The Holocaust was set in motion not by one single momentous decision, but by several key events. The Wannsee conference of January 20, 1942 was one of those pivotal moments, or turning points, in Nazi Germany’s inexorable march toward genocide.

Eighty years on, British historian Peter Longerich has written Wannsee: The Road to the Final Solution (Oxford University Press), an austerely sober, concise, yet comprehensive account of this diabolical meeting, which took place in a luxury villa next to a small lake in Wannsee, an upscale suburb in western Berlin.

Fifteen officials of the regime, the Nazi Party and the SS attended. Their host, Reinhard Heydrich, was chief of the Reich Security Head Office and the Protector of Nazi-occupied Bohemia and Moravia.

Unbeknownst to him, his days were numbered. On May 27, he was seriously injured by Czech partisans in an assassination attempt in Prague. He died of his wounds on June 4, and Adolf Hitler gave him a state funeral.

Heydrich was delegated to organize the conference by Hermann Goring, Hitler’s second-in-command, on July 31, 1941. By that point, Germany had invaded the Soviet Union and killed tens of thousands of Jews.

The surviving minutes of the one-and-a-half-hour conference indicate that it was called to discuss the “final solution to the Jewish question,” which obsessed Hitler and his associates.

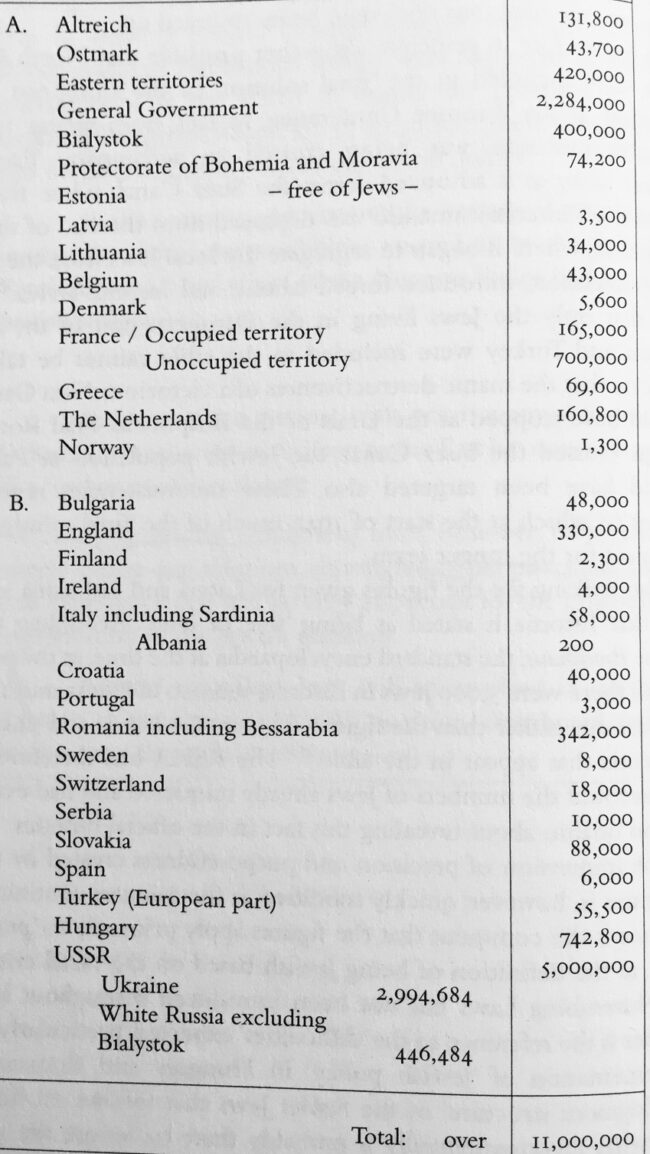

Its objective was to ascertain who precisely was to be killed and what methods would be used to deport a total of eleven million Jews throughout Europe. Among the eleven million were the Jews of neutral countries: Sweden, Ireland, Portugal, Switzerland, Turkey and Spain. If the German army had reached Palestine, Jews there would have been murdered, too.

