So much has been written about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, which began 75 years ago on April 19, 1943, the eve of Passover. And yet we continue to write, because of the determination and heroism of the participants.

It was the first popular uprising in a Nazi-occupied city in Europe, and, against incredible odds, lasted almost a month.

But as we commemorate this anniversary, it is also important that we reevaluate the role of the Polish underground during the Holocaust.

A year after invading Poland, Germany set up the Warsaw Ghetto in the heart of the occupied Polish capital in October 1940. Nearly half a million Polish Jews were confined in its squalid quarters, measuring just 1.2 square miles.

Between July 22 and Sept. 21 of 1942, some 260,000 of its inhabitants were deported to the Treblinka extermination camp. They were mainly the elderly or children. After the deportations, 55,000 to 60,000 Jews, mainly younger people, remained in the ghetto and they were concentrated in a few blocks.

The first attempts to establish an armed resistance organization within the ghetto took place even before the deportations. An “anti-fascist bloc” was established between March-April 1942, based on a Communist cell in the ghetto. However, the Gestapo discovered its leader in May 1942 and arrested and murdered him.

Even then, differences remained among the Jews in the ghetto. On the left, there was a long history of rivalry between the Jewish Labor Bund, which stood for a socialist Poland with emancipation of the Jews as a national minority, and the Zionist movements that worked for a socialist or capitalist Jewish state in Palestine.

Representatives of three Zionist youth movements, Hashomer Hatzair, Dror, and Akiva, established the first cell of a new organization. Members of the left-wing Poalei Tzion party joined them in October 1942.

The Bund’s leaders at first refused to join forces with any Zionist parties or movements in creating a united Jewish fighting alliance, claiming they had ties with the Polish underground outside the ghetto. Younger leaders did support an umbrella organization.

Only after the major deportations from Warsaw in October 1942 did the Bund join the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB), which also included Communists. The commander was 23-year-old Mordechai Anielewicz of Hashomer Hatzair.

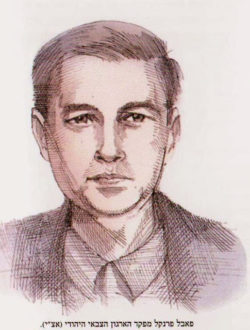

The Revisionist Zionist youth movement Betar remained outside, and established its own fighting organization, the Jewish Military Union (ZZW), led by Pawel Frenkel, also aged 23.

The final German “action” began on April 19. The ghetto population had constructed subterranean bunkers and shelters in preparation for an uprising and had barricaded themselves in these hideouts, taking the Germans by surprise.

The ZOB scattered its positions throughout the ghetto, while the ZZW did most of its fighting at Muranowska Square, impeding the Germans’ attempts to penetrate their defenses.

In response, the Germans began to systematically burn down buildings, turning the ghetto into a firetrap. The Jews fought valiantly for a month, but by May 16 the Germans had crushed the uprising and the ghetto had been burned to the ground.

At least 13,000 ghetto fighters were killed in the battle, almost half burnt alive in the collapsing buildings set on fire by the Nazis.

Surviving ghetto residents were deported to concentration camps, though some managed to escape through underground sewers and took part in the larger Polish rising in the city that began on August 1, 1944.

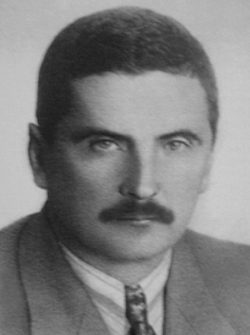

Jurgen Stroop, who had been sent to Warsaw on April 17, was the SS commander who led the Nazi assault on the ghetto. He would write a 125-page document, The Jewish Quarter of Warsaw is No More!, recounting the operation. “The resistance put up by the Jews and bandits could be broken only by relentlessly using all our force and energy by day and night,” he bragged to SS chieftain Heinrich Himmler.

Stroop had joined the SS in 1932. By 1939, he was an SS-oberfuhrer and commander of a police unit. Subsequently, he fought on the eastern front in the Soviet Union. After being wounded, he was transferred to police functions in occupied Poland.

When Friedrich Wilhelm Kruger, the SS and police leader of the Generalgouvernement, decided that the local police commander was not up to the task of liquidating the ghetto, Kruger replaced him with Stroop, who was executed in Warsaw in 1952.

As for the Polish underground, its attitude toward the Jews varied, some elements being more sympathetic than others. There were antisemitic Poles in the resistance who were not unhappy that the Nazis were eliminating Jews from Poland, yet others were horrified at the scale of the genocide.

In his book The Polish Underground and the Jews 1939-1945, Joshua D. Zimmerman, a professor of history at Yeshiva University in New York, maintains that the reaction of the Polish underground to the ongoing catastrophe varied. Alongside those who committed crimes against Jews, even acts of murder, it included heroic individuals who sheltered Jews.

