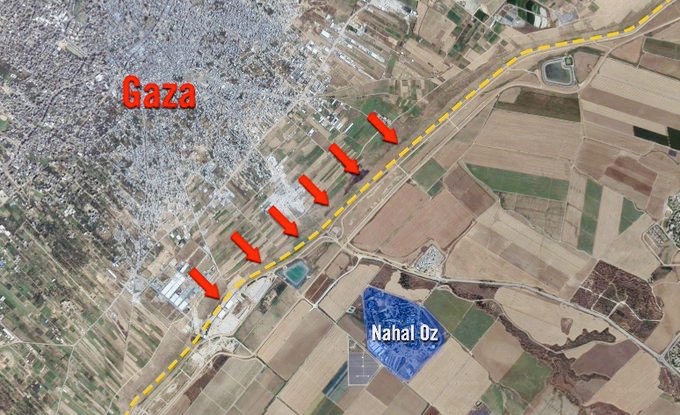

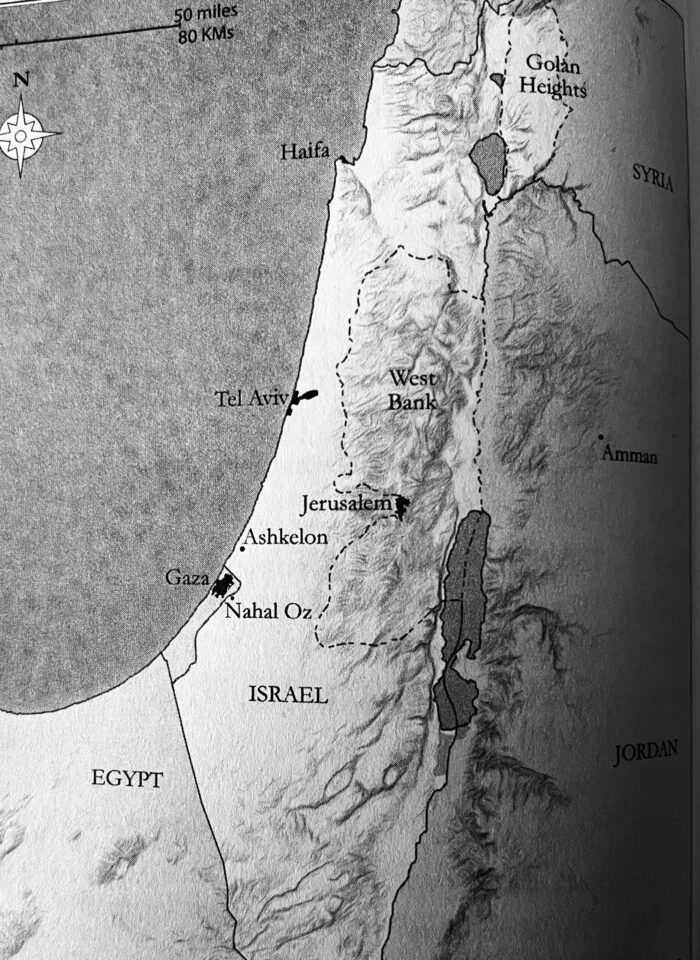

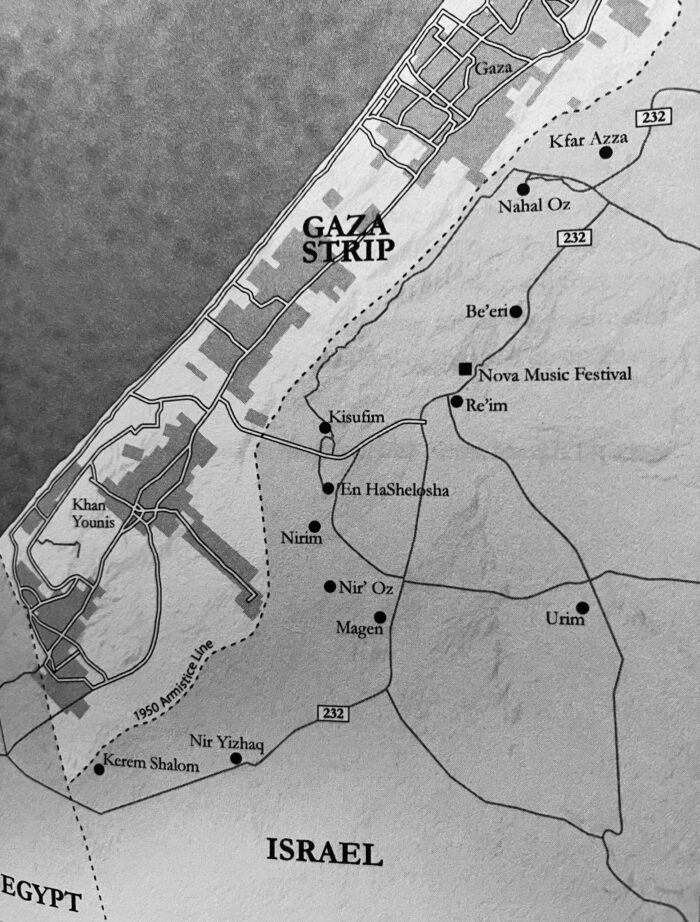

Kibbutz Nahal Oz, the Israeli community closest to the Gaza Strip, was attacked by Hamas terrorists early on the morning of October 7, 2023. It was not the first time it had been targeted, but this was the most devastating attack in its 70 years of existence.

Amir Tibon, his wife Miri and their two young daughters, Galia and Carmel, were among its 450 inhabitants who were awoken by the loud shrieks of mortars. In common with their neighbors, they sprinted into a reinforced safe room to wait out the barrage. Only later did they learn that Nahal Oz was among a constellation of kibbutzim, towns and army bases in southern Israel that had been ravaged by Hamas.

Prior to October 7, Nahal Oz, was one of the most bombarded places in Israel. And due to its close proximity to Gaza, it lacked the protection of the Iron Dome anti-missile system, whose interception hardware requires sufficient time to calculate the trajectory of an incoming projectile. That meant that a Nahal Oz resident had only seven seconds to find shelter before a mortar or rocket landed.

Tibon, the diplomatic correspondent of the daily newspaper Haaretz, knew all that, but he moved to Nahal Oz from Tel Aviv shortly after the 2014 Israel-Hamas war. On the eve of his arrival, a four-year-old boy from the kibbutz, Daniel Tregerman, was killed by a Hamas mortar, a tragedy that prompted 15 families, or one-quarter of its population, to leave for safer locales.

