The trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel in 1961 was an historic event. For the first and only time, a major Nazi war criminal would face justice in the Jewish state. Recognizing its importance, the international media sent correspondents to cover it.

Israel considered the possibility of filming the trial for posterity, but there was one glitch. The presiding judges did not want cameras in the courtroom. They might be a distraction. How could this problem be fixed?

The Eichmann Show, a BBC feature film directed by Paul Andrew Williams and now available on Netflix, explores this dilemma in sober fashion.

It took the Mossad, Israel’s external intelligence service, 15 years to track down Eichmann. On May 11, 1960, he was finally caught. He was apprehended in a suburb of Buenos Aires, where he had been living under an assumed name for years, and was flown to Israel to stand trial for his complicity in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Jews.

An Israeli film company, headed by Holocaust survivor Milton Fruchtman, won the contract to film the four-month trial, which began on April 11, 1961. The Israeli government, headed by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, viewed the trial as an opportunity to exact vengeance and shine a light on the Holocaust for educational purposes.

Fruchtman hired Leo Hurwitz, an American who had been blacklisted by Hollywood due to his left-wing views, to direct the proposed film. Fruchtman (Martin Freeman) hired Hurwitz (Anthony LaPaglia) because he considered him the best in the business. That Hurwitz was a persona non grata in the American film industry was of no concern to him.

After arriving in Israel, Hurwitz discovered that the project hung in the balance. The judges who would sit in judgment of Eichmann feared that the presence of cameras would unsettle witnesses who would testify against him. A solution was finally found. The cameras would be placed in slits inside the wall of the courtroom, thereby satisfying everyone.

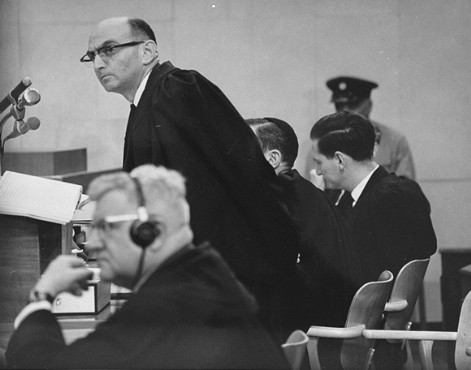

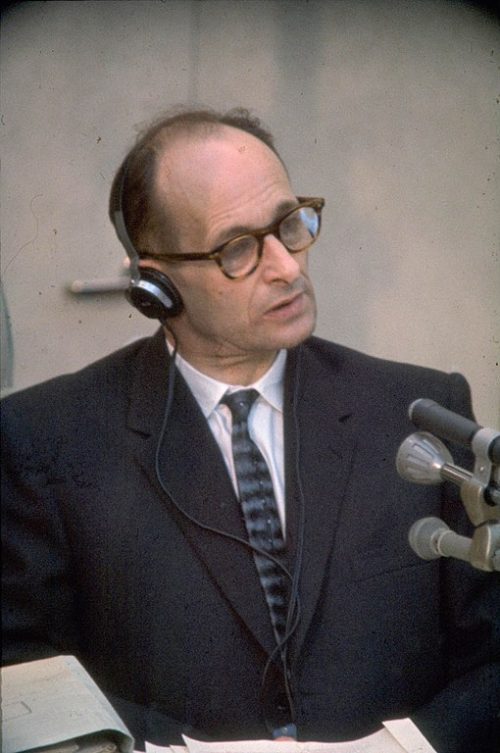

The Eichmann Show, which was originally broadcast on the 7oth anniversary of the Allied liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, uses actual file footage from the trial to create a sense of cinema verite. It’s a method that works exceedingly well because it endows the movie with a palpable sense of realism. The camera pans on Eichmann, sitting in a glass case surrounded by guards. Seconds later, an actor who portrays Eichmann magically appears on screen. Gideon Hausner, the prosecutor, is seen in a pensive pose. Within seconds, he’s replaced by an actor who bears a passing resemblance to him. And so on.

The film moves back and forth seamlessly between two poles: Fruchtman and his crew prepare for their important assignment, and the trial unfolds.

Clips of it were sent to 37 countries, but the audience dropped with the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and Yuri Gagarin’s flight into space. “Gagarin and the Bay of Pigs are killing us,” Fruchtman complains.

The trial, which is very big news in Israel, regains its mass appeal as a procession of Holocaust survivors deliver graphic testimonies about their horrific experiences. Eichmann looks on, a scowl or smirk on his face.

Footage of corpses, piled up on top of each other in the Bergen-Belsen camp, add to the mounting horror.

The historic significance of the trial is underscored when one of the characters, Mrs. Landau (Rebecca Front), a Holocaust survivor and the owner of the small hotel in Jerusalem where Hurwitz is staying during its duration, congratulates him on his work. Thanks to his film, she explains, the Holocaust has become a reality for Israelis who had belittled the stories of survivors like herself.

The Eichmann Show reaches a climactic moment when Eichmann admits he played a role in the Holocaust. Previously, he claimed he had not been involved in the extermination process at all.

Footage of Eichmann’s trial has been preserved for future generations, and this feature film pays homage to the band of men who made it possible.