What was life like for a Jewish businessman in Adolf Hitler’s Germany? Hella Rottenberg and Sandra Rottenberg provide the answer in their intriguing book, The Cigar Factory of Isay Rottenberg: The Hidden History Of A Jewish Entrepreneur in Nazi Germany, published by Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

The man they have chosen to profile is none other than their late grandfather, Isay Rottenberg, a Polish Jew who bought a bankrupt cigar factory in Dobeln, a town in eastern Germany, five months before Hitler’s appointment as chancellor.

Rottenberg, described by his granddaughters as a combative and reckless person oblivious to danger, persisted with his enterprise, even as the toxic Nazi regime sharpened its poisonous antisemitic policies.

Small and stocky, with a shiny bald head, a prominent nose and large ears, he purchased the plant from Salomon Krenter, a Russian Jew, and renamed it Deutsche Zigarren-Werke. It was Germany’s first fully machine-operated cigar factory and it employed up to 1,000 workers.

He registered the company on October 4, 1932, when the two biggest factions in Dobeln’s municipal council were the Social Democrats and the National Socialists, which respectively held twelve and eight seats.

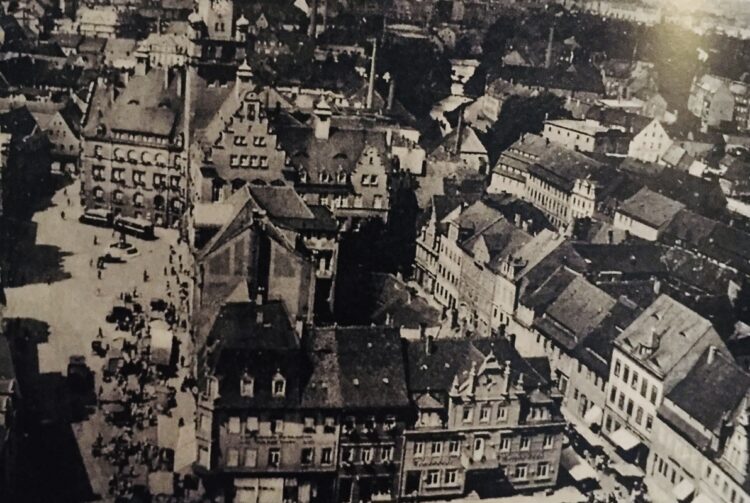

Debeln, located near the city of Dresden, is in Saxony. Eighty years ago, Saxony was the most heavily-populated, urbanized and industrialized state in the country. Although it was a redoubt of the labor movement and of socialist parties, the Nazis had a substantial following there.

During the Reichstag election of July 31, 1932, the National Socialists won 41 percent of the vote. Their chief representative in Saxony, Martin Mutschmann, was a fanatical antisemite. Rottenberg arrived in Debeln in August 1932, two weeks before the Nazis became the largest party in parliament.

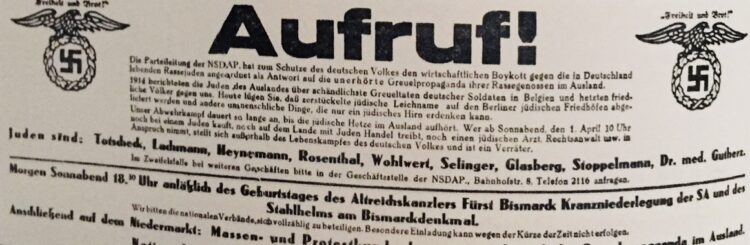

By the authors’ estimate, 29 Jews lived in Debeln around that time. The majority, originally from Eastern Europe, were newcomers to Germany. No sooner had Hitler assumed power than Julius Streicher, the publisher of the rabidly antisemitic newspaper Der Sturmer, demanded the removal of its Jewish residents.

Rottenberg, born in 1889 in the town of Iwaniska, was raised in Lodz, the center of the Polish textile industry. He learned the cigar business from his father, a dealer. Rottenberg moved to Berlin prior to World War I and held successive jobs as a button and cigarette paper salesman.

In 1910, he visited Amsterdam, where his uncle on his mother’s side, Abraham Ptasznik, lived. There he met Lena, his wife-to-be. During this period, he and his Dutch cousin, Jos, became business partners. Rottenberg prospered, but the stock market crash of 1929 virtually ruined him.

