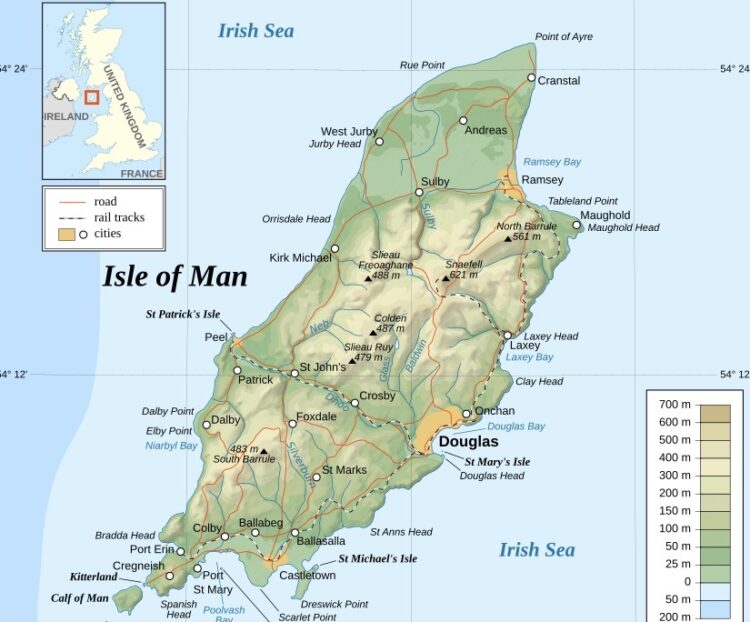

Shortly after his appointment as prime minister in 1940, Winston Churchill ordered the detention of thousands of German and Austrian Jewish refugees who had fled to Britain to escape Nazi persecution. Known as enemy aliens, they were rounded up in the prevailing belief that German spies in the country posed a security threat to Britain. Arrested without charges or trials, they were confined to prison camps such as Camp Hutchison on the Isle of Man. One of ten such internment camps on this Irish Sea island, it held about 1,200 prisoners.

Two weeks before the first detainees arrived, German troops occupied the island of Jersey, which, like the Isle of Man, was a self-governing British crown colony.

Camp Hutchison, which was officially opened on July 13 of that fateful year, housed “one of history’s unlikeliest and most extraordinary prison populations,” writes Simon Parkin in his comprehensive account, The Island of Extraordinary Captives (Scribner).

Among its detainees was Peter Fleischmann, a young German Jew who reached Britain before the war via the kindertransport special placement program. Later, he would anglicize his surname to Midgley. Fleischmann, an orphan following the death of his parents in a freak car accident, briefly stayed with his grandfather, Alfred Deutsch, a retired banker. After leaving Deutsch’s home, he decamped in a shelter for Jewish refugees.

While Parkin focuses on Fleischmann’s checkered odyssey in Britain, he devotes much of his narrative to Britain’s policy toward Jewish refugees, who unfairly would be categorized an enemy aliens.

Originally, out of sympathy with the Jewish victims of Nazi oppression, the government allowed the first Jewish minors from Germany and Austria into Britain in 1938 within the framework of the kindertransport scheme. But two days before Britain declared war on Germany, 350 individuals, some of whom were foreigners and had come under suspicion, were arrested and sent to an internment camp.

Enemy aliens were placed into three categories.

Individuals who displayed obvious sympathy toward Nazi ideology, who had been German army officers, or who had knowledge of munitions were consigned to category A and subjected to immediate arrest and internment.

Those who posed no serious threat to Britain but who raised concerns were assigned to category B, which forbade them from travelling more than a few kilometers from their homes.

Refugees from Nazi persecution were dumped into category C, which permitted them to continue living in Britain with the proviso that they would abide by a strict midnight curfew.

Churchill, fearing a German invasion, tightened the rules and decided that all male enemy aliens between the ages of 16 to 60 should be interned in special camps. Adolf Hitler, the Nazi chancellor, reacted to the news with glee, proclaiming that “the enemies of Germany are now the enemies of Britain too.”

The detainees at Camp Hutchison were a star-studded lot.

Curt Sluzewski was a Berlin lawyer who had practised international law. Max Grunhut was a former professor of law at Bonn University and Oxford University. Otto Haas-Heye was a fashion designer. Philo Hauser was a movie director who would appear in two Hollywood films — The Guns of Navarone and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much. Karl Franck was an architect who would change the silhouette of British cities. Rudolf Kastner had been a newspaper music critic.

Parkin expresses surprise that they were treated as enemies.

In a reference to Camp Hutchison, he writes, “It was as if a tsunami had deposited a crowd of Europe’s prominent men onto this obscure patch of grass in the middle of the Irish Sea.” That they were interned highlighted “the preposterousness” of Britain’s policy, he adds.

Fleischmann himself was released on November 26, 1941 after 18 months of incarceration. While he was granted freedom, scores of other internees remained imprisoned in camps.

Camp Hutchison itself was closed in August 1945, three months after Germany’s unconditional surrender.

Fleischmann returned to Germany as a British government translator, after which he studied at the Royal College of Art. He would become a professional artist whose work would be exhibited around the world.

In summing up this footnote of the war, Parkin condemns it as a “perversion,” particularly in light of the fact that many of the internees joined the British army upon their release and some participated in the 1944 Normandy landings.

They contributed much to Britain after the war. Max Perutz was a Nobel Prize winner. Peter Gellhorn was a conductor. Norbert Brainin, a violinist, was a founding member of the Amadeus Quartet.

Still others established key art galleries and theaters and were prominent in graphic design, advertising and publishing.

These were among the men who had been treated as enemy aliens.