Israel’s Arab citizens were placed under military rule from the end of the 1948 War of Independence until 1966. Under this draconian arrangement, they were subjected to nightly curfews, their movements were strictly circumscribed, and they were forbidden to work outside their towns and villages unless they obtained special permits.

This system was overseen by governors appointed by the Israeli government. Regarded as unjust by Arabs, it was seen as a security necessity by Israel. While about 700,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were forced to flee during the 1948 war, upwards of 160,000 chose to remain in Israel.

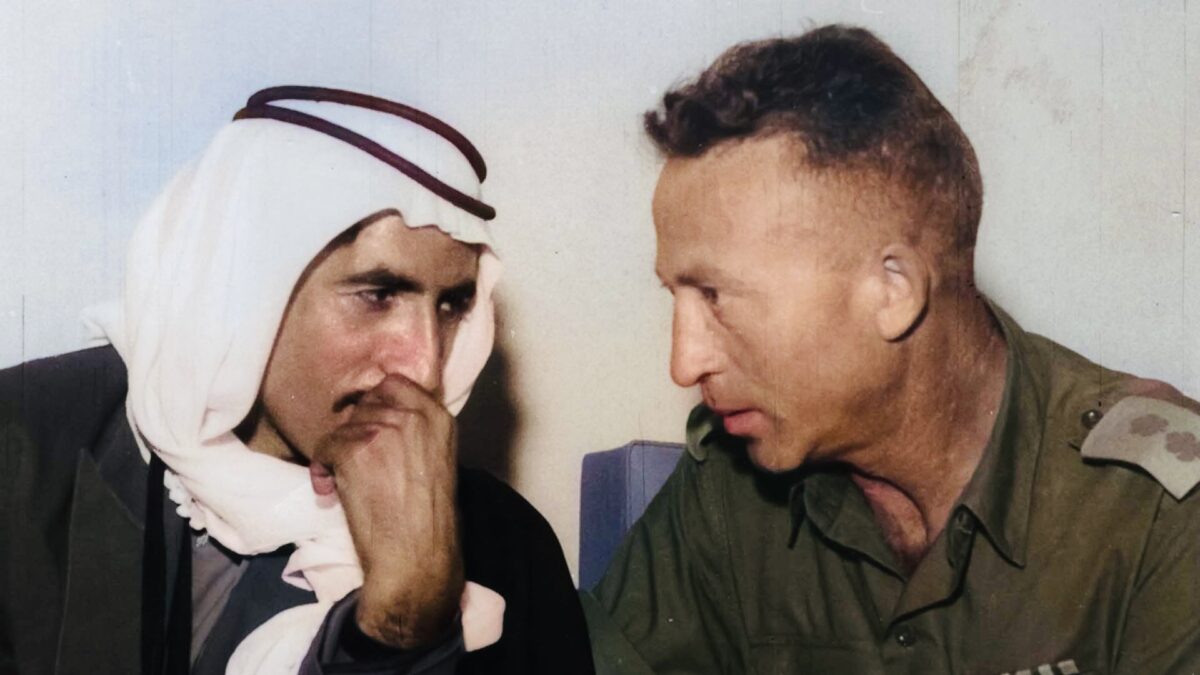

They were granted citizenship, but Israel kept them on a short leash due to its belief that they might be disloyal. The governors who kept watch over them in closed military areas were usually army officers who spoke Arabic and were familiar with Palestinian culture and customs.