When he turned up in Debeln, ten cigar factories were already in operation, compared to 32 in 1894. In all of Germany, there were more than 5,000 cigar makers. Of these, 3,000 were one-man operations.

Fearing they would be destroyed by mechanization, the owners of these small factories lobbied to keep the hand-rolled method of production in place. Their guild convinced the government to impose a ban on cigar-making machines. This edict, signed by Hitler and the minister of economy and finance, went into effect on July 15, 1933.

“The aim of the ban was to slow down the modernization of the cigar industry, the chief target being the only fully automatic cigar factory in Germany: the Deutsche Zigarren-Werke,” write the Rottenbergs.

Rottenberg reacted to the ban by dashing off a letter to the minister in charge of economic affairs and enlisting the support of Dobeln’s mayor, Herbert Denecke, a member of the Nazi Party. Denecke proved to be an ally. “Until now, (Rottenberg) has acted with the utmost decency and has always endeavored to provide work and bread for his workforce,” he wrote in a glowing letter.

Nevertheless, Rottenberg found himself embroiled in problems after he was accused of having committed bankruptcy fraud flowing his takeover of the factory from Krenter. As a result, the company was expropriated by the Deutsche Bank, and Rottenberg had to surrender his Dutch passport before being detained.

The fate that befell him was not unusual. By 1935, one-quarter of the Jewish businesses in Germany had been Aryanized.

Rottenberg’s granddaughters believe he remained in Germany during this turbulent era because he was attached to German culture and was convinced that justice would prevail. He was eventually released thanks, in part, to the efforts of Johann Steenbergen, a Dutch diplomat stationed in Germany. But Rottenberg was expelled from Germany in May 1938, six months before the Kristallnacht pogroms.

Deutsche Bank sold Deutsche Zigarren-Werke to a competitor in 1937 for four times the price Rottenberg had paid just five years earlier.

Returning to Amsterdam, he left Nazi-occupied Holland in the summer of 1942. He and his family were admitted into Switzerland and lived there for the duration of the war.

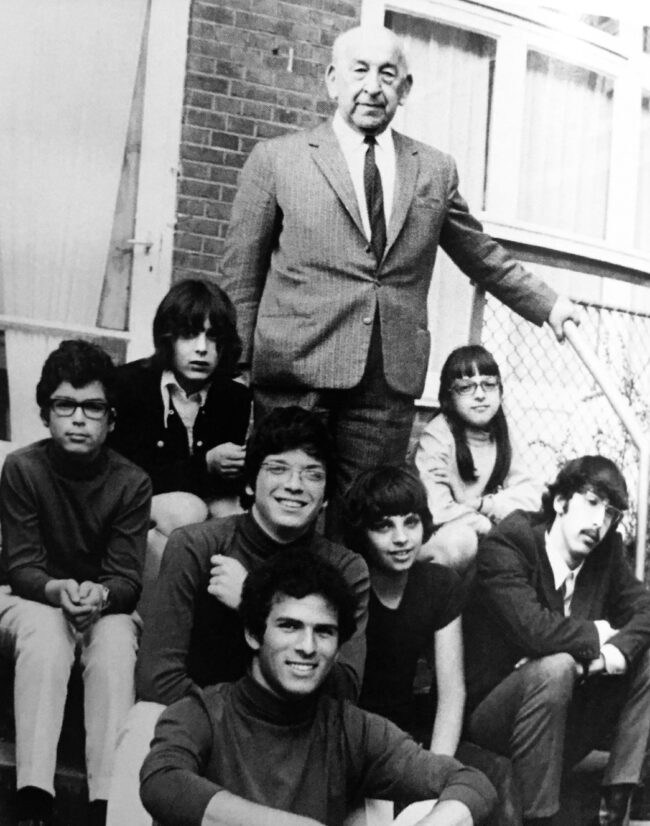

In postwar Amsterdam, Rottenberg was the director of J. Rottenberg & Sons, a manufacturer of plastic drinking straws and tubes. He died in 1971.

Deutsche Zigarren-Werke prospered during the war. In 1952, it was nationalized by East Germany. Cigar production stopped in 1981 when a candy factory bought the buildings.

Rottenberg’s granddaughters say he never discussed this facet of his life with them. As they put it, “Perhaps he realized, in retrospect, it had been a monumental mistake to buy and run a factory in Germany in 1932, and preferred not to be reminded of it. Besides, he never talked about his past anyway … He preferred to keep his emotions to himself. Look forward rather than back. Onward, and forget the rest.”