The roads of southern Israel were death traps for motorists on October 7, 2023, when roughly 1,200 Israelis and foreigners were murdered by hordes of Hamas and Islamic Jihad terrorists who had invaded the country.

In an unprecedented rampage that summoned up dark and unspeakable memories of the Holocaust, heavily-armed gunmen in pickup trucks and on motorcycles slaughtered civilians at a music festival, on roads and on kibbutzim.

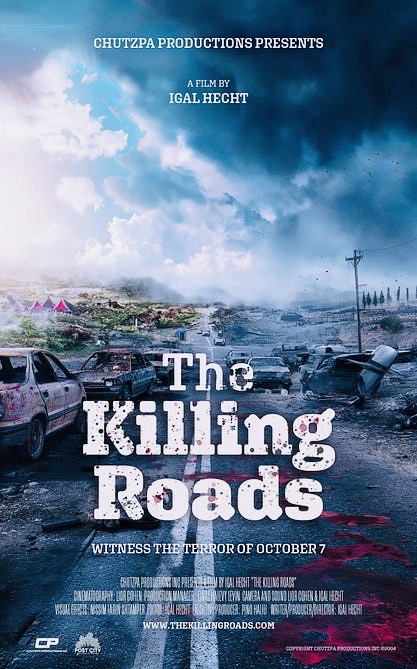

These catastrophic events are viscerally documented by Israeli Canadian filmmaker Igal Hecht in his harrowing two-hour movie, The Killing Roads. Graphic and clinical in substance and tone, it arouses dread, shock, indignation, anger and rage.

A significant proportion of his footage is searingly raw. It unfolds in real time, having been distilled from the video and cell phone clips of the terrorists and their victims. These images endow the film with a rare immediacy that captivates viewers from the very outset.

Hecht is at the center of it all. He drives along the roads that degenerated into killing fields, stopping here and there. And he interviews survivors of that massacre, the worst in Israel’s history. He aptly describes these roads as a “canvas of chaos” that spawned “unimaginable terror.”

Although he is appalled by what happened, he maintains his composure and serves as a reliable guide.

Hecht focuses his attention on two roads in southwestern Israel, 232 and 34, where scores of people in cars and in roadside bomb shelters were cold-bloodedly killed by terrorists. Their bruised, battered and bloodied bodies were later found piled up in shelters, or inside or next to their vehicles, many of which had been set ablaze by the perpetrators. In a few cases, the corpses had been burned to a crisp.

Hecht’s grim, gut-wrenching footage reveals the sheer barbarity of these attacks.

More than 300 of the victims were heartlessly gunned down at the Nova music festival amid a barrage of Palestinian rockets from the Gaza Strip. Festival participants who fled and could not make it to their vehicles were ruthlessly massacred on the grounds, or brutally raped before they were riddled with bullets. Some of the festival goers were pushed into the back of pickup trucks and taken to Gaza as hostages.

At nearby kibbutz Alumim, two young women were chased by terrorists before they were fatally shot. This horrific scene was photographed by the terrorists.

Much of the film’s power is derived from interviews Hecht conducts with traumatized survivors, though some are repetitious and could have been cut for the sake of brevity.

Moshe Weitzman, an ambulance driver who saved about 20 people in distress, recalls his experiences. The wife of a slain cyclist returns to the place on the side of a road where he was killed by terrorists. A mother remembers speaking to her son before he was murdered at the music festival. A woman named Yael Yogev vividly describes her flight from terror. Lee Sasi, a foreigner consumed by fear and confusion, looked up at the sky, saw rockets and initially thought they were fireworks. Another participant, Maya Parizer, says she waited for hours until help arrived.

Israeli troops finally came to their rescue, but the carnage was already a fait accompli. Hecht intentionally omits the political and logistical implications of October 7 from his narrative. He declines to mention the Israeli government’s responsibility for the massive intelligence failure and the army’s and air force’s relatively slow response.

In closing, Hecht acknowledges that the “horrors” of that day are “etched” into his soul and voices sadness that the post-Holocaust promise of “never again” has been shattered.

The Killing Roads is a strong and jolting reminder that October 7 will live in infamy in the annals of Israeli and Jewish history.