World War II was not just another destructive conflict between warring nations, but a nationalist crusade on the part of Germany to acquire territory, attain hegemony, disseminate Nazi ideology and murder Jews on a massive industrial scale.

When Germany attacked Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, touching off an international conflagration that dragged on for six years and claimed the lives of at least 60 million people, Adolf Hitler, the German fuhrer, was driven by two broad objectives: to redraw the map of Europe and wipe out an ancient people.

On the 74th anniversary of this catastrophic war, I have a special and abiding interest in it because it’s so profoundly personal. My parents were directly scarred by it, and I, in turn, was deeply affected by it.

My father, David, who was born and raised in Lodz, was a soldier in the Polish army. After being wounded on the battle front, he was dispatched to a clinic 0r hospital in Germany. Having recovered, he was sent back to Lodz, where he worked as a fireman in the Nazi ghetto, the last one to be liquidated.

Genya, my mother, was also a Polish Jew from Lodz. During the Nazi occupation, she toiled in a factory that produced goods for the German war effort. In August 1944, when the Germans began dismantling the ghetto, she, along with the last ragged inhabitants of the ghetto, including my father, was shoved into a cattle car on a train bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau, a Nazi extermination camp in Poland.

In this cruel, ghastly and surreal destination of the doomed, my mother learned, to her utter dismay, that the last drop of human kindness and decency had already been spilled. Her only child, a boy who played the violin and the brother I never knew, was wrested away from her, never to be seen again. His loss, so sudden and abrupt, haunted her for the rest of her life. Not a day passed without her thinking of him.

I don’t know, and never will know, how she and my father survived the purgatory of Auschwitz and the camps to which they were subsequently sent. Their coping skills must have been formidable. Or, perhaps, they were astonishingly lucky.

In postwar Canada, they rebuilt their lives, but the war-ravaged Poland of their youth, where the Holocaust unfolded, was imprinted on their minds and bodies in bold face. By a process of osmosis, I appropriated their traumas, and was ineluctably drawn into the terrible drama of World War II, which made the Holocaust possible.

This war has been the subject of an avalanche of commentaries and books, and now Antony Beevor, a British historian, has written a magisterial account of the most seminal single event of the 20th century. The Second World War (Little, Brown and Company), is comprehensive in scope, running to 863 pages with the index, and containing useful maps and graphic black-and-white photographs.

Beevor focuses on the land, sea and air war in Europe, which absorbed the brunt of the casualties, and devotes relatively little space to the Pacific theatre. In passing, he returns again and again to the Holocaust, which, in retrospect, was more than merely a footnote in a global struggle.

Aptly enough, Beevor, the author of such bestsellers as The Fall of Berlin 1945, Stalingrad and D-Day, launches The Second World War with a detailed account of Germany’s invasion of Poland. He suggests that the Polish army never had a chance. Against the German army’s almost three million troops, Poland was able to muster only about one-third of its 1.3 million force.

Having been warned by Britain and France that a premature call-up might give Germany a pretext to attack, Poland delayed the order for a general mobilization. Once the fighting had begun, Poland was handicapped by obsolete weaponry and a lack of radios. Poland’s fate was sealed on Sept. 17 when the Soviet Union, in accordance with a non-aggression pact signed with Germany the month before, invaded eastern Poland, thereby carving up the country into German and Soviet zones of occupation.

In a preview of things to come, German soldiers mistreated the Jewish population, cutting off the beards of Orthodox Jews and raping young women, in contravention of Germany’s 1936 Nuremberg Laws forbidding sexual contact between Aryans and Jews.

Although Germany rolled over Poland in less than a month, Berlin paid a heavy price for its victory. Eleven thousand German soldiers were killed and 33,000 were wounded, compared to the Polish death toll of 70,000 killed and 133,000 wounded. Germany lost 560 aircraft, a surprisingly high toll in light of Germany’s success in effectively knocking out the Polish air force on the first day of the war. The Red Army emerged relatively unscathed, losing 996 men.

Interestingly enough, as Beevor notes, Britain’s declaration of war shocked many Germans who believed that Germany could achieve victory in Poland without being sucked into a world war. The so-called Phoney War, which lasted for six months after Poland’s partition, created a false impression in Berlin that Germany might be able to reach an accommodation with Britain and its ally, France. Germany was also hopeful that the United States’ disinclination to intervene on behalf of the Allies would prompt Britain to sue for peace.

Germany’s invasion of the Low Countries and France in 1940 dashed hopes that the war could be resolved by peaceful means. The Battle of Britain, a pivotal moment in which Germany’s dream of conquering Britain was obliterated once and for all, hardened feelings on both sides. Beevor describes the Battle of Crete as “the greatest blow” suffered by the Wehrmacht since the beginning of the war.

Hitler justified the invasion of the Soviet Union by claiming that the defeat of “Jewish Bolshevism” would force Britain to come to terms with Germany. But in Beevor’s view, the primary objective of Operation Barbarossa was the seizure of Moscow’s oil fields and sources of food production, the attainment of which, in Nazi eyes, would render Germany invincible.

