Pandemics have shaped the world and Jews, in particular, have been victimized by them.

Jeremy Brown, the author of The Eleventh Plague: Jews and Pandemics from the Bible to Covid-19 (Oxford University Press), argues that pandemics, such as the bubonic plague and typhus, have impacted Jews profoundly. “It was a story of which I was completely unaware, despite being a physician and having a lifelong familiarity with Jewish sources,” he writes in his erudite and fascinating book.

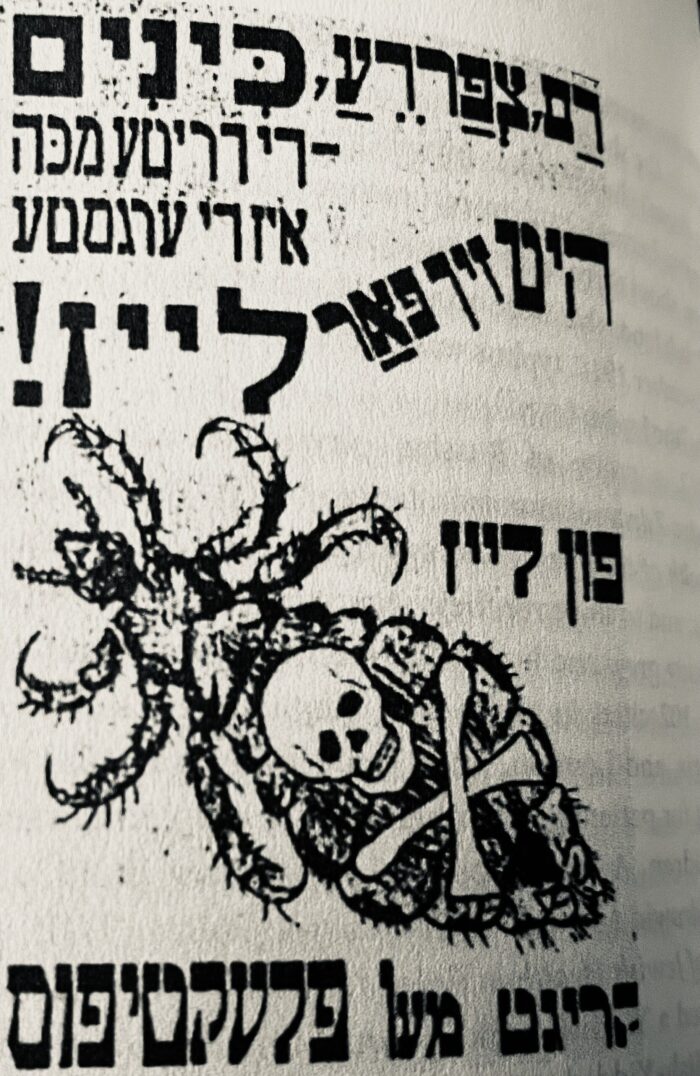

Of the countless plagues described in the Torah, the Ten Plagues are the most well known. As noted in the book of Exodus, these were blood, frogs, lice, fleas, pestilence, boils, hail, locusts, darkness and the death of a first-born child.

As he points out, there are scientific explanations for them.

The El Niño effect, a change in the weather over the eastern Pacific Ocean, heated the Mediterranean Sea and the atmosphere over Africa, causing the waters of the Nile River to warm up and red algae to form. This was the plague of blood.

When the Nile became uncomfortably warm for frogs, they fled to dry land, where they spread disease. The lice infestation occurred due to the rise in the population of small insects that thrived in unusually wet and humid conditions. Then came the fourth plague of larger fleas and biting flies, which, in turn, led to pestilence and the rest of the Ten Plagues.

The Black Death, which began in 1346 in a Crimean port, tore through Europe, North Africa and Asia, killing 75 million people, or 60 percent of the population. For Jews, the pandemic was not only a mortal threat, but a deadly force of antisemitic violence, the worst since the massacres of the Crusades.

Interestingly enough, the Black Death appears to have had a greater impact on Christians, says Brown, quoting the 19th century German historian Heinrich Graetz: “The Black Death took many Jewish lives, but it is estimated that their mortality rare was less than it was among Christians. Perhaps this was because they were more careful with their food and drink, or because they refrained from excess and gluttony, or because they were more particular about the mitzvah to visit the sick … They did all they could t0 prevent the sickness before it was untreatable…”

In the same vein, Rabbi Beryl Wein, an Orthodox Jewish historian, suggests that traditional Jews were more likely to survive the scourge due to halachically “regimented hand washing, care of the sick, and the immediate burial of the dead,” all of which served to control the Black Death.

Nonetheless, he adds, 2o percent of Europe’s Jewish population succumbed to the plague.

During the 18th century, tensions arose between “enlightened” Jews and pious Jews over epidemics and pandemics. While the former sought out knowledge about the nature of disease, the latter viewed them in moral and theological terms and were convinced they were divine punishment for sins.

“Sometimes, they took this position one step further and refused medical intervention altogether, preferring to rely on the chassidic leader to heal them,” writes Brown. “It should not come as any surprise that Jews have been blaming pandemics on their own moral and spiritual failings.”

More often than not, however, Jews were blamed for epidemics.

