The Geneva-based International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), one of the oldest humanitarian organizations, emerged from World War II with its reputation stained and damaged. Having come under fire for its failure to condemn the Holocaust or extend substantial assistance to Jews trapped in Nazi-occupied Europe, it attempted to improve its tarnished image by launching new aid initiatives in the aftermath of the war.

Gerald Steinacher’s first-rate book, Humanitarians at War: The Red Cross in the Shadow of the Holocaust (Oxford University Press), examines these issues in minute detail.

Steinacher, an associate professor of history and the Hymen Rosenberg Professor of Judaic Studies at the University of Nebraska, frames his work around the three men who shaped ICRC policy from 1928 to 1955.

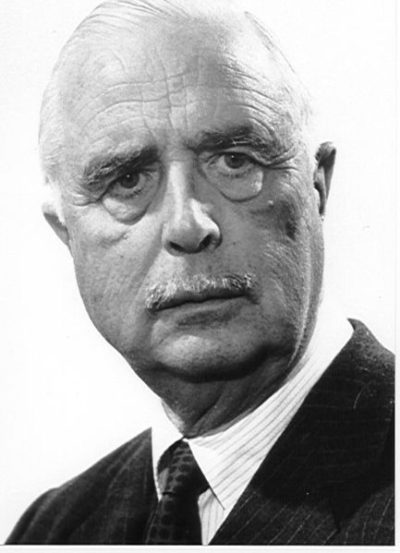

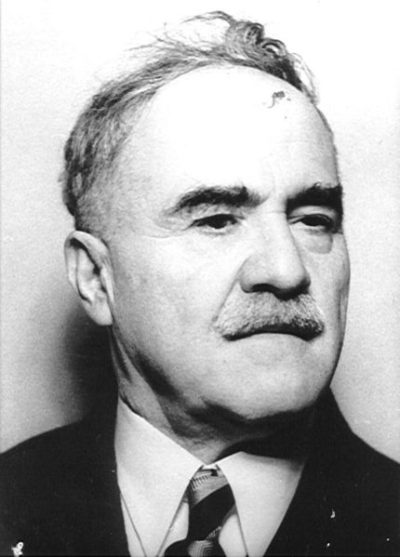

Max Huber was its president from 1928 to 1944. Due to his ill health, his chief assistant and successor, Carl Jacob Burckhardt took charge of the ICRC in the autumn of 1942. Paul Ruegger, who succeeded Burckhardt in 1948, had been Switzerland’s ambassador to fascist Italy.

For all intents and purposes, Burckhardt probably exerted the greatest influence on its policy toward Jews during the period under discussion. Although he considered Adolf Hitler a parvenu, he regarded Germany as an important bulwark against communism. “Burckhardt was no great admirer of Hitler, but no particular friend of the Jews either,” writes Steinacher. In a private letter to a friend in 1933, Burckhardt wrote that “there is a certain aspect of Judaism that a healthy Volk has to fight.” And in an early draft of his memoirs, he held Jews responsible for the outbreak of the war.

Steinacher suggests that the Swiss government’s cautious approach to Jewish refugees from Germany influenced the ICRC.

Switzerland, fearful of a German invasion, admitted about 30,000 Jewish refugees during the course of the war, but rejected at least as many. Jews were granted only temporary asylum and had to leave as soon as possible. The costs of maintaining them was borne by the 18,000-strong Swiss Jewish community.

Until 1938, German citizens entering the country required no visa. But worried that it might be swamped by “foreign elements,” Switzerland asked Germany to mark the passports of non-Aryans with a red J stamp. On the eve of the war, the German Red Cross repeatedly told the ICRC not to interfere on behalf of German Jews because such requests would be ignored.

Although Switzerland was neutral during the war, groups of doctors and nurses from the Swiss army were sent to the Eastern front in 1941 and 1942 in support of Germany, and 755 Swiss nationals enrolled voluntarily in the Waffen SS. Switzerland, too, traded with Germany and was a key market for art looted from Jewish collectors by the Nazis.

In 1942, in the wake of the Wannsee conference in Berlin, Burckhardt learned of Nazi plans to systematically murder the Jews of Europe. His informant was Gerhart Rieger, the World Jewish Congress representative in Switzerland. Burckhardt, in turn, passed the information on to the U.S. consul in Geneva. Shortly afterward, the United States and nine of its allies publicly denounced Germany’s plan and warned the perpetrators they would be held responsible.

Knowledge about Nazi atrocities did not translate into action on behalf of imperilled European Jews. Leery of antagonizing Germany, the Swiss government persuaded the ICRC to remain silent with respect to Germany’s maltreatment of Jews. In any event, Burckhardt preferred quiet diplomacy to public protests. It was only in the 1990s that the ICRC admitted that its silence constituted a “moral defeat.”

With the tide turning against Germany after 1942, the ICRC yielded to Jewish pressure inside and outside Switzerland and embarked on a two-pronged strategy to help Jews and non-Jews threatened by Germany. The ICRC began intervening on behalf of civilian concentration camp prisoners. It also started sending food parcels to camps such as Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Ravensbruck and Buchenwald.

