Marina Rustow belongs to a fairly new school of historians/sleuths who’ve revolutionized the field of medieval Middle Eastern Jewish history.

A Princeton University professor, and one of the recipients of this year’s prestigious MacArthur fellowship, she’s a social historian who’s played a leading role in modernizing Cairo Geniza research.

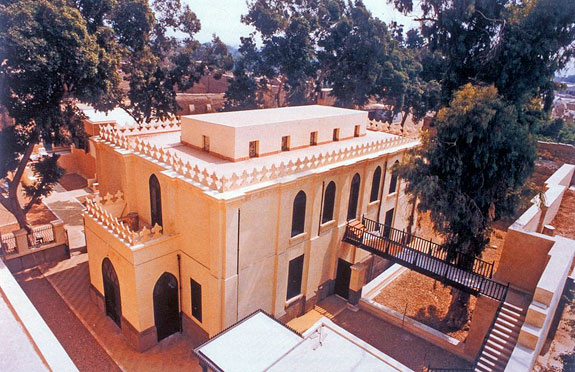

During the Fatimid caliphate, which stretched across the Levant and was headquartered in Cairo, Jews in that bustling city were in the habit of depositing discarded temporal and religious papers in the attic of the venerable Ben Ezra Synagogue.

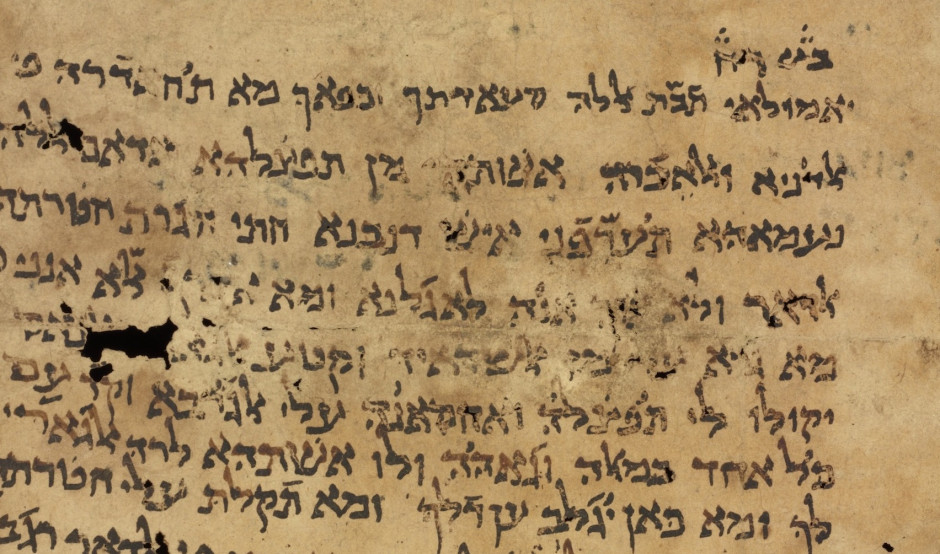

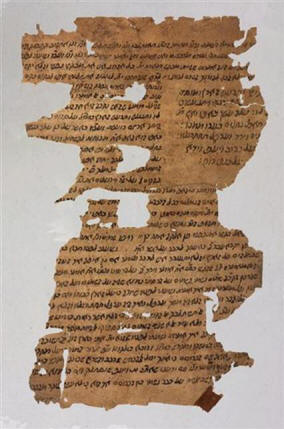

This storage space, known as a Geniza, was filled with a veritable mountain of decaying personal letters and notes, legal contracts, household and communal documents, medical prescriptions, recipes, shopping lists and religious texts — the stuff of daily life.

In 1896, a European scholar stumbled upon this treasure trove. The largest cache of Jewish manuscripts ever discovered, it shed considerable light on medieval Cairo, a hub of trade and commerce in the region and a gateway to the Orient.

Foreign institutions and universities, including Oxford and Cambridge, acquired parts of the Geniza, and its contents were dispersed around the world.

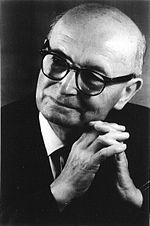

Of all the scholars who worked on deciphering the Geniza’s significance, S.D. Goitein was perhaps the most illustrious one. A German-born ethnographer, historian and Arabist who lived in Palestine/Israel before settling in the United States, he was the author of A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities in the Arab World As Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. Published in six volumes, it’s arguably the definitive work on the subject.

Rustow, who visited Toronto on October 19 to deliver a lecture at the University of Toronto’s Anne Tanenbaum Center for Jewish Studies, credits Goitein with having been instrumental in the development of Geniza studies.

“He gave us a road map,” said Rustow, who, along with other historians, has taken his Geniza research to new levels thanks to the dizzying marvels of digital technology.

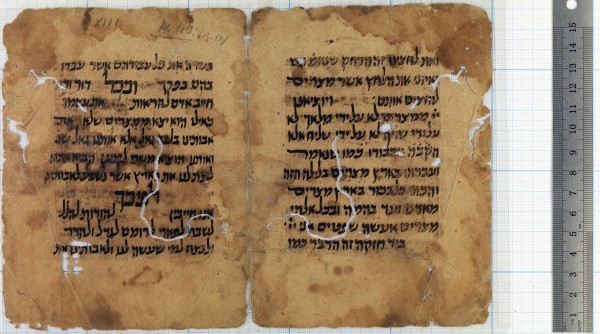

Digitization has had a profound impact on Geniza scholarship, said Rustow, who specializes in the Fatimid dynasty from 950 AD onwards, a period still shrouded in some mystery. Digitization enables scholars to share and compare scattered Geniza fragments. “You can access documents from your living room couch,” she said almost flippantly.

The ability to read these disconnected fragments in a coherent fashion gives scholars a greater understanding and appreciation of the topics they’re studying. Through this collaborative process, renewed interest is sparked in the Geniza.

Rustow, who’s currently writing a book on Fatimid state documents, believes there are 330,000 Geniza folio pages, the bulk of which are in Hebrew script and date from 950 to 1250 AD.

The Geniza’s other claim to fame is that it’s the richest repository of Islamic documents and decrees from this particular epoch. Taking the form of Arabic language petitions from ordinary folks to qadis, or Muslim judges, they deal with matters large and small.

Many of these documents, summoning up a historic period obscured by the passage of time, have yet to be read and analyzed, she said, suggesting that this field of study is still wide open and ready to be ploughed.