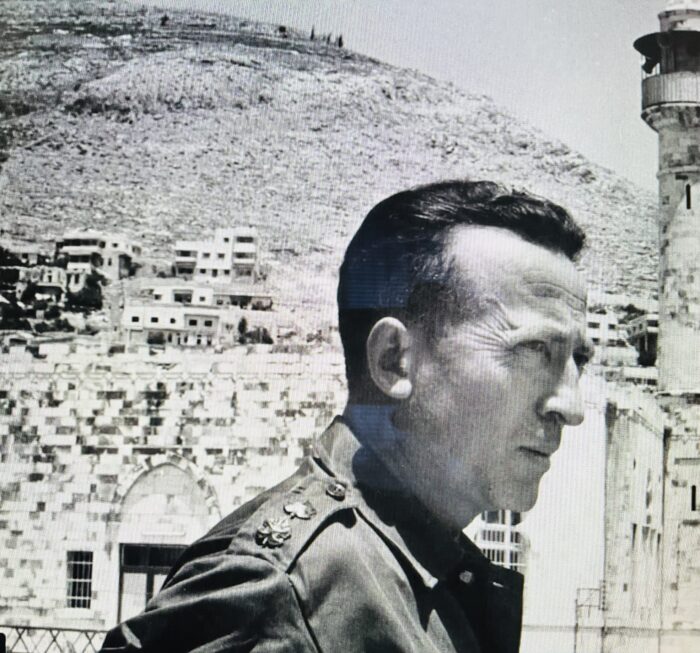

Zvi Elpeleg (1926-2015) was a 24-year-old major when he was appointed governor of three Arab towns in Israel near the West Bank: Tayibe, Tira and Baqaa al-Gharbiyye. He was charged with governing over every conceivable aspect of their lives.

“He was all-powerful,” recalls Ahmed Nimer Hawaja, a resident of Baqaa al-Gharbiyye.

Elpeleg is the subject of The Governor, a fascinating documentary directed by his granddaughter, Danel Elpeleg. It will be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 5-15.

Elpeleg was born in Baranow, Poland, and arrived in Palestine with his parents and siblings in 1934. Raised in Jaffa, a predominantly Arab town adjacent to Tel Aviv, he learned Arabic in his youth.

Judging by the comments of a person who knew him during his governorship, Elpeleg liked imposing his authority. “If you’re in control, they depend on you,” Elpeleg says in a reference to the Arabs he ruled.

As the film suggests, he recruited village chiefs as informers to keep Arabs ostensibly loyal. Out of fear, they celebrated Israel Independence Day, waving the Israeli flag and singing songs about the Land of Israel. And at school, Arab pupils learned only about Jewish and Israeli history. Their teachers were carefully vetted to toe the Israeli party line.

“We had to be strong and protect ourselves,” says Haim Ben-Haim, a former governor, in explaining the rationale for military rule. “We had to put them in their place.”

Elpeleg was so committed to his job that he neglected his wife, Neomi, and persuaded his friend and fellow governor, Israel Krasnansky, to serve as a surrogate husband. As their affair unfolded, Elpeleg took a lover.

This aspect of the film seems superfluous compared to the important topic at hand, but Elpeleg’s granddaughter seems intent on spilling family secrets.

She returns to the matter at hand in an interview with the Israeli historian Gadi Algazi, who describes military rule as mechanism of control and dispossession. Prior to the 1948 war, Jews owned about 7 percent of the land in Palestine. The figure shot up to more than 90 percent after the cessation of hostilities.

By all accounts, more than 500 Palestinian villages were abandoned and destroyed during the war, their inhabitants not being permitted to return.

Elpeleg was an integral part of this system, which was abolished in the face of protests and after Israel’s objectives had been achieved. As an Israeli Arab scholar points out, Israel imposed the same mechanism on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip after the Six Day War.

Elpeleg served as a governor of Nablus and Gaza in the wake of that war. After the wars of 1973 and 1982, he served as governor in Israeli-occupied Egypt and southern Lebanon.

From 1995 to 1995, he was Israel’s ambassador to Turkey. Oddly enough, his granddaughter fails to mention his role in the diplomatic corps. Nor does she cite his authorship of a book about the mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, during the British Mandate era.

Despite these omissions, The Governor is a worthy addition to the pantheon of documentaries about Israel’s mercurial relationship with its Arab citizens.