Incredibly enough, the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, refused to believe reports that a German invasion was imminent. The German ambassador in Moscow – an anti-Nazi who was later executed for his role in the 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler – personally delivered the most plausible warning of its kind. Stalin was skeptical. “Disinformation has now reached ambassadorial level,” he exclaimed.

Stalin was certainly no naif, yet he accepted at face value an assurance by Hitler that German troop movements eastward were designed to put German soldiers out of range of British bombing. According to Beevor, Stalin was more concerned by the supposed threat posed by the Baltic states. In the meantime, the Soviet Union continued to supply Germany with grain, precious metals such as chromium and manganese and more than two million tons of oil.

The Red Army was not completely prepared for Germany’s invasion in 1941. Seasoned officers had been executed in political purges. There were not a sufficient number of forward defence lines. And Soviet military aircraft were lined up in neat rows on tarmacs, presenting easy targets for the Luftwaffe. On the first day of the war, 1,800 Soviet bombers were destroyed, the majority on the ground. (Twenty six years later, in the opening round of the Six Day War, the Egyptian and Syrian air forces suffered a similar fate when bombed by Israeli jets in surgical strikes).

From the day German troops poured across the Soviet border, Jews were subjected to mass murder, notwithstanding a comment by the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, that genocide, “the Bolshevik method of physical extermination,” would be “un-German and impossible.”

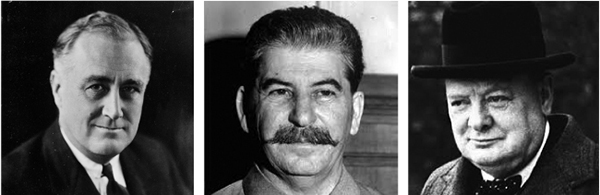

The refusal of Britain’s prime minister, Winston Churchill, to commit to an invasion of northwest Europe so as to take the pressure off Moscow aroused Stalin’s suspicion that Britain wanted the Soviet Union to bleed. But the decision by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt to ship huge consignments of food and sophisticated weaponry to Moscow, which saved the Soviet Union from famine and increased the mobility of the Red Army, defused Stalin’s suspicions. Nonetheless, as Beevor points out, Stalin declined to apprise the United States of intelligence data, compiled by Soviet spy Richard Sorge, of an impending Japanese air raid on the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawaii.

In a supreme act of folly, Hitler declared war on the United States four days after Pearl Harbor, assuming that the crisis in the Pacific would prevent Washington from playing a decisive role on the European fr0nt for two years. His calculation was misguided. America’s entry into the war, combined with Germany’s failure to capture Moscow, was a “geo-political turning point,” in Beevor’s assessment. As he puts it, “From that moment, Germany became incapable of winning the (war) outright, even though it still retained the power to inflict appalling damage and death.”

Apart from its capacity to cause untold misery among the civilian populace of Europe, Germany had the power to annihilate Jews. In the summer of 1941, Himmler received instructions from Hitler to proceed with the murder of European Jews.”The world war is here, the destruction of Jewry must be the inevitable consequence,” German Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary.

Another turning point was Germany’s crushing surrender in Stalingrad, where over 500,000 German soldiers were killed, wounded or captured. Goebbels, in a cynical display of spin, attempted to create an heroic myth that Germany’s Sixth Army had perished in a courageous final stand. But his ploy backfired, convincing many Germans that the war could not be won.

Beevor deals at some length with what is clearly an obvious moral issue today but which was not universally regarded as one during the war: whether or not the Allies should bomb Auschwitz.

Jewish and Polish leaders, having urged Allied leaders to bomb the railway lines leading to Auschwitz, were disappointed to learn that no such policy was under consideration. The Allies claimed that their bombing techniques were not accurate enough to do the job, but most importantly, they hewed to the argument that Nazi atrocities could best be addressed by delivering strategic blows to the enemy in an effort to shorten the war.

These rationales, though seemingly reasonable, were undercut by Allied operations. In August 1944, when the gas chambers and crematoriums of Auschwitz were “processing” the last Jews from the Lodz ghetto, among other places, Allied aircraft from bases in Italy were dropping bombs on a methanol plant in Monowitz, an Auschwitz sub-camp.

Beevor acknowledges that Luftwaffe raids, particularly in the Soviet Union, killed something like half a million civilians. But in his estimation, the Allied belief that the war could be won exclusively by terror bombing German cities, like Wurzburg and Dresden, was “utterly wrong-headed.”

Nor does he agree with the proposal, propounded by the U.S. secretary of the treasury, Henry Morgenthau, that postwar Germany should be split up and transformed into “a country primarily agricultural and pastoral in character.” Churchill, at first, opposed the plan, but later voiced support for it. His foreign minister, Anthony Eden, was a dissenter, persuasively arguing that a democratic Germany would be needed to contain the spectre of Soviet communism.

Beevor, though mainly concerned in his narrative with developments in Europe, does not neglect the war in the Pacific. From Pearl Harbor and China to Burma and Okinawa, he writes masterfully and concisely of the battles that determined the outcome of the war in Asia.

Whether he is dealing with Europe or Asia, his conclusion remains the same. As he somberly observes,”The Second World War, with its global ramifications, was the greatest man-made disaster in history.”

It would be fair to say that I concur with Beevor’s sober conclusion.