The title of Efraim Shmueli’s book, The Last Generation of Jews in Poland (Academic Studies Press), is a little misleading.

Shmueli, a Polish Jew born in Lodz in 1908, focuses on the storied Jewish community of Poland during the 1920s, when it was home to 3.3 million Jews, representing nine percent of its population. It was virtually wiped out by the Nazis in only six years.

Jews returned to Poland after the Holocaust, but the communist regime’s antisemitic campaign in 1967 and 1968 resulted in the departure of upwards of 20,000 Jews, leaving only a remnant of Jews.

Since then, however, the Jewish community has grown to some extent, though it is only a very pale imitation of its former self. Contrary to the book’s title, neither the fascists nor the communists succeeded in rendering Poland free of Jews.

Shmueli, who died in 1988, left Poland in 1928. He studied at the Jewish Theological Seminary and Friedrich Wilhelm University in Breslau and then spent an interlude at the University of Frankfurt, where Paul Tillich and Martin Buber were among his professors. He wrote his PhD dissertation on Hegel’s concept of individuality.

Immigrating to Palestine in 1933, he settled in Haifa and launched his teaching career in local high schools and at Haifa College, the precursor of Haifa University. From 1967 to 1977, he was a professor of philosophy at Cleveland State University. During this period, he lectured in the U.S., Canada, Israel and Latin America and wrote a succession of books about Jewish history, culture and philosophy.

In the volume under review, he draws a vivid portrait of Poland’s Jewish community in the 1920s.

As he strongly suggests in chapter one, Poland in the first quarter of the 20th century was rather backwards: “I was born into certain conditions of health care when women still died at childbirth and infants often did not survive their first year. Scant medical knowledge, filth and poor infant nutrition took their toll…”

The insular chassidic community into which he was born sought medical advice from rebbes rather than from physicians, he adds. During his upbringing, he frequented two Chassidic centers near Lodz, Aleksander and Zdunska Wola, both of which were destroyed by Nazi hordes during the Holocaust.

Jews and Poles, though living side by side, inhabited two separate solitudes in prewar Poland. Yet they influenced each other and were committed to the same national cause. Adam Mickiewicz, the great bard, hailed from a Frankist family on his mother’s side. Berek Joselewicz fought for Polish independence during the Kosciusko uprising in 1794. His son, Joseph, participated in the Polish revolt of 1831.

“Polish poets exercised tremendous influence on young Jewish men and women,” writes Shmueli. “They strengthened our yearning for national freedom, love of our homeland, defiance at the suffering inflicted on a persecuted nation.”

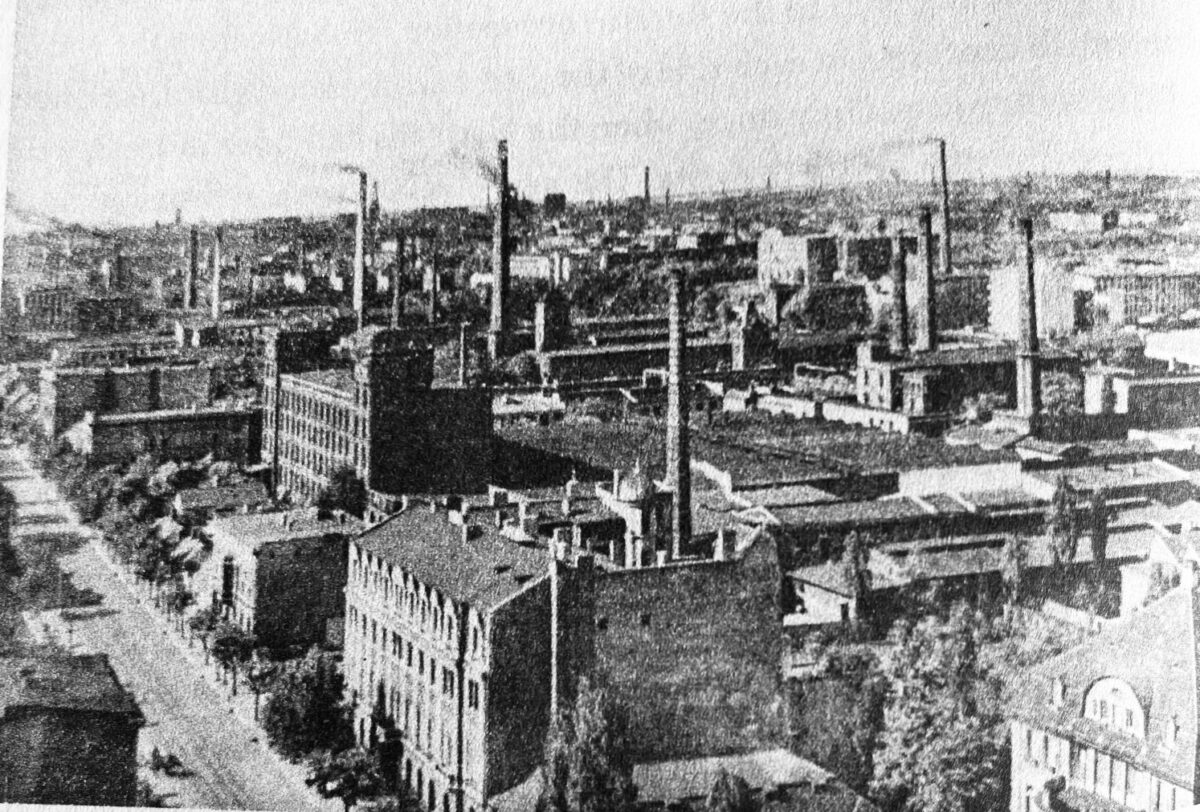

Lodz, his hometown, was the Manchester of Poland, the center of its textile industry. Comprising one-third of its residents, Jews were a key factor in Lodz’s development, with 43 percent of Jewish laborers working in industry and the rest in trade, services and transport.

