Joel and Ethan Coen have made an indelible impression, to say the very least. Since the release of their first feature film, Blood Simple, the Coens have carved out a niche for themselves in American cinema.

Their films, from Raising Arizona and Miller’s Crossing to Fargo and The Big Lebowski, are distinguished by memorable characters, laconic dialogue, creative cinematography, creepy atmosphere, quirky satire, dollops of surrealism and plenty of blood and gore.

The Coens do not appeal to everyone, but they have been nominated for 13 Academy Awards and have won four, two for screen writing, one for best director and one for best picture.

In honor of their contributions to the movie industry, the Toronto International Film Festival is running a retrospective about them at the TIFF Bell Lightbox. Joel and Ethan Coen: Tall Tales starts on Nov. 28 and ends on Dec. 20.

Two of their films, Blood Simple and Barton Fink, display the distinctive qualities that have made the Coens a household name.

Blood Simple, their first movie, was made on a shoestring budget with a cast of virtual unknowns. Shot in film noir style, Blood Simple rises above the ordinary by virtue of an intricate but compelling plot and inventive cinematography.

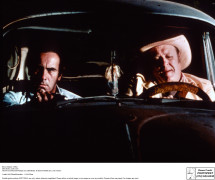

Two lovers, Ray (John Getz) and Abby (Frances McDormand), are driving on a Texas road at night as rain lashes the windshield. The lights of buildings are reflected on the glass, transforming it into something of a Jackson Pollack oil painting.

Abby’s husband, Julian (Ray Hedaya), the owner of a local bar, knows she is having an affair. Loren (E. Emmet Walsh), a private detective he has hired to provide the incontrovertible evidence, shows him graphic photographs of the pair making out in a roadside motel. Seeking vengeance, Julian offers Loren $10,000 to murder them.

The first thing you notice about the film, apart from the unconventional camera angles, are the people in it. They speak in a clipped kind of shorthand, never saying more than necessary. Abby and Ray exchange sentences rather than paragraphs. Julian, swarthy and glowering, practically spits out his words. Loren, a hardened cynic, takes it all in with a knowing laugh. He’s been there before.

The themes of betrayal and duplicity appear and reappear menacingly. What seems real turns out to be unreal. To the plaintive sound of country and Spanish music, passion and murder cross paths in an explosive mix.

The Coens create suspense in subtle brush strokes. Perspiration beads slide down Loren’s cheek in a palpable expression of nervousness. In a shower stall, a bubble forms, foreshadowing fear.

In Blood Simple, they construct a dark universe seething with malevolence.

Barton Fink, set in early 1940s Hollywood, is about profound disillusionment.

Fink (John Turturro), a successful Jewish playwright who has made his mark writing plays about the hopes and dreams of the “common man,” leaves New York City to become a contract writer for a movie studio in Los Angeles. He’s none too eager to go, but his manager convinces him that the big bucks he can earn there in a short period of time will enable him to devote himself, body and soul, to his art.

To the Coens, California is epitomized by the foaming waves of the Pacific Ocean crashing into a rock on the shore. To Fink, Los Angeles is symbolized by a painting of a young woman with long black air in a bathing suit sitting on a beach with her back to us.

The reality Fink faces in Hollywood is soul-crushing. The hotel room that has been reserved for him by Capitol Pictures is dim and seedy. The invigorating natural light of California is disturbingly absent.

His brash and talkative boss, studio mogul Jack Lipnick (Michael Lerner), wants him to write a “wrestling” film for one of his star actors. “Writing is king here,” he says in a blustery attempt to build up Fink’s confidence.

Lerner is uproariously brilliant in three scenes, first to dazzle and impress Fink, then to coddle him and, finally, to reprimand him.

From the outset, Fink is stymied by writer’s block. As he struggles to put words to paper, he meets a fellow scriptwriter, Mayhew (John Mahoney), who’s obviously modelled after the great southern novelist William Faulkner, who spent time in Hollywood. To his disappointment, Fink learns that Mayhew’s secretary/girlfriend (Judy Davis) is his ghost writer, at least in Tinsel Town.

Davis is impressive as Mayhew’s brittle yet shrewd mistress, and Mahoney’s portrayal of a besotted novelist-cum Hollywood hack is bang on. John Goodman, in the role of an insurance agent who befriends Fink, is just as fine.

In Blood Simple and Barton Fink, the Coens exhibit the skills that have served them eminently well and that have garnered them a devoted following.