“The minutes are unique because, more than any other document, they demonstrate with total clarity the decision-making process that led to the murder of the European Jews,” he writes in a bold-face passage.

Longerich, a professor of modern German history at the University of London, is painstakingly precise. He points out that no concrete decision to exterminate the Jews of Europe was taken at the conference. Its purpose was to create the master plan for the impending industrial scale slaughter.

As Longerich suggests, the invitees were not necessarily crude or uneducated. Ten were university graduates, eight had earned a doctorate, and nine were lawyers. They expressed different views concerning details, but none raised concerns about the mass murder they were planning.

Among the participants were Martin Luther, the undersecretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Adolf Eichmann, a senior Gestapo functionary; Otto Hofmann, the director of the SS Race and Settlement Department; Alfred Rosenberg, the minister in charge of the conquered eastern territories; Georg Leibbrandt, one of Rosenberg’s deputies; Wilhelm Stuckart, a state secretary at the Ministry of Interior; Leopold Gutterer, a representative of Josef Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda, and Ulrich Greifelt, a senior SS official in charge of “consolidating the German ethnic nation,” in the words of SS chieftain Heinrich Himmler.

The conference demonstrates that the Holocaust was not just the work of the Nazi Party and the security services, but rather a collaborative effort of the state and a host of ministries.

After the war, most of the participants who could be questioned claimed they could hardly remember the conference, or denied ever being there. Friedrich Kritzinger, a deputy state secretary in the Reich Chancellery, was the only attendee who admitted what was discussed and who showed remorse.

Heydrich issued the invitation to the conference on November 29, 1941, about a week before Japan attacked the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor and Germany, its ally, declared war on the United States.

Germany’s Jewish policy had reached a critical stage by late November. Germany’s original plan had been to deport Jews to the newly occupied eastern territories after the Soviet Union’s defeat. “But the military situation made this a distant prospect,” Longerich says. “At the same time, the shootings of Jewish civilians in the Soviet Union, and in Serbia too, had reached such proportions that those responsible saw an opportunity to accomplish the ‘final solution’ in these territories even before the end of the war.”

The conference was the logical extension of Nazi antisemitism, Longerich reminds a reader. From the outset of his chancellorship, Hitler was determined to remove Jews from Germany. Prior to the outbreak of World War II, the most important steps in this process were the boycott of Jewish businesses in April 1933, the Nuremberg Laws of September 1935, and the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, he says.

In the wake of Kristallnacht, Goring — the commander of the Luftwaffe — was given the job of removing Jews from the economy and of managing “Jewish policy.”

By 1939, 250,000 German Jews had emigrated, leaving nearly 200,000 Jews in Germany. And once Germany had invaded Poland, igniting the world war, three million Polish Jews fell into its hands. Germany had to deal with yet more Jews following its invasion of the Soviet Union.

Initially, the Nazi regime sought a “territorial solution,” hoping to establish a Jewish “reservation” in the Lublin district. This scheme, however, clashed logistically with the mass resettlement of ethnic Germans from the Baltic states in this Polish district.

A plan to resettle four to six million Jews on the French colonial island of Madagascar was promoted by the Jewish department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. According to Longerich, the Nazis reckoned that desperate conditions, combined with punitive measures, would result in the physical annihilation of the Jewish deportees. By the summer of 1940, the plan was abandoned because the tropical island remained inaccessible to Germany.

Early in 1941, Himmler asked the organizer of the notorious euthanasia program to prepare a plan for the mass sterilization of Jews. Detailed scenarios were sent to Himmler, but he did not pursue this project further.

