Possessing the largest concentration of Iranians outside the Islamic Republic of Iran, Los Angeles could well be called Little Iran. More than 70,000 of these exiles are Jews, and one of them, Saba Soomekh, is a religious studies scholar who teaches at the University of California in Los Angeles.

Born in Tehran in 1976, she and her family immigrated to the United States in 1978, a year before the pro-U.S. Pahlavi monarchy of Mohammad Reza Shah was swept away by an Islamic coup.

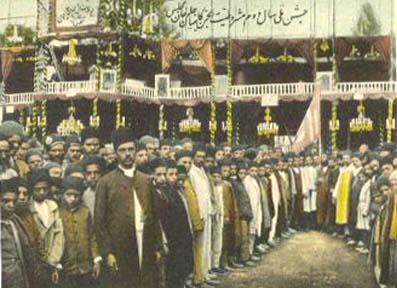

Soomekh has written an ethnographic study of Iranian Jews in Los Angeles, who comprise a substantial chunk of its long-established Jewish community. From the Shahs to Los Angeles (State University of New York Press) is a penetrating portrait of three generations of Iranian Jewish women who were affected by three seismic developments in Iran’s history: the Constitutionalist revolution of 1906, the Mohammad Reza Shah period (1941-1979) and the Islamic revolution (1979 to the present).

Iranian migration to America came in two waves. Before 1979, the majority of Iranians who arrived were students majoring in technical fields. After 1979, the migrants tended to be political exiles opposed to Ayatollah Ruhollah Mousavi Khomeini, the spiritual leader of the new order.

Iranian Jews who fled had good reason to leave, she observes. Due to their “prominent socio-economic status, their identification with the shah and his policies, and their attachment to Israel, Zionism and America,” they believed they would be mistreated by the Islamic regime.

In general, Jews in Iran were religiously observant, traditional and insular. The first generation of women Soomekh interviewed regarded the preparation of Sabbath meals as a way to maintain their Jewish identity. “Keeping kosher was so important that Iranian Jews would never eat food from a Muslim, Christian, or member of the Baha’i faith,” she adds.

Arranged marriages were the norm, as one woman told her. “Basically, we married the man our parents thought would give us the best life, the man who came from a family with a good reputation. There was no such thing as dating, or finding your soul mate.”

Virginity was a prerequisite for a new bride. As Soomekh puts it: “When women got married, they had to prove their virginity to their mother-in-law by showing her a bloodstained sheet after the wedding night. This practice became mostly obsolete in Iran by the late 1960s, yet the importance of virginity was, and still is, incredibly important.” To this day, mothers urge daughters to be najeeb (virginal, pure and innocent).

For centuries under Muslim law, Jewish women were required to wear headscarves. Many found it very difficult to remove them once they were banned in 1936. And while Muslim feminists criticized the shah for having forced them to embrace modernity, secularism and Westernization, Jewish women praised him for having modernized Iran and allowed Jews to flourish in Iranian society.

In her estimation, the Pahlavi epoch was a golden era for Jews. “The Iranian Jewish community went from being an oppressed and poor community to being an affluent and well-integrated one. Under the shah, many Jews left the mahalleh (the Jewish ghetto), assimilated more into Iranian culture, and were able to practise their religion in a less antisemitic milieu,” says Soomekh.

Emancipation went only so far. “The Jews of Iran never truly assimilated into Iranian society,” she claims. “There were limits placed on how successful they could become in their professions … and they remained exclusively bound to their own community and Jewish identity.”

With integration, however, fears emerged that Jewish women would marry Muslim men. “Even women from the most secular families disapproved if their daughters intermarried,” she notes.

In any event, few Jewish women could aspire to careers. Most went to high school and got married shortly thereafter.

For women growing up during the Pahlavi interregnum, physical beauty was of paramount importance. As a result, many turned to rhinoplasty, a surgical procedure that remains popular today in Los Angeles.

Smoking in public became fashionable, too. “Under the shah’s regime, a Jewish woman who smoked was seen as being more acculturated and Europeanized,” she says.

Many second-generation Iranian women worked at jobs to help support their families. For some, working outside the home enhanced their self-image.

Although virginity is still regarded as a virtue, especially among young Orthodox women, it’s not always observed by their secular countereparts. Ashley, a 18-year-old high school senior, told Soomekh: “A lot of Iranian Jewish girls are having sex at 15 and 16 … There is a backlash against being najeeb.”

In her view, Iranian Jews place a premium on conspicuous consumption. “This is a community where the area code one lives in, the car one drives and the purse one totes carry a lot of weight,” she writes. As one woman admitted, “The materialism in our community has only gotten worse and more out of hand.”

Ideas of feminine beauty have remained constant. “Women who are lighter-skinned and have less Semitic but more Anglicized features are traditionally considered to be the most attractive. The ideal bride/daughter-in-law is described as zagh o boor, meaning she has light eyes and light hair. Yet at the same time, traditional Iranian features, such as almond-shape eyes, thick but nicely defined and groomed eyebrows and hair, and long, dark eyelashes, are believed to be attractive physical traits.”

Soomekh contends that marriage liberates the typical Iranian Jewish woman. “When a woman is in her father’s house, she must act like the proper Iranian Jewish girl in order to find a good husband. When she marries, she is free to travel, go out late at night and do all the things that are considered improper for a najeeb girl to do. Once she is married, the family does not have to worry about her reputation, and she has the freedom to do what she wants because it is assumed that she is now under the guidance and watchful eye of her husband.”

Third-generation women are expected to not only attend college, but to have a career following graduation. Many have pursued careers in medicine, psychology, science, dentistry, academia and real estate, but they’re still judged on the basis of their marital status. “Thus, a woman can be one of the top female doctors in Los Angeles, but she is still seen as being a more accomplished woman if she marries a top doctor.”

Sexual modesty is still an important trait among this group, but some women are of the opinion that the concept of najeeb has become archaic.

Arranged marriages seem to have faded away. “The third generation has more freedom in regard to their selection of mates,” she says. Women can meet their husbands-to-be in school, through friends and at parties.

“One aspect of the Iranian Jewish community that has not changed is its emphasis on a woman’s physical traits and on materialism,” she points out. “A pilgrimage to the Gucci boutique has replaced the pilgrimage to Esther’s tomb.”

So while Iranian Jewish women in Los Angeles have transformed themselves in some key respects, they remain quintessentially Iranian in terms of their values, customs and expectations.