In 1878, a master brewer in the eastern German city of Erfurt named Johann Andreas Topf founded Topf & Sons, a respectable company that would become the world’s leading manufacturer of malting equipment for the beer industry. Thirty six years later, Topf diversified its operations, introducing a line of crematorium furnaces.

The new product would have a devastating impact on European Jews.

Topf ‘s descent into the depths of evil began in the late 1930s, when the Nazi administers of Buchenwald — a concentration camp 20 kilometres from Erfurt — called upon its services.

Buchenwald, established in 1937, had a problem. How could it efficiently and safely dispose of the people who had succumbed to typhus?

Kurt Prufer, a Topf engineer born and bred in Erfurt, had the answer.

He had designed an incineration oven, bearing the stylized Topf logo, that met Buchenwald’s request in every respect. Buchenwald was impressed by Prufer’s solution and ordered Topf ovens. The contract saved Topf. The Depression, the global financial crisis of the 1930s, had nearly toppled Topf into insolvency.

By 1941, Topf and its chief competitor in Berlin, Heinrich Kori, which had participated in Germany’s euthanasia program, had installed ovens in a string of concentration camps — Dachau in Germany, Mauthausen in Austria (which had been annexed by Adolf Hitler in 1938) and Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland.

The ovens, fitted with sophisticated ventillation and exhaust systems, were the last word in technology, capable of burning a maximum of bodies quickly, using a minimum of fuel and leaving behind little or no physical evidence.

Apart from the ovens themselves, Topf developed the necessary accessories: the carts for loading corpses into the ovens and the fire hooks for moving body parts.

At its peak during World War II, this family business, run by the brothers Ludwig and Ernst-Wolfgang Topf, employed 1,150 workers and played a decisive role in the Holocaust.

Its cheerful motto was “Always willing to serve you.”

Topf’s complicity in genocide is chronicled in chilling detail and with German precision in The Engineers of the Final Solution: Topf & Sons, Builders of the Auschwitz Ovens, a museum and memorial that marked its third anniversary in January.

Opened to coincide with the 66th anniversary of the Red Army liberation of Auschwitz, it’s housed in Topf’s former administrative building, owned by a private investor today. A baleful indictment of the role German industry played in the extermination of millions of Jews, it attracts mainly student groups from Germany, Poland and Israel.

The tour begins in a dim staircase with a visual and written history of the Topfs, a seemingly normal German family, and proceeds to the upper floors. The joint office where Ludwig and Ernst-Wolfgang worked is closed to visitors, and all but two of the windows are papered over, but everything else in this drab building appears accessible to visitors.

The first window exposed to the outside offers a distant view of the clock tower in Buchenwald. The second window looks out to the railway line on which freight trains transported Topf equipment to concentration camps.

The brutally clinical exhibits in glass cases are fixed to the floor in spaces where engineers and draftsmen labored to refine the machinery of death ordered by the architects of the Holocaust.

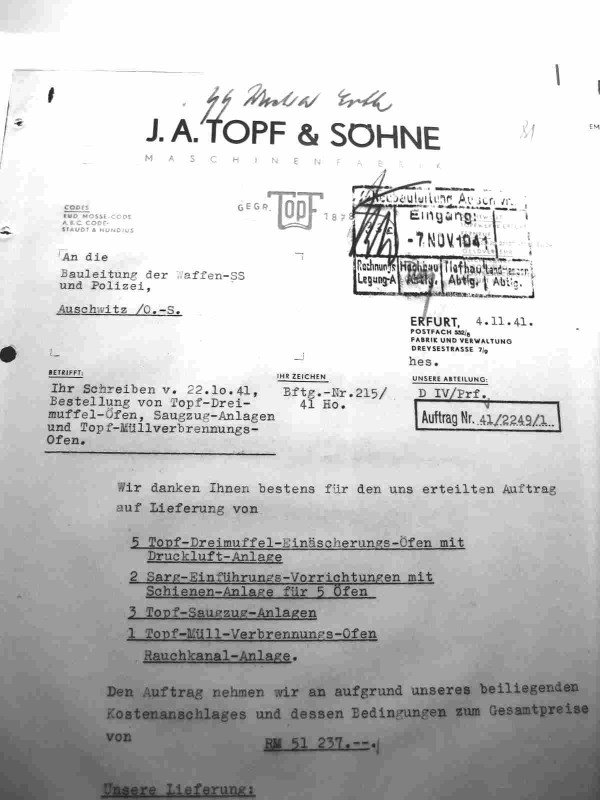

A correspondence between Topf and the SS, the Nazi organization that placed the order for ovens, is of particular interest. In a letter dated Aug. 19, 1942, an SS officer summarizes the discussions on the construction of four crematoria in Auschwitz. The language is precise, bureaucratic and bland, as if the topic had been, say, wooden cabinets.

In another letter, written on Jan. 29, 1943, Prufer assures SS chieftain Heinrich Himmler that “despite the scale of the construction and difficulties in conjunction with the weather conditions and the procurement of materials, work has proceeded apace.”

By that juncture, more than 500,000 Jews had been murdered in Auschwitz.

Prufer and the Topf brothers joined the Nazi party in 1933, when Hitler assumed power as chancellor.

By all accounts, the Topfs were neither fanatical Nazis nor rabid antisemites, merely hard-headed businessmen cashing in on an unprecedented opportunity. They employed, among others, communists and Germans of partial Jewish ancestry and apparently protected them from persecution and deportation.

Topf was not forced to work for the Nazis, fully understood what the ovens would be used for and was thus complicit in the implementation of the Holocaust.

As per the contract, Topf employees installed, tested and maintained the ovens and the ventillation and exhaust systems. Prufer visited Auschwitz at least several times. Under Russian interrogation in 1945, he admitted that “innocent humans beings had been “liquidated in Auschwitz gas chambers” and that their corpses had been “incinerated” in Topf ovens.

A perfectionist, he went to great lengths to please the SS. He and an assistant developed a four-storey “continuous-operation corpse incineration oven for mass use” that could have disposed of more bodies than was believed possible at the time. The project was approved of by the SS, but was never carried through to completion.

After the war, Prufer admitted his guilt and was imprisoned for 25 years. He died of a stroke in 1952.

The Topfs did not fare much better. Ludwig committed suicide after learning that the U.S. occupation army intended to investigate him. In a farewell letter, he wrote, “I was unfailingly decent, the opposite of a Nazi.”

Ernst-Wolfgang, who managed to avoid imprisonment, founded a company specializing in the manufacture of refuse incineration ovens. It went bankrupt. He died in 1979.

After the war, Topf reinvented itself as a manufacturer of equipment for the food industry, but shortly afterwards, the firm was expropriated by the new communist order in East Germany.

By the late 1980s, Topf’s administrative building, having fallen into disrepair, had been occupied by squatters. “It was just in ruins,” recalled Rebekka Schubert, a museum employee.

In 2003, a developer bought the site, which had been declared a landmark of historical significance, and renovated it.

Contemplating the contribution the museum can make in educating a new generation, Schubert said, “My hope is that young people will recognize that everyone has a choice of choosing good over evil.”