On July 28, 1959, thieves in Bucharest committed an audacious crime. In broad daylight, they ambushed a truck from the National Bank carrying the equivalent of several hundred thousand dollars in Romanian currency. The theft shocked the Communist leadership and led to the arrest of hundreds of suspects and the production of a unique film.

Shortly after the robbery, five men and a woman were arrested and charged with being the perpetrators. The robbers, all Jews, were members in good standing of the Communist Party and belonged to Romania’s nomenklatura, or ruling elite.

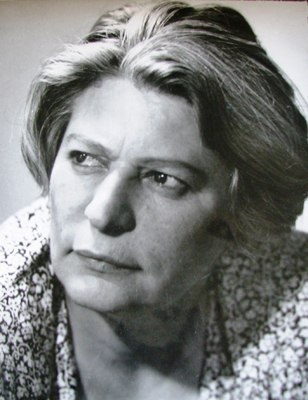

Among the accused were Alexandru Draghici, the former director of the Criminal Police; Alexandru Ioanid, the brother-in-law of the minister of interior, and Monica Sevianu, who had spent three years in Palestine.

Within about six months of the brazen robbery, in one of the most bizarre episodes in the annals of European communism, a state-sponsored “gangster” film of the incident, The Reenactment, was released to the general public.

Astonishingly enough, the “stars” were the robbers themselves, who expected lenient treatment after their appearance in the film. In fact, they were tricked by the authorities into making a full confession, an admission which cut short their lives.

Normally, “gangster” movies were banned in Romania during this period. But this movie was entirely, being nothing more than a propaganda film in service of the regime. Steeped in the usual communist tropes, it was designed to convince Romanian viewers that communism would triumph over capitalism.

The Great Communist Bank Robbery, directed by Alexandru Solomon, skillfully rehashes this strange affair in brisk documentary style. It is currently being screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Foundation.

The question, of course, is why a group of ostensibly privileged Romanians would stoop so low and become common criminals.

During the course of their interrogations, one of the Jewish defendants confessed he had participated in the robbery to help Romanian Jews emigrate. Another participant voiced bitterness that Jews had been dismissed from positions of power in Romania, which persecuted Jews before and during World War II. Still another one characterized the robbery as an act of vengeance in response to the government’s betrayal of Jews.

According to Solomon, the Romanian government lifted the ban on Jewish emigration toward the end of 1958, fully confident that Jews would remain in Romania. But when 100,000 Jews requested permission to emigrate, the regime was outraged, halting further emigration and penalizing those who had registered in the first place.

The Reenactment presented the Jewish defendants as bandits, but omitted their affiliation with the Communist Party and their Jewish background. Nonetheless, the film reinforced the perception among some Romanians that Jews had been instrumental in grafting communism on Romania.

Solomon’s film mentions, among others, Ana Pauker, an arch Jewish Stalinist who was foreign minister from the late 1940s to the early 1950s.

Much to their horror, the defendants were sentenced to death. The men were shot by a firing squad on February 18, 1960. Monica Sevianu, the mother of a child, was spared the death penalty and given a life sentence.

Around this time, Jewish functionaries in two government ministries were sacked, but Jews were allowed to immigrate to Israel. In 1964, Sevianu was released under an amnesty and permitted to settle in Israel. She died there in the 1970s.

The Reenactment was screened for Communist party leaders three weeks after the executions and then distributed to movie theatres across the country.

The Great Communist Bank Robbery, an intriguing film, recreates this long-forgotten footnote in Romanian history.