Holland was liberated by the Canadian army 70 years ago next month after five years of Nazi occupation. The official date of the liberation was May 5, 1945, two days before Germany’s official surrender to Allied forces.

The people of Holland paid dearly for German aggression. By one estimate, 150,000 Dutch civilians perished during this period. This figure not does include the 2,500 Dutch soldiers killed while resisting the 1940 German invasion.

The Jewish community was particularly hard hit by this catastrophic event. In Holland, the Holocaust claimed the lives of 107,000 Jews, or 78 percent of Dutch Jewry, the highest death rate in western Europe.

This statistic is all the more jarring considering the fact that Holland is historically a tolerant nation, having admitted Jews from Spain after the Inquisition and Jews from Germany following the rise of Nazism.

When Germany invaded Holland on May 10, 1940, it was home to approximately 160,000 Jews — 140,000 halachic Jews, 14,000 half-Jews and 5,000 quarter-Jews, comprising about 1.5 percent of Holland’s population of nine million.

Dutch Jews were deported mainly to Auschwitz and Sobibor via the Westerbork camp. Five thousand of the deportees survived their ordeal. Of the 25,000 Jews who went into hiding with the help of Christians, one-third were betrayed and murdered, including Anne Frank, the teenager whose iconic diary was published in a multitude of languages after the war.

Holland, having been neutral in World War I, hoped to stay out of World War II. Adolf Hitler, Germany’s chancellor, had assured Holland he would respect its neutrality. But in a blitzkrieg, Germany broke its promise. The poorly-equipped Dutch fought back valiantly, but could not resist the German tide. On the fifth day of the invasion, Germany bombed Rotterdam, killing nearly 1,000 civilians. Cowed by the threat of further German bombing raids, Holland surrendered.

Germany imposed a Nazi-controlled administration on Holland under the direction of Arthur Seyss-Inquart. At first, Germany respected Dutch laws, pledging not to foist Nazism on the country. It was all a sham. Germany’s long-term aim was to annex Holland.

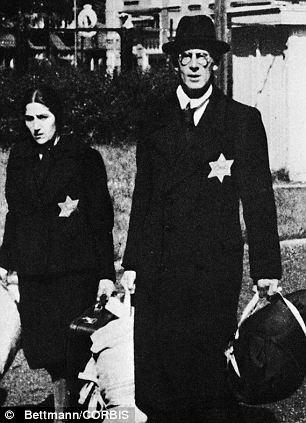

Within two months of occupying Holland, Germany imposed a series of escalating restrictions on Dutch Jews. By 1942, they were forced to wear the yellow Jewish star.

To a degree, the Dutch collaborated and cooperated with the Nazis. With the flight of the royal family to London, where a Dutch government-in-exile was established, senior Dutch civil servants administered Holland in conjunction with the Germans.

On a more sinister level, 25,000 Dutchmen served in the Waffen-SS, which participated in atrocities against Jews on the eastern front in the Soviet Union. Dutch police assisted the Germans in the roundup of Jews, and the Dutch Nazi Party, under the leadership of Anton Mussert, collaborated with the Nazis.

On the bright side, Dutch workers staged a sympathy strike in support of Jews in February 1941. And in 1942, Protestant and Catholic clergymen sent a telegram to the Germans protesting the deportations of Jews. Meanwhile, the Dutch resistance movement aided Jews, while the Dutch government-in-exile denounced the antisemitic edicts.

All too often, though, the extermination of Dutch Jewry was greeted by indifference. After the war, Jewish survivors were generally met with a cold and bureaucratic reception by the Dutch government.

Charlotte van den Berg, a researcher, has found letters from survivors in Amsterdam’s city archives complaining they had to pay back taxes and late payment fines on property the Nazis had seized from them.

Reviewing this data, the Netherlands Institute of War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies uncovered 217 cases in which returning Jews had to make these payments. Amsterdam’s legal office advised the municipality not to enforce the fines, but the recommendation was rejected.

“The city made a conscious decision to reject this advice, which cannot be described otherwise than as a totally needless callousness toward (Jews) who had their property taken during the war,” the newspaper De Telegraaf reported.

Stubbornly enough, Amsterdam officials decided in 1947 that the city had “the right to full payment of fees and fines,” the Nazi occupation notwithstanding.

In some cases, Dutch collaborators who had bought Jewish-owned homes for undervalued prices left their utility bills unpaid. After they had fled Holland, Jews received invoices for the natural gas they had used.

These acts of insensitivity continue to this day.

The Jewish Telegraphic Agency recently reported that the mayor of Geffen, a town 60 miles southeast of Amsterdam, scrapped a controversial plan to build a monument bearing the names not only of Holocaust victims, but of Dutch soldiers who had died fighting on behalf of Germany.

An uproar ensued and the monument was redesigned to carry the names of Dutch Jews who had been murdered during the Holocaust and the name of a local man who had enlisted in the German army and had been killed in action.

The redesign has been hostly contested by Holland’s Jewish community.

In another controversy, a monument bearing the names of the Dutch victims of the Holocaust has been put on hold. Supposedly the first one of its kind in Holland, it was designed by the Polish-born American architect Daniel Libeskind, and was to have been erected in a park in Amsterdam this year.

Residents of the neighborhood protested, saying that they had not been consulted and that the monument was far too big for the space allotted.

The project has been sent back to the drawing boards, leaving a bitter taste in the mouths of some Jews.