Despite its best efforts, the United States and its allies have failed to stop the Houthis from disrupting the flow of commercial shipping in the Red Sea, one of the world’s busiest sea lanes.

Hundreds of tankers thereby have been redirected to the longer and more expensive Cape of Good Hope route around South Africa, bringing down Red Sea traffic by more than 40 percent and virtually crippling operations in the Israeli port of Eilat, which is located on the northern tip of the Red Sea.

These attacks have raised insurance rates, increased the price of consumer goods, and driven up global inflation.

Some of the world’s biggest container shipping companies, notably Maersk, have suspended sailings through the Red Sea, which connects Asia to Europe and the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal in Egypt.

Prior to the current war in the Gaza Strip, which broke out after Hamas terrorists killed roughly 1,200 Israelis and foreigners on October 7, around 12 percent of the world’s shipping passed through the Red Sea. On average, about 50 ships entered this body of water per day, carrying between $3 billion to $9 billion worth of cargo valued at more than $1 trillion dollars per year.

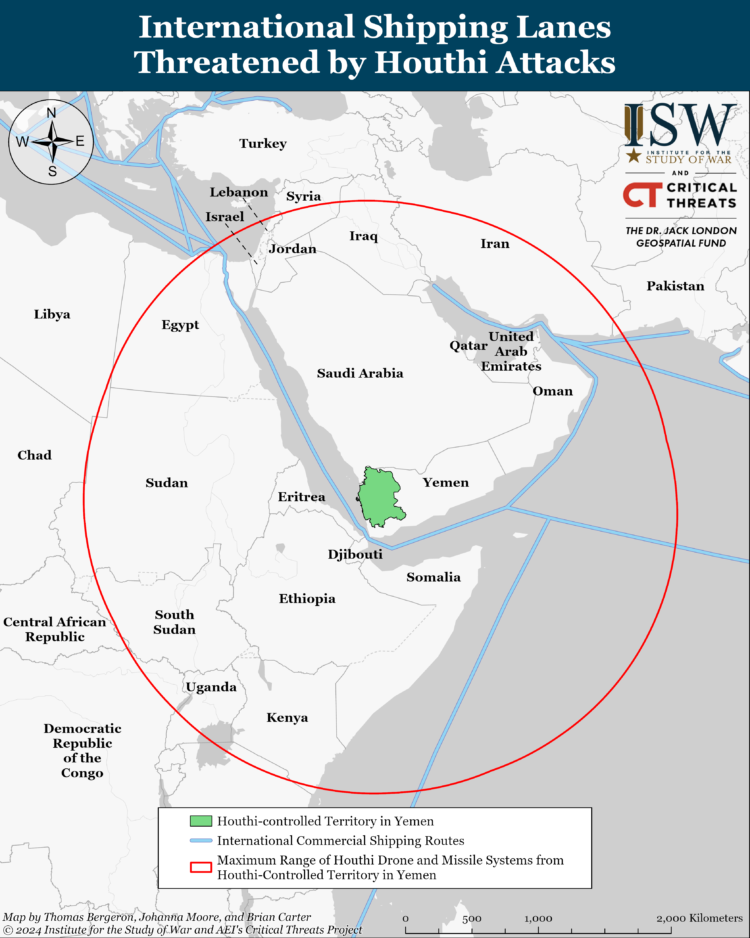

Since the eruption of the war, the Houthis — a Yemenite rebel group backed by Iran and at odds with Yemen’s internationally recognized government in the southern part of the country — have fired countless missiles and drones at merchant and naval ships in the Gulf of Aden, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the Red Sea.

Last November, they seized the Galaxy Leader, a car transporter bound for India, and its crew.

The Houthis claim they are acting out of solidarity with Hamas and will only cease their attacks after the war in the Gaza Strip ends.

At first, they announced that only vessels connected to Israel or en route to Eilat would be targeted. Then they said that American and British ships also would be attacked. Since then, they have placed the ships of many nations, including a vessel carrying Russian oil, in their crosshairs.

On March 21, the Houthis said they had reached an agreement with Russia and China to assure the safe passage of their ships through the Red Sea. But just two days later, a Chinese vessel was struck by a Houthi missile.

The Houthis ignored this warning and continued attacking ships in the Red Sea, prompting the United States on January 13 to intensify its retaliatory air raids in Yemen.

U.S. and British aircraft bombed Houthi command centers, air defences, munition depots, and drone and missile production and storage facilities. The objective was to damage the Houthis’ ability to launch fresh attacks, but the strikes damaged or destroyed only about one-third of their offensive capabilities.

The United States and its allies have since struck Houthi targets again and again, but to no avail. After one of the most recent raids, the Pentagon’s deputy press secretary, said in resignation, “We know that the Houthis maintain a large arsenal. They are very capable. They have sophisticated weapons.”

As analysts have noted, the U.S. campaign to degrade the Houthis’ military capabilities is not only onerously expensive but even perhaps impractical, since it takes multimillion-dollar missiles to destroy cheaply-made Houthi drones and missiles.

Having survived the U.S. onslaught, the Houthis have been emboldened to launch yet more provocative attacks.

On February 18, a Belize-flagged ship, the Rubymar, was attacked in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. After taking on water, the Rubymar sank in the Red Sea on March 2, becoming the first vessel to be fully destroyed by the Houthis.

On March 6, three sailors aboard the True Confidence, a Liberian-owned, Barbados-flagged ship, were killed when it was hit by Houthi missiles in the Gulf of Aden approximately 93 kilometers off the coast of Aden. They were the first seafarers to be killed by the Houthis.

Three days later, U.S., British and French forces repelled a series of Houthi attacks off the coast of Yemen, downing 28 drones over the Red Sea. The Houthis had targeted the Propel Fortune, a cargo ship, and several U.S. destroyers.

Four days ago, U.S. forces engaged six Houthi drones over the southern Red Sea, intercepting five of them.

On the same day, a Chinese-owned and Panamanian-flagged oil tanker, the Huang Pu, was attacked by Houthi ballistic missiles. The assault caused a fire that was extinguished by the crew.

The Houthis, on March 26, claimed they had conducted five drone and missile attacks against civilian and military vessels from Malta, Panama, Singapore and the United States.

From day one of their illegal campaign to interfere with shipping in the Red Sea, the Houthis have consistently targeted Israel. This is hardly surprising, given their incendiary slogan: “Death to America/Death to Israel/Curse upon the Jews/Victory to Islam.”

The Houthis, members of the minority Zaydi sect in Shi’a Islam, began attacking Israel on October 19, exactly 12 days after Israel declared war on Hamas and initiated its bombing of Gaza. On that day, the Carney, a U.S. destroyer, shot down four Houthi missiles and 15 drones, all of which were apparently aimed at Israel.

The Houthis have since fired yet more missiles and drones at Israel, but they have all been intercepted.

On March 19, however, a Houthi missile crashed into a field near Eilat, the first time one of their projectiles landed in Israeli territory.

Due to Houthi aggression and the United States’ failure to deter the Houthis, Eilat’s commercial shipping traffic has dropped by 85 percent in the last few months, forcing authorities to sack half of its 120 port workers.

Eilat, Israel’s gateway to Asia, is an important port, handling car imports and potash exports. Presumably, the slack will be taken up by the ports of Haifa and Ashdod.

Egypt, too, has been adversely affected by the crisis in the Red Sea, with revenues from Suez Canal transit fees having sharply plummeted. This financial hit partially explains why Egypt has been in the forefront of promoting a ceasefire to end the Gaza war.