On September 15, 1939, two weeks after Germany’s invasion of Poland, German troops occupied the small town of Kleczew, population 2,996, and proceeded to impose a reign of terror on its 746 Jewish inhabitants. Some two years later, they were systematically murdered in a nearby forest.

The Jewish community of Kleczew, as well as Jewish communities in the vicinity, were among the first ones on Polish soil to be eradicated by the Nazis. The methods of mass murder perfected there served as a model of future German operations against Polish Jews.

In short, the Holocaust began in earnest in Kleczew and environs.

The First To Be Destroyed: The Jewish Community of Kleczew And The Beginning Of The Final Solution (Academic Studies Press) examines this facet of the Holocaust in minute detail. Written by three Polish scholars — Anetta Glowacka-Penczynska, Tomasz Kawski and Witold Medykowski — and edited by Tuvia Horev, an Israeli healthcare specialist whose family lived in Kleczew for generations, it’s a thorough but repetitive work.

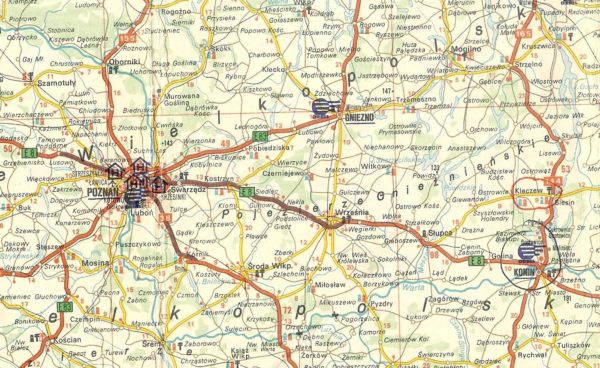

As far as is known, Kleczew, about 90 kilometres east of Poznan, was first settled by Jews in the early 16th century. During the 18th and 19th centuries, almost half of its residents were Jewish. On the eve of World War II, the percentage of Jews in Kleczew had dwindled to 25 percent of its population.

By 1935, 42 percent of Jews earned their income from trade. One-third were craftsmen. A few were professionals.

Kleczew and surrounding towns, incorporated into Germany in 1940 and governed by Arthur Greiser, were rapidly Germanized.

During the early phase of the occupation, the Polish intelligentsia and political opponents were singled out as the principal targets of German persecution and mass murder. The authors estimate that about 10,000 people were murdered by the Waffen-SS and the Einsatzgruppen, the mobile killing squads that accompanied the German army.

Almost immediately, Jews were placed in labor battalions and forced to level ground, dig trenches, clean streets, collect garbage and empty cesspools. In preparation for their invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Germans also assigned Jews to help build roads, bridges and viaducts. Over time, Jews were banned from most public places, and contacts between Jews and non-Jews were forbidden following the establishment of the ghetto.

The Jews of Kleczew were deported in the summer of 1940, expelled to Bełchatów, Bełchatów, Grodziec and Rzgów. Subsequently, males were sent to the Inowrocław labor camp. Still other Jews were murdered in forests near Kazimierz Biskupi.

The extermination of Jews in the Kleczew region shifted to Chelmno, 60 kilometres from Lodz, at the end of 1941. It was, the authors state, “the first permanent mass-murder facility” built during the Holocaust.

Corpses were buried in pits that had been dug by Jews and other inmates. Problems soon arose, as one witness wrote: “When it got hot, the corpses buried in the mass grave began to decompose. The earth moved. The air over a large area was poisoned. There were incidents of typhus. The Germans stopped receiving transports. Two crematorium furnaces were hastily constructed and they started burning the corpses. Mass graves were excavated and the Jews were ordered to incinerate the corpses in the crematoria.”

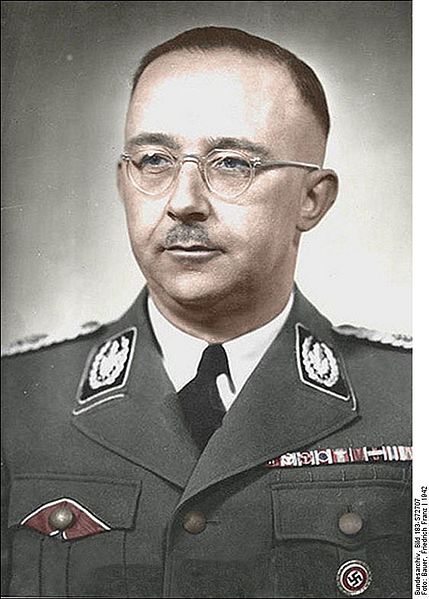

Senior Nazi officials, including Greiser and SS leader Heinrich Himmler, visited Chelmno. They were impressed by its efficiency. As Greiser observed, “People not only faithfully and bravely carried out all the tasks imposed on them … but additionally presented the best attitude.”

After the war, Greiser was extradited to Poland, and was hanged on July 21, 1946. Hans Bothmann, the second commandant of Chelmno, committed suicide while in British custody.

Very few Jews returned to Kleczew following the Holocaust. The ones who went back did not stay for long. The sole Jewish inhabitant who continued living there, Hannah Zakrzewska, was married to a Polish Catholic whom she had wed shortly after the outbreak of the war. She died in 1993, leaving Kleczew completely bereft of Jews.