During a cholera outbreak in New York City in 1892, The New York Times held Russian and Hungarian Jewish immigrants responsible for it: “These people are offensive enough at best. Under the present circumstances, they are a menace to the health of the country … Cholera, it must be remembered, originates in the homes of this riff-raff.”

Conversely, when a vaccine was introduced to combat smallpox in 19th century Britain, antisemites claimed that it was nothing more than a devious plot by Jews to enrich themselves.

Centuries later, in Philadelphia, anti-vaccine beliefs were spread by a vocal Orthodox rabbi, Shmuel Kamenetsky, who dismissed vaccines as a “hoax” and “just a big business.”

The Nazis ascribed a typhus epidemic in Warsaw to Jews crammed into the Nazi ghetto. Jost Walblum, the chief health officer of the German occupation government in Poland, told a conference of physicians in 1941 that the mass murder of Jews was the only way of stopping repeated outbreaks of that disease.

Two years later, Hans Frank, the Nazi governor of occupied Poland, concluded that the extermination of Polish Jews was “unavoidable for reasons of public health.”

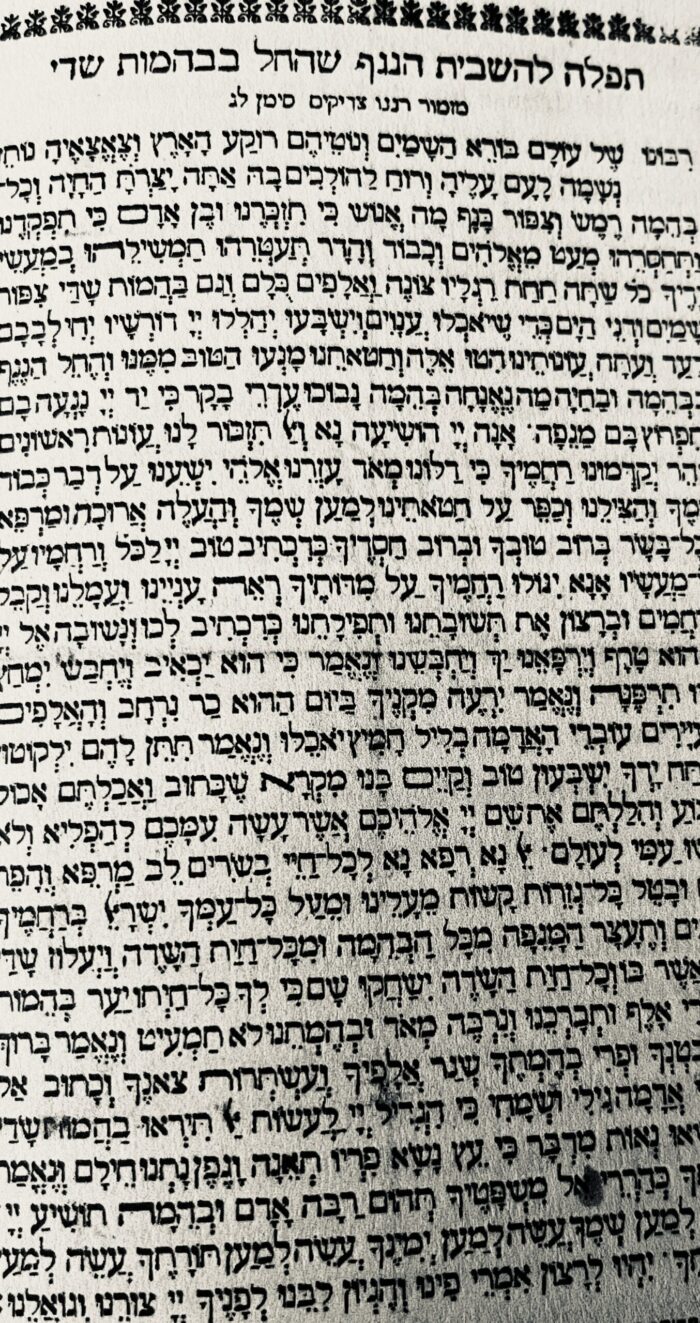

Impoverished Jews turned to amulets and folk medicine to ward off plagues simply because they could not afford the services of doctors. But even educated and well-off Christians had a high regard for amulets. Robert Boyle, the 17th century father of modern chemistry, believed that amulets of powdered toad cured urinary incontinence.

Shtetl Jews in the Russian empire resorted to “plague weddings” in cemeteries to ward off the ravages of disease. This custom may have crossed over from Christians. The Yiddish novelist Isaac Bashevis Singer mentions such weddings in Gimpel the Fool.

Jews also responded to epidemics and pandemics by fasting, a tradition that still exists. During Covid-19, Israel’s chief Ashkenazic rabbi, David Lau, declared a half-day fast to be observed the day before the Jewish month of Nissan.

Covid-19, in a sense, was a replay of earlier pandemics. As Brown writes, “Antisemites blamed the Jews for Covid-19, as they had blamed them for the Black Death and for scheming to get rich from the smallpox vaccine. But there can be no comparison between these modern canards, which while vile, remained rare, and the pogroms that followed the Black Death and affected nearly every community in medieval Europe.”

The conclusion to be drawn from pandemics is that Jews are often its inevitable victims.