A little later, it sent food parcels to ghettos in Poland and to the Theresienstadt camp in Czechoslovakia. In June 1943, the ICRC proposed that parcels should be sent to Auschwitz, but its proposal was rejected by the German Red Cross.

Steinacher contends that the establishment of the War Refugee Board by the United States in 1944 was a turning point for ICRC’s rescue efforts. ICRC distributed food in Romania and Romanian-occupied territories and tried to protect Jews.

The ICRC, however, did not distinguish itself in an inspection tour of Theresienstadt. In preparation for the visit, the Nazis sanitized the camp, deported the sick and planted flowers. Once there, the Swiss delegates were shown a school, attended a soccer game and treated to a performance of a children’s theater play. The deception was a success, judging by the ICRC’s favorable report. The report, Steinacher says, “discredited the (ICRC) as being either naive or complicit in a cruel fiction.”

Emboldened by its propaganda coup, the Nazis produced The Fuhrer Gives a City to the Jews, an archly cynical documentary that portrayed the camp as a “spa town” where elderly German and Austrian Jews could live out their lives in peace. In fact, most of the inmates who appeared in the film were deported and murdered in Auschwitz.

The ICRC soon dispatched a delegation to Budapest, where it handed out letters of protection to Jews and placed Jewish hospitals, clinics, hotels and soup kitchens under its protection. Bowing to the wishes of the majority on the ICRC, Huber wrote a letter to Hungarian leader Miklos Horthy in June 1944 asking him to stop the deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. Huber’s intervention came too late. By that point, 400,000 Jews had already been killed.

Steinacher suggests that ICRC’s actions were, in part, impelled by its competition with the Swedish Red Cross, which had played a role in the rescue of Danish Jews in October 1943. This rivalry turned into a personal competition between Burckhardt and the vice-president of the Swedish Red Cross, Count Folke Bernadotte, a nephew of Sweden’s king who had expressed criticism of the ICRC. Burckhardt was thus involved in the ransom negotiations, initiated by SS chieftain Henrich Himmler, that enabled 1,684 Hungarian Jews to find a safe haven in Switzerland.

“For Burckhardt, helping the Jews ultimately became a way to please the Allies, especially Washington, as they moved forward toward victory,” writes Steinacher. “It had become clear to him that only a striking humanitarian ‘success,’ even one carried out in the waning days of the war, would quiet some of the criticism that had been increasingly directed against the ICRC and Switzerland.”

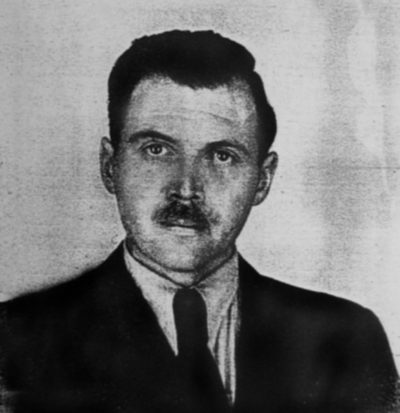

In the wake of the war, the ICRC tried to make amends by extending assistance to distressed civilians. In one of its first initiatives, it issued travel papers to displaced ethnic Germans. But much to ICRC’s embarrassment, thousands of Nazi collaborators and SS men, including perpetrators like Adolf Eichmann and Josef Mengele, availed themselves of these documents. Nine thousand Ukrainians who had been members of a Waffen SS division also used these documents to immigrate to Canada.

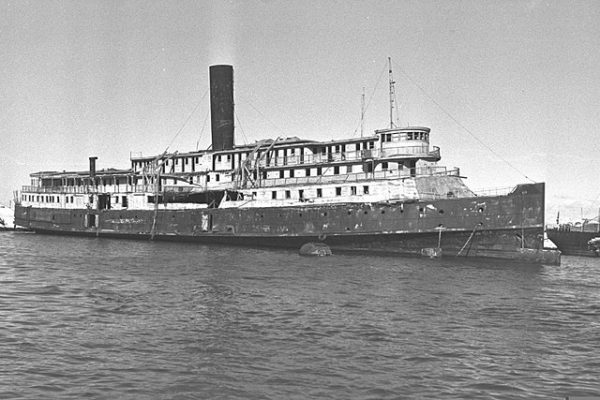

Torn by a sense of guilt over its tepid response to the Holocaust, the ICRC assigned three doctors to SS Exodus 47, which was carrying Holocaust survivors to Palestine. During the first Arab-Israeli war, the ICRC provided humanitarian assistance to Jews and Arabs, and Ruegger personally managed rescue efforts in war-torn Jerusalem.

In conclusion, Steinacher says the ICRC only became more active in aiding Jews once it was clear that Germany was going to lose the war. “But the practical aid the (ICRC) offered was very limited and marked by hesitation,” he notes. “The ICRC could have intervened earlier and with more determination, as the example of neutral Sweden shows.”

He adds that, with the drafting and signing of the new Geneva Convention in 1949, the ICRC overcame its checkered past and remained “a relevant, innovative and active force in shaping international law and humanitarianism.”