The South Beach enclave of Miami Beach was home to a vibrant community of Jewish retirees and Holocaust survivors from the 1960s to the 1970s. Resembling a transplanted shtetl, it was mainly populated by former garment workers from New York City who were lured there by the warm weather and the relatively low cost of accommodation. Today, it seems like a lost world.

The Last Resort, a fascinating documentary by Dennis Scholl and Kareem Tabsch to be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival on May 6 and May 7, chronicles this short-lived period within the framework of Miami Beach’s history.

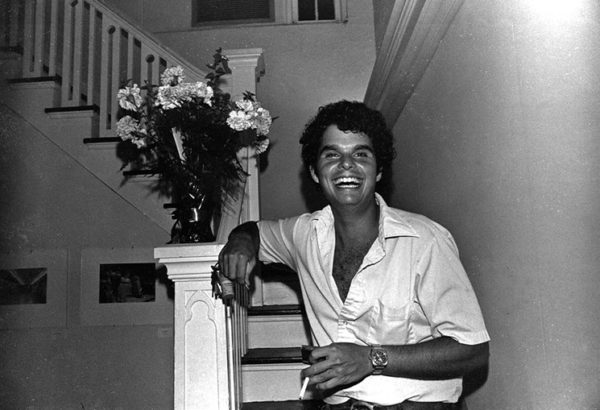

The images in it are the work of two Miami-based Jewish photographers, Andy Sweet and Gary Monroe, who launched a decade-long project in the 1970s to document this unusual phenomenon.

Founded as a resort in the 1920s, Miami Beach catered at first to only Christians. Jews were definitely not welcomed, even though a Jewish family owned one of its finest seafood restaurants, Joe’s Stone Crab, founded in 1913. When tourism rebounded after World War II, some Jews who had been stationed in Miami Beach as soldiers returned on a permanent basis. With the introduction of air conditioning, the population grew. In 1949, the city banned the notorious “gentile clientele” signs in front of hotels.

Starting in the 1960s, retired Jews from northern states began arriving in Miami Beach in droves. Usually decamping at affordable Art Deco hotels in South Beach, they spent their waking hours relaxing and socializing in the sun. Known as “porch sitters,” they frequented iconic Jewish delis like Wolfie’s and Rascal House. Holocaust survivors could often be found in Loomis Park, discussing the issues of the day in Polish-accented Yiddish.

South Beach, in short, was a kind of retirement village.

Sweet, the scion of an old and established Miami Beach family, was intrigued by these retirees. Sweet, described as a “storyteller with a camera,” took thousands of photographs of them. Saturated in bright colors, they possess a great sense of composition as well as presence and energy. His colleague, Monroe, worked in black and white and tended to be more formal. Together, they compiled an unrivalled photographic record of South Beach.

By the end of the 1970s, the scene had changed.

The retirees were dying off, and minyans were increasingly difficult to assemble. The cost of living rose beyond their means and rents rocketed following the renovation of the Art Deco hotels. Violent crime accompanied the arrival of thousands of Cuban refugees in the 1980 Mariel boatlift. South Beach’s Jewish residents could neither adjust to this criminal element, nor to the influx of drug dealers from South America. In a still unsolved crime, Sweet, not yet 30, was murdered in 1982. Monroe continued documenting South Beach, for a while at least, after his death.

With gay men replacing Jewish retirees, South Beach’s demographics underwent a sea change. These days, it is a very different place both in terms of population and scenery.

Sweet’s photographs, having been digitized and preserved, keep old memories alive.