As historian Peter Hayes of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, has suggested in Why? Explaining the Holocaust, the Poles who actively helped to hide Jews and those who persecuted them were actually both minorities.

The Germans made concealing Jews a crime punishable by death for everyone living in a house where Jews were discovered. Yet it is estimated that some 200,000 Poles were engaged in helping Jews despite the threat of execution.

Poland had no collaborationist regime, and the London-based Polish government-in-exile included Jewish representatives on its governing council. This strengthened the support for Jews from within the government. Since the Poles needed Allied support, they had portray their struggle for Poland as a democratic one. Open displays of antisemitism by the Polish underground would have been detrimental to the cause.

The Social Committee to Aid the Jewish Population, later known as the Zegota Council, had been formed on September 17, 1942. A clandestine organization, it ran an extensive network of welfare activities, disseminated information in Poland and abroad regarding the ongoing mass murder of Jews, and demanded strong action against those who denounced Jews.

The major Polish underground force, the Home Army (AK), had 200,000 fighters by the end of 1942. It had counseled Jews against fighting back in cities and camps and had convinced the Bund to vote against beginning a revolt in Warsaw in the summer of 1942. Zimmerman notes that the AK underwent a change of heart. A front-page article in the clandestine AK press on November 4, 1942 called the murders “entirely unprecedented in the history of mankind.”

The AK’s commander, General Stefan Rowecki, came to the conclusion that Jewish resistance groups inside the ghetto deserved assistance. The reason for this authorization, asserts Zimmerman, was a combination of pressure from the Polish government in London and Rowecki’s new appreciation for the demonstrated ability of Jews to fight effectively.

He authorized the transfer of arms, ammunition and explosives to the ghetto beginning in late January 1943. These were essential for the uprising to come. He also approved or ordered actions on behalf of the ghetto fighters. There were even plans to blow a hole in the ghetto wall to allow Jews to escape.

The ZZW now acquired some of their arms from the AK. The ZOB gained some help from the People’s Army (GL) militia, which had been formed by the Communist Polish Worker’s Party (PPR) — a group the anti-Communist AK was at odds with.

The AK had already created a Jewish Department on February 1, 1942, distributing funds and passing on Jewish correspondence to London. In late 1942, an AK courier, Jan Karski, was smuggled in and out of the Warsaw ghetto. He then traveled to London to deliver a report to the Polish government-in-exile and to senior British authorities.

He described the horrors he had seen and warned of Germany’s plans to murder European Jews. In July 1943, Karski even journeyed to Washington and met with American President Franklin D. Roosevelt to give the same warning and plead for action.

When the armed uprising in Warsaw began, news of the battle was sent to the outside world, praising the ghetto fighters. Some AK soldiers would even join the battle. The underground also asked Poles to help any Jews fleeing the ghetto. A Krakow underground paper called the German action “an attack on Poland itself.”

On April 19, during the battle in the ghetto, the ZZW raised two flags atop the highest building in the ghetto: the red-and-white Polish Eagle and the blue-and-white Star of David (today’s Israeli flag).

They were visible in much of the city and many Polish partisans were moved by the gesture. The Polish flag had not been displayed openly since the fall of Poland in 1939. The Home Army called the struggle “worthy of emulation.”

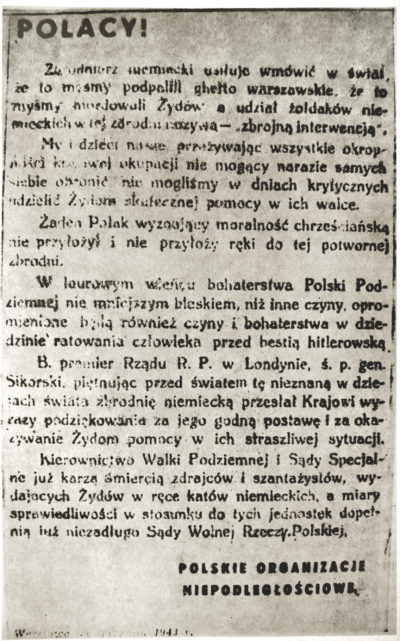

The clandestine press of the Home Army was mostly favorable towards the Jews, reporting accurately on crimes committed not only by Germans but also by szmalcownicy, Polish blackmailers.

The top authorities of the underground issued powerful condemnations of their activities. On May 6, 1943, a declaration was printed in the largest circulation underground papers, condemning them as traitors who would be put to death. Special civil courts were created to prosecute collaborators.

The Warsaw Ghetto uprising became an example for Jews in other ghettos and camps, sparking smaller revolts elsewhere in Poland.

My mother’s two brothers participated in the revolt in Czestochowa. After it ended, they fled into a nearby forest, where they were hunted down and shot by the SS.

Last month, Polish officials held ceremonies honoring Poles who gave shelter and aid to Jews during the Holocaust. It marked the first time Poland had designated a national holiday in their memory. Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said that helping Jews at that time was “one of the most glorious pages of Polish history.”

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.