Tibon’s comprehensive account of October 7, The Gates of Gaza: A Story of Betrayal, Survival, and Hope in Israel’s Borderlands (Little, Brown and Company), focuses on that terrible day, but also delves into Nahal Oz’s history and examines Israel’s policy toward Hamas over the years.

While his narrative is often compelling, it unfolds in a somewhat disjointed manner. The uneven structure stems from his decision to intersperse his own experiences in Nahal Oz with that of political and military developments in Israel and Gaza.

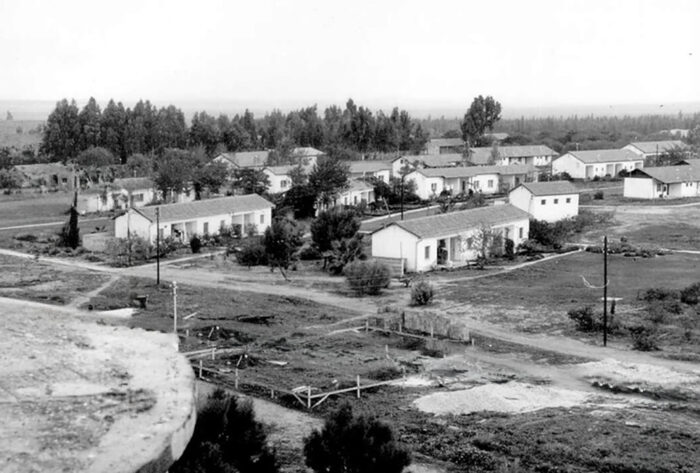

A left-leaning Zionist, Tibon settled in Nahal Oz because he was attracted to its simple sylvan beauty and believed that border communities were essential to securing Israel’s existence as a Jewish and democratic state. Like Tibon, most of its residents were in favor of a peaceful accommodation with the Palestinians. The “only way to ensure real security for Israel was to make peace with all its neighbors, most importantly with the Palestinian people,” he writes in a sensible passage that encapsulates his views.

Tibon, however, had no illusions about his Palestinian neighbors in Gaza, knowing full well that Israel’s arch enemy, Hamas, was intent on wiping out Nahal Oz and all the other communities around it as part of its concerted campaign to destroy Israel.

Nahal Oz was established in the northern sector of the Negev Desert by about 60 soldiers in 1951. Their task was to protect the border, which was nothing more than a ditch along the armistice line that Israel and Egypt had agreed on after the 1948 War of Independence. Israel’s intention from the outset was to convert this makeshift settlement into a kibbutz. This happened in 1953. Since then, Nahal Oz’s economy has been based on agriculture, a dairy and a metal works factory.

