pace, the stability and the family atmosphere. But it all came to a crashing end, for some of us, when the CJN suddenly closed, only to reopen a couple of months later with a new editor, whom I never met.

Now, with the second closure of the CJN in seven years, he and the rest of his team find themselves in the wilderness of the unemployment line. I hope that they can get back on their feet once the current crisis subsides or ends, and that a new and financially secure Jewish weekly will emerge from the ashes.

Canada’s Jewish community would be all the poorer without such a newspaper.