As Germany geared up for the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, one of its main aims was to systematically eradicate the “Jewish-Bolshevist intelligentsia.” The task was assigned to four Einsatzgruppen units, 23 battalions of the Order Police and three SS brigades.

At first, Jewish men of military age were killed. Then Jewish women and children were targeted. By the end of 1941, at least 500,000 Jewish civilians had been shot in the so-called Holocaust of the bullets, he estimates.

Germans Jews were targeted for deportation in the same year. The deportations started on October 15 in Berlin. The first batch of deportees were transported to Poland and Latvia. Eight days later, Germany banned the emigration of its remaining Jews. During this period, Czech and Austrian Jews were deported as well.

With deportation trains from Germany arriving in Poland, the Criminal Police Institute in Germany developed a new killing machine, the gas van. It was first used in Chelmno in December to murder inhabitants of the Lodz ghetto. In the Auschwitz concentration camp, meanwhile, experiments were conducted with Zyklon B, a highly toxic disinfectant that, ironically, had been discovered by a German Jewish chemist. The first victims of Zyklon B were captured Red Army soldiers.

Two days before the first Jewish deportees left Berlin, Himmler instructed one of his deputies, Odilo Globocnik, to build the first extermination camp in Poland. Construction of Belzec got underway in November. Sobibor and Treblinka were built in the spring of 1942, when the Nazis envisaged the mass murder of Polish Jews. By then, the German company Topf and Sons had received a contract to build a crematorium complex with 15 furnaces in Auschwitz.

Cognizant of these events, Frank told colleagues toward the end of 1941, “We must destroy the Jews wherever we find them and whenever possible.” On November 16, 1941, Goebbels published an article in Das Reich recalling Hitler’s “prophecy”of January 30, 1939, in which he predicted the wholesale destruction of Jews. “We are now seeing the fulfillment of this prophecy,” he wrote in gloating fashion. “Jewry is now undergoing a gradual process of annihilation.”

Two days later, at a press conference designated as “confidential,” Rosenberg spoke of the “biological eradication of the entire Jewish population of Europe.”

When the Wannsee conference was convened, the stage already had been set for the Holocaust. Or as Longerich puts it, “The Nazi leadership’s original intention to leave the ‘final solution’ until after the war already had been abandoned.”

One of the issues discussed at the conference was the treatment of “mischlings,” or Germans of mixed Jewish-Christian descent. A person who had two Jewish grandparents but did not belong to the Jewish religious community was classified as a “1st-degree mischling.” A person with one Jewish grandparent was deemed as a “2nd-degree mischling.” Several hundred thousand mischlings lived in Germany in 1942.

It was decided that mischlings, unlike full Jews, would be allowed to remain in Germany, but would be subjected to sterilization and a wide range of discriminatory measures.

Ten days after the conference, Hitler declared, “We are fully convinced that the war can end only with the extermination of the Aryan nations or the disappearance of the Jews from Europe.”

In May and June of 1942, the Nazis intensified their murderous rampage, having decided that Russian Jews would be killed inside the Soviet Union, while Jews in the rest of Europe would be murdered primarily in extermination camps on Polish soil.

Several days after Heydrich succumbed to his wounds, roundups of Jews in France, Holland and Belgium occurred. By September, more than 250,000 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto had been deported to and murdered in Treblinka. By then, Germany had asked its allies, Romania, Croatia and Finland, to give up their Jewish citizens.

In retrospect, then, the Holocaust was in full swing in the summer of 1942, just six months after the conference.

In summing up, Longerich writes, “The significance of the Wannsee conference lies … in the fact that it reflects a radical revision in the thinking of the German leadership about the future direction of ‘Jewish policy’ and about what the ‘final solution’ involved.” In other words, the “final solution” became an integral component of Germany’s war aims.

He emphasizes that Heydrich, Himmler and Goring acted in close consultation with Hitler, who always authorized “every important measure” dealing with Jewish policy.

As other historians have said, Hitler was inextricably bound up with the Holocaust.