During the German occupation, Jews in the Nazi ghetto survived until the summer of 1944. They did not mount a rebellion because they had no arms and contacts with the outside world, he says.

The leadership of the Jewish community during the inter-war period was wrested by Zionists from assimilationists, he claims. One of the foremost Zionist figures in Lodz, Yitzhak Gruenbaum, was a newspaper editor and politician who served in the Sejm, the Polish parliament. As the 1930s wore on, he settled in Palestine.

As Shmueli points out, the rebirth of Poland in 1918 was accompanied by pogroms in Lvov, Pinsk and Krakow. And in 1919, high-ranking Jewish officers were removed from the Polish army on the grounds that they were untrustworthy.

With Jozef Pilsudski’s rise to power following a coup in 1926, antisemitism waned. But in 1934, Poland reneged on its 1919 pledge to honor the rights of minorities. And in the wake of Pilsudski’s death in 1935, Jews felt increasingly isolated. “Only here and there did they find allies among the liberal Polish intelligentsia and in the socialist ranks,” he says.

He admits that many Jews sneered at Poles prior to 1918. As he frankly puts it, “Most Jews before the establishment of the Polish state viewed the Pole as synonymous with physical labor, drunkenness, prostitution, theft and murder. Passing by their churches, a Jew would spit … These goyim were held to be idol worshippers. Altogether in those days, the prestige of the Poles was very low not only among Jews, but also among … Russians and Germans. Only after the reestablishment of Poland’s sovereignty did we come to see that they too were human beings, but also that it was they who now has the power to harm and destroy us.”

Shmueli waxes nostalgic about Aleksander and Zdunska Wola.

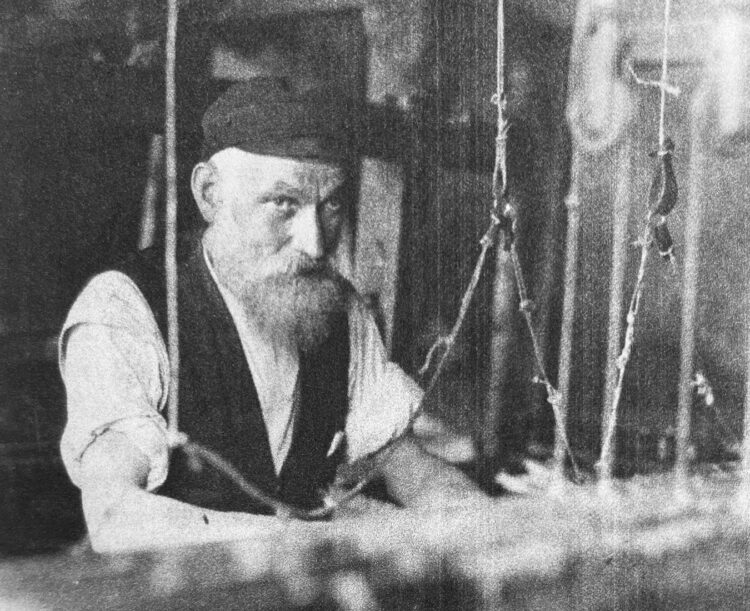

Aleksander, a town of 8,000 founded by German weavers in the first half of the 19th century, was composed mostly of ethnic Germans, 3,000 Jews and a smaller minority of Poles. The population of Zdunska Wola, population 30,000, was evenly divided between Poles, Jews and Germans.

One of its native sons, Maximillian Kolbe, was a Polish priest who, while incarcerated in Auschwitz-Birkenau, gave up his own life to save a fellow Pole. Pope John Paul II, a Pole, hailed him as a saint, but Kolbe was antagonistic to Jews.

Shmueli returned Poland on a visit in 1982 after a nearly 50-year absence. What he found was a vastly truncated Jewish community of old, ill and disabled “vestiges,” some leftists, or some crypto Jews “concealing their origins.” His appraisal is unduly harsh, but it is probably rooted in his implicit comparison between the Jewish present and the past.

He believes that Poland has been changed by major transformations. It has segued from an agricultural to a predominately industrialized nation. It is now ethnically homogeneous, with nearly all its minorities gone, the dream of prewar right-wing nationalists. It is far more Catholic than before World War II. Poles are better educated than at any time in Poland’s history.

Despite the virtual absence of Jews, antisemitism is still “a distinctive hallmark” in Poland. “The image of the monstrous Jew inculcated by the Church, by Nazism and Communism is still operative, now rolled together into the modern antisemitic version, mainly called anti-Zionism and anti-State of Israel.”

Shmueli’s observations may have been true four decades ago, when Poland was a client state of the Soviet Union. But how accurate they would be in contemporary Poland is debatable.