Its first member to be killed by hostile fire was struck by an Egyptian bullet while patrolling the border. Until the 1967 Six Day War, Gaza was administered by Egypt. In 1956, its security chief, Roi Rutberg, was fatally shot by Palestinian marauders. At his funeral, the commander of the Israeli armed forces, Moshe Dayan, delivered a memorable eulogy, “The Gates of Gaza.”

Despite Rutberg’s untimely death, Gaza was mostly quiet in the years before the Six Day War. It degenerated into a hotbed of Palestinian resistance following Israel’s occupation.

Israel built a security fence around Gaza and fortified the border after the 1993 Olso peace accord. But in 2001, during the second Palestinian uprising, Hamas rendered the fence virtually obsolete by firing a rocket over it at Nahal Oz. It was the first of many rockets that would be launched from Gaza by Hamas and its sister organization, Islamic Jihad.

The kibbutz was hopeful that Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 would lead to a period of tranquility, but Hamas had other plans. In 2008, Nahal Oz was hit by a major barrage of rockets, touching off the first of several cross-border wars, which erupted in 2012, 2014 and 2021 as Hamas continued to build an enormous arsenal of weapons and a network of attack tunnels in Gaza.

In the aftermath of the 2014 war, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu adopted a new approach to Hamas, allowing Qatar to funnel money into Gaza to avert a humanitarian crisis and another round of fighting. Netanyahu was also determined to widen the split between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority to ensure that a two-state solution remained impossible.

For a while, his policy worked, though it was clear that Hamas was siphoning off Qatari funds to build its military capabilities. Netanyahu’s tactic incensed his defence minister, Avigdor Liberman. “What we are doing right now is buying short-term quiet at the price of our long-term national security,” he said.

Indeed, Hamas was preparing for war. In a speech prior to October 7, Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar warned Israel that his fighters would “come to you … in a roaring flood.” Netanyahu treated his threat as empty bravado, claiming that Hamas was “deterred and afraid of us.”

During this period, Nahal Oz held fast to its belief that its rapid-response force would be able to fend off invaders until the arrival of the army from a nearby base. But on October 7, the members of this force were all in safe rooms with their families. “Hamas had effectively disarmed the team before firing a single shot,” says Tibon in a stark commentary.

They soon rushed out to fight the intruders, who were heavily armed with assault rifles, rocket-propelled grenades and anti-tank missiles. In close-quarter combat, they killed almost 30 terrorists. Accompanying them were dozens of civilians, mostly teenagers, who had come to loot.

Tibon’s father, Noam, a retired general who had commanded troops in Lebanon and the West Bank and now lived in Tel Aviv, came to his son’s assistance. En route to Nahal Oz, he passed a scene of carnage. The road was strewn with the corpses of Israeli civilians who had been killed at a nearby music festival, soldiers and policemen who had battled terrorists, and Hamas fighters. Stopping at a roadside bomb shelter, he was aghast to find that it was full of corpses. At another locale, he killed a terrorist.

When he reached Nahal Oz, he saw bodies everywhere. Most were dead terrorists, clad in tactical vests and green headbands bearing Hamas’ insignia. The exterior of his son’s house was pockmarked with bullets. A dead terrorist, an RPG in his hand, lay on Tibon’s front porch.

“The devastation was breathtaking,” says Tibon.

Nahal Oz lost 13 of its members on October 7. Seven were kidnapped. In addition, two foreigners were killed.

After the attack, a kibbutz north of Haifa, Mishmar Ha’emek, invited all the survivors to live there. They were provided with dorm rooms and all the necessities. “The government was nowhere to be seen,” he writes in a bitter observation.

Several months later, 17 older members, the majority in their 80s, moved to a retirement home in Bat Yam, a suburb of Tel Aviv.

These days, only a handful of people can be found in Nahal Oz, working in the cowshed or driving tractors in the fields. Tibon, who still lives in Mishmar Ha’emek, hopes to return to his kibbutz, but he is not certain he will.

During the early months of the war, Tibon supported Israel’s campaign against Hamas. “I was angry over what Hamas had done and scared of how Israeli weakness in the face of that attack would be perceived by our other adversaries in the region. But as a human being, I find it extremely difficult to countenance the level of destruction caused by own country inside Gaza. And as a resident of Nahal Oz who still holds out hope that my family will one day be able to return here, I have to ask myself what will result from all this violence — peace and quiet or more violence?”

In closing, he clings to this pessimistic tone.

“Our own leadership has failed to take responsibility for the biggest security failure in the history of Israel and has refused to apologize for the blood that was spilled under its watch … There are no leaders in the land — not on the Israeli side or on the Palestinian one.”

A year on, the gloom of October 7 still influences Tibon’s thinking.