The Nazi machinery of mass murder is on stark and clinical display at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. The Evidence Room, a chilling and ghostly exhibition of white plaster components of the Auschwitz-Birkenau gas chambers, examines the central role that architecture played in the construction of this extermination camp in Poland.

The Evidence Room, which runs until January 28, 2018, features reconstructions of three key objects — a gas column, a gas-tight door and a gas-tight hatch — in the research work of Dutch-born Canadian architectural historian Robert Jan van Pelt, whose family was directly touched by the Holocaust.

Van Pelt, who teaches at the University of Waterloo and the University of Toronto, was an expert witness at the trial of British Holocaust denier David Irving in London 17 years ago. The trial took place after Irving accused American historian Deborah Lipstadt, a specialist in the Holocaust, of libel. Lipstadt won the case, saying, “History has had its day in court and scored a crushing victory.”

Two years after the trial, the subject of a recent feature film titled Denial, Van Pelt’s book, The Case for Auschwitz: Evidence from the Irving Trial, was published. It became a source of a new and emerging discipline, architectural forensics, which encompasses architecture, history, technology, law and human rights, and it was the inspiration of The Evidence Room.

Alejandro Aravena, the curator of the Venice Architecture Biennale, commissioned Van Pelt to create an exhibit about Auschwitz. Van Pelt and his colleagues, Donald McKay and Anne Bordeleau, designed The Evidence Room, which had its debut at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition in 2016.

The Evidence Room contains more than 60 plaster casts of architectural blueprints, architects’ correspondence, contractors’ bills, photographs and drawings.

Plaster was used to recreate the horrific landscape of Auschwitz because it is useful in the preservation of evidence. Poured as a liquid, it reveals every detail and brings back the past, nullifying all attempts to rewrite and whitewash history, as Holocaust deniers are wont to do.

Unfolding in two well-lit and austere rooms, it traces the work of German architects from 1941 to 1943 who won the contract to design a facility in Auschwitz to murder Jews and other “undesirables” on an industrial scale.

The first and most striking exhibit is a model of a crematorium, which burned the corpses of victims who had been asphyxiated in the gas chamber by poisonous cyanide pellets. The ovens, manufactured in Germany by Toph & Sons, could could dispose of 2,000 people within 15 minutes.

They were first herded into a basement cellar. Then, in an undressing room, they were forced to shed their clothes and give up their belongings. After guards ushered them into the gas chamber, the gas-tight door was locked. It was designed to swing outward so that it would open with corpses crushed against it.

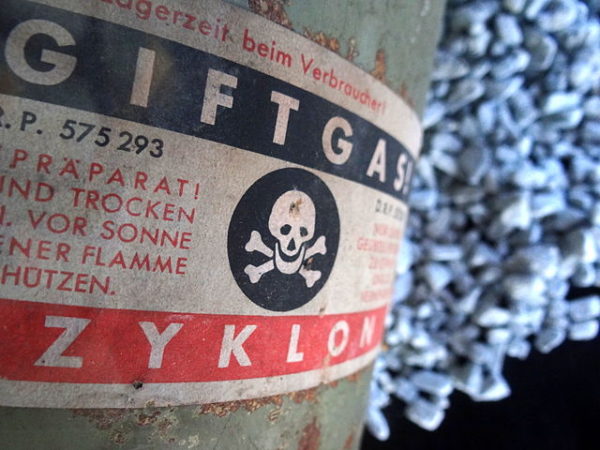

Zyklon-B pellets were lowered through the roof into mesh columns, killing the victims within minutes. Peep holes enabled guards to ascertain whether they had all died. The corpses, compressed together in a triangular shape, were moved to the crematorium. Fifteen ovens, working 24 hours a day, incinerated the bodies. The smoke passed into a high chimney, which was next to a coke and coal storage area and SS offices.

Auschwitz claimed the lives of 1.1 million people, mostly Jews, but also Roma, Red Army prisoners of war and Polish political dissidents who opposed Germany’s invasion and occupation of Poland.

Auschwitz became a searing symbol of genocide thanks, in part, to architects.

“Architecture can achieve good, even great things,” says Van Pelt, whose mother is a Holocaust servivor and whose uncle was murdered in Auschwitz. “Through the creation of public buildings and the articulation of public spaces it can teach us to live together. Yet architecture can also render harm.”

The Evidence Room, he adds, is compelling proof of “the unfathomable damage wreaked by the discipline when architects set out to design a factory of death.”