The caliphate is crumbling.

Islamic State’s much-vaunted state-building project in Iraq and Syria, which attracted regional and international support and tens of thousands of recruits from the far corners of the globe, is tottering and on the cusp of collapse.

Since July, Islamic State has lost two more cities in Iraq, the loss of which significantly undermines its ambition of creating a fundamentalist religious state in the Middle East.

Late last month, Tal Afar — the hometown of some of its leading figures — fell to the Iraqi army in less than 10 days.

Two months ago, the momentous battle for Mosul ended after nine months of intense fighting as Iraqi government forces and Shiia militias, backed by U.S. air power and Iran in an unlikely tacit alliance of convenience, wrested Iraq’s second largest city from the clutches of Islamic State.

Captured by Islamic State in a lightning campaign in June 2014, Mosul fell after the fiercest urban warfare since World War II. By the time Iraq declared victory, Mosul was in smouldering ruins, with roughly three-quarters of its buildings having been destroyed, its electrical grid shattered and much of its population displaced.

Prior to these defeats, Islamic State lost control of the cities of Falluja and Tikrit, among others. And now, its de facto capital in Syria, Raqqa, is under siege by Kurdish and Syrian Arab forces. Half the city has been recaptured and the remainder is expected to fall within a matter of months.

All told, Islamic State has lost about two-thirds of the territory it conquered three years ago. During this period, 60,000 of its fighters have been killed.

The next phase of the military operation to eradicate Islamic State is likely to begin toward the close of this year. The focus will be on driving it out of towns and villages it still holds in the Euphrates River Valley. The leader of Islamic State, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, is believed to be hiding there, an area that runs from Deir ez Zor in Syria to Rawah in Iraq.

The U.S. commander who heads the American-led force battling Islamic State, General Stephen Townsend, envisages “tough fights” ahead. Until now, indoctrinated Islamic State fighters have put up fierce resistance.

As these forces advance, the Syrian army, supported by Russia, Iran, Hezbollah and a variety of Shiite militias, are converging on Deir ez Zor in eastern Syria, near the border with Iraq. The United States and Russia have reportedly discussed the possibility of using the Euphrates River in Iraq as a dividing line between Syrian government and U.S.-backed forces.

Despite its territorial defeats, Islamic State is far from finished as a formidable force.

It is producing propaganda material on the internet in a bid to recruit new acolytes and encourage supporters and sympathizers to undertake terrorist attacks.

Having begun the process of reverting to its insurgent roots, it has launched suicide attacks in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Yemen, Egypt, Nigeria, Afghanistan and the Philippines and continued to launch attacks on soft civilian targets in Europe, the latest one of which occurred in Barcelona in August.

“As Islamic State comes under greater and greater pressure, they will devolve into a more insurgent-like method of operation,” said Townsend. “They’ll try to hide with the population. Their cells will get smaller. Instead of companies and platoons, they’ll go to squads and cells. They’ll disperse. They’ll be smaller. They’ll be more covert.”

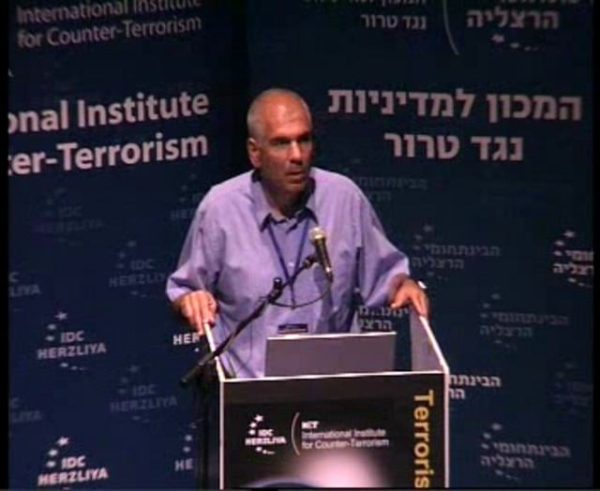

According to General Nitzan Nuriel, the former head of Israel’s Counter-Terrorism Bureau, the worst is yet to come.

“What we are witnessing is the death throes of the physical infrastructure of Islamic State in the region, and these will regrettably be accompanied by many incidents,” he warned recently. “I, for one, believe that a chemical attack is ahead of us.”

Islamic State, he noted, has the knowledge, the capabilities and the means to launch chemical attacks. Like a dying snake, Islamic State will lash out at its enemies furiously.