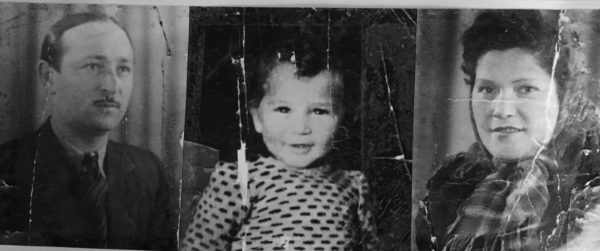

My parents, David and Genia, passed away in Toronto in 2016, leaving two less Holocaust survivors in a dwindling population of some 400,000 around the world.

Mostly in their 80s and 90s, they are the last living links to an unprecedented tragedy — the systematic, industrial-scale extermination of six million European Jews from 1939 to 1945. Jewish history is replete with antisemitic massacres and pogroms, but nothing can compare to what unfolded during the Holocaust, which was perpetrated by Nazi Germany in tandem with complicit fascist states such as Hungary, Romania, Italy, France and Slovakia.

My late parents lived to ripe old ages and were loved and appreciated by their three children and grandchildren, but they were deeply affected by the physical and mental horrors inflicted on them by their tormentors. They were members of a tragically unique generation of European Jews who had the misfortune of having been born and brought up in the wrong countries at the wrong time.

I grew up with stories about the Lodz ghetto, where they were incarcerated until its dissolution in August 1944, and Auschwitz-Birkenau, one of the Nazi extermination camps to which they were transported in cattle cars.

My mother never really recovered from the searing loss of her five-year-old son in Auschwitz, and the eternal sadness in her eyes was a reflection of her grief. My father, a blue Nazi tattoo burned into the underside of one of his arms, was more willing to talk about the past. He recalled his military service in the Polish army during the German invasion of Poland. He described his job as a fireman in the ghetto. He fleshed out the details of his heroic rescue of his two younger sisters during a deportation.

As I took it all in, I made a pledge to myself never to forget their profound pain and sorrow. Raised on this regimen of Holocaust recollections, I deposited them in my memory bank, steeped myself in the growing literature of the Holocaust, and never lost sight of the chilling thought that if I had been born a few years earlier, I may well have been added to that grim list of 1.5 million Jewish children who perished during that awful period.

As time flies, there are considerably fewer Holocaust survivors, the greatest number of whom live in Israel, the United States and countries like Canada, Australia, Britain and France. Which means that there are significantly fewer witnesses who can tell their incredible tales of survival on a first-hand basis to their children, grandchildren, Holocaust organizations, school assemblies, journalists and historians. Once they’re gone, their voices will forever be stilled, and the Holocaust will gradually fade into the vast stillness and dimness of obscurity.

Regrettably, this process already has begun.

A study in 2018, commissioned by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, found that many adults lack basic knowledge about this event, and that this scarcity of knowledge is more pronounced among millennials between the ages of 18 and 34.

“The issue is not that people deny the Holocaust,” Greg Schneider, the executive vice-president of the Claims Conference, was quoted as saying. “The issue is that it is receding from memory.

Ignorance of the Holocaust has consequences.

With xenophobia, racism and antisemitism on the rise, there is a pressing need for Holocaust education in schools. Such history lessons, taught by competent teachers, could be an effective antidote to all these ugly ills. They could also, perhaps, mitigate the effects of malicious Holocaust deniers, who never miss an opportunity to belittle and demonize Jews.

With this in mind, I commend the U.S. House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. for having passed legislation recently to allocate $10 million in federal finding over five years to further Holocaust education. Proposed by New York Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, the Never Again Education Act was passed by a margin of 393-5, and would funnel funds to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s education program. The U.S. Senate is scheduled to consider the bill in the near future. Then it is supposed to be signed by President Donald Trump.

“I can think of no better way to honor the memories of those murdered than to make sure our students know their names and stories,” said Maloney. “If we do not learn from history, we are doomed to repeat it.”

Exactly right.

If we forget the lessons of the Holocaust, we are surely destined to